After years as a manager, Hans Versnel went into the consulting business and soon found that the most tedious problems in organizations are almost always people problems. It's either the match between people and their work, or the match between people and people. In the year 2000, he started measuring what drives people and groups. "It is really awesome," he says. "It explains so much, and it makes you realize how different we all are. I always thought people were different, but once I started measuring… The real trick, however, is to accept those differences and make them productive. Diversity has much more value than I initially thought."

When did you last seriously examine your management style and the organizational structure of your company? With the workplace environment rapidly evolving, placing increasing emphasis on problem-solving and creativity, is the productivity of your staff being adversely affected by a traditional management approach? At the deepest level, management is a straight choice between trust and fear. Organizational culture and management style fracture into those who trust employees and allow them the discretion to act flexibly and responsibly, and those who exercise control for fear of the poor outcomes that the quality of employee judgments and attitudes might bring. It is my contention that neither approach alone is sufficient. To get the most from your staff requires a nuanced combination of the two, implemented by department, job function and sometimes even tailored to the individual employee.

After a little philosophical digging, it becomes clear that the two schools of management rehash an 18th century dispute between so-called consequentialists and non-consequentialists on the question “what is good ethical behavior?” Early English liberals like Jeremy Bentham believed that ‘good’ must be judged from the effects of behavior. In contrast, the Prussian, Immanuel Kant, argued that it is impossible to foresee the full effect of our actions and therefore we must look at the intentions behind those actions. Can you, he asked, really judge a person who caused an avalanche simply because a single stone slipped from under his shoe? The implications of these competing philosophies are much greater than you might expect, especially when it comes to management and organization. The concept of full responsibility drives some bosses, notably in English-speaking nations, to exert extreme degrees of control because they perceive the liabilities to be so huge. It is this sense of responsibility that gives these same bosses the feeling that they are entitled to a large share of profits in times of success. However, in complex organizations, as exemplified by the science and technology sectors, there are down sides to the fear-driven responsibility model. It can easily become impossible to fully control employees who are specialists or must cope with ever-changing circumstances. In my work as an organization analyst, I see a lot of employee frustration caused by rules, regulations, checklists and reports that are perceived as irrelevant or simply do not make sense.

It is natural that managers want their employees to be accountable for their actions, but compliance systems that make people feel that they are being treated like morons can be expensive for their employers. “Am I not allowed to think for myself?” is the typical reaction. “OK, then, you can solve the problems!” Broadly speaking, and in my experience, management practice follows the ancient philosophical split: the fear–compliance model tends to be favored by English-speaking nations, while a trust and responsibility approach is preferred in mainland Europe. Of course, implementation is not black and white. For example, in Europe, the finance industry utilizes increased compliance while in the UK and US, modern high-tech businesses benefit from fully engaging the skills of their specialist employees. Take Apple, Google, or eBay, for instance. Steve Jobs focused on ensuring that his staff knew what they were doing, and why – traditionally the Northern European model. In this system, managers spend considerable amounts of time discussing goals, roles and strategy, to ensure that their employees are engaged in their work. They want staff to be able to cope with all kinds of situations, embedded within a shared set of beliefs. The unwritten rule is to always explain goals and responsibilities, and to only talk about ‘how’ when asked. It’s an approach that was developed in Germany, contrary to the popular view of the country elsewhere. Indeed, while it may not be a popular subject, you can draw parallels to the relatively small force that took over much of Europe in the early 1940s; the German army was flexible and agile because it gave discretionary power to low-ranking but well-educated officers. Going back to the example of the European finance industry, the more machine-like the organization, the better the compliance model fits. If inputs, processes and outputs can be standardized, then such a model can be superb. But, in general, this is not the way that the world is developing. Work that can be standardized can often be mechanized or computerized; the tasks left to humans require insight, flexibility, and the ability to perform in changing circumstances. That’s the essence of work in the 21st century and it seems to match increased employee trust and responsibility perfectly. This may explain why, per capita, northern Europeans make about the same amount of money as their American counterparts, but Americans have to work 40 percent longer. Does this mean that there is no place for command and control management? Well, not quite.

Whether you’re a team leader in a small European toxicology lab or a director at a giant American measurement solutions provider, understanding and managing the motivation of your staff is the key to success.

As developers of systems that measure motivational patterns, or drives, my colleague Machiel Koppenol and I have collected data for more than 100,000 people worldwide. Our instruments are used to gain insight that can help improve leadership and team performance. With RealDrives (see ‘What Drives Us?’) we identified factors that help determine the balance between people, work and management styles. We distinguish between six drives, using the categorization developed by Clare W. Graves in the 1970s, namely the drive:

- to preserve traditions

- for power

- for certainty

- to connect to others

- for progress

- to understand

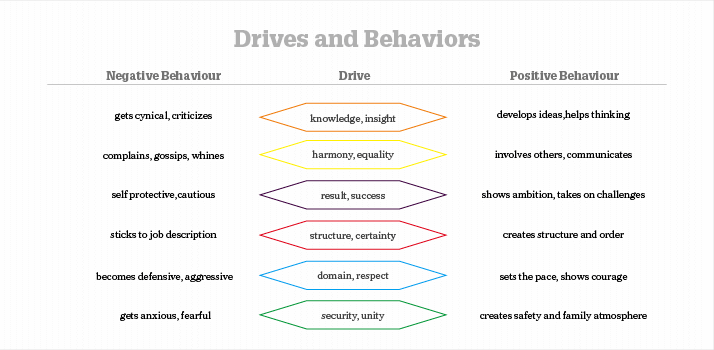

Failure to recognize the driving force behind your employees results in a loss of productivity. In one study, we measured the drive patterns of 1,100 sales people to find out which profiles worked best in different sales contexts: some did simple commodity sales, some sold complex solutions, and some sold within a relationship-oriented market. We compared the drive patterns of individuals in different sales categories with their results. For each group, successful patterns were observed but we also identified a number of underperforming patterns. These individuals had the ‘right’ drive pattern but they sold 40% less than their colleagues. When we drilled down to figure out why, we discovered that almost every underperformer had a boss of the wrong type in terms of the ‘how or what’ dimension. Every drive has a positive and a negative behavioral style (see ‘Drives and Behaviors’). If a person is managed well, positive behavior results. If managed badly, creativity turns into cynicism, responsibility becomes “I just do what is in my job description”, and so on. This is not a minor consideration. For a large company, the cost of negative behavior throughout the entire organization can be immense. And for a small company, it can be a matter of life and death. So, how can you as a manager promote positive behavior? First, don’t assume that extra force will help. In reality it is much more likely to make things worse. Second, start to trust people more and encourage a greater degree of ownership. And last, but certainly not least, find out what drives each of your staff – which means understanding what they really find important.

More information about RealDrives.