Like it or not, the workplace is constantly changing. Usually discussions about change focus on changing things – processes, structures, formats, and so on. As interesting as those topics are, there is plenty of literature on how to effectively lead, manage, or adapt to such change. Instead, I want to discuss a subject that is rather more personal: how to change ourselves. As we grow and develop (both personally and professionally), it’s natural for us to identify areas that we want to improve – or change. Yet, despite a strong desire to grow and adapt, there are often aspects of personal change that we are unable to make or to sustain. Why is this? According to Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey, Harvard professors and authors of the book “Immunity to Change” (1), there is a very good reason for our resistance: a psychological protection mechanism. Here, I will interweave an overview of Kegan and Lahey’s approach to overcoming our natural resistance to change with my personal coaching experiences of trying to help clients attain their highest potential through change.

Some people don’t have to think long to know exactly what they want to change about themselves or what they need to change to be successful. For others, it may take some thought. Constructive feedback about your performance at work can serve as a good starting point and families and partners can also supply ‘critical’ information on where we could improve. If you don’t receive any kind of feedback, I encourage you to seek it out. Identify the peers or colleagues whose perception of you really matters and ask them. Finding out areas where others perceive you positively can be quite validating and, on the other hand, discovering those areas where you are negatively perceived can be a strong motivator for change. When choosing an aspect of yourself to improve, remember to identify a behavior rather than an outcome. You may want to be more influential, reach or exceed targets, or increase employee engagement – all worthy goals. To achieve these, identify which behaviors you must improve. Perhaps you need to get better at dealing with conflict, or speak up more at meetings, or become a better listener. Notice that these change goals are stated in the positive. If you have a goal to stop doing something or to not behave in a certain way, restate it in the affirmative. For example, if you want to stop interrupting people when they talk, you could say you want to let people finish talking before you interject. The most important thing is that you have to really want to make the change.

Once you have selected behaviors that you truly want to change, write down a list of the things that you currently do or don’t do in relation to those behaviors. For example, if you chose to improve how you deal with conflict, you might write down that typically you sugar-coat your words, don’t address issues, or avoid certain people. Give this some thought and perhaps observe yourself for a few days. Better yet, tap into those who gave you the initial feedback or enlist the help of a trusted friend or colleague to observe you. Make the list as extensive as you can. Up to this point, the process may sound somewhat familiar. But this is where things take an unexpected turn. Typically, improvement plans suggest that you get feedback, identify an improvement goal, get tips on what to do, and start practicing those new behaviors. If you need to stop interrupting people, you are usually advised to take a few minutes before a meeting to remind yourself and to ask a colleague to observe you or give certain signals to warn you when you stray. When you are merely trying to break a bad habit, this approach might work; however, you may find that you repeatedly slip back to your old ways, which could mean that there is something else lurking in the background. If you have been unsuccessful in changing a behavior by following a new tip sheet with sheer hard work and determination, another tip sheet and more hard work and determination are unlikely to make a difference. Remember that Albert Einstein once said that insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. I challenge you to take this next step.

Actually, the next step is a step back. We’re not going to tackle new behaviors at this stage; in fact, we’re not even going to think about working on the original goal at all. Instead, we will try to uncover a goal or commitment that you didn’t even know you had – a so-called “hidden commitment”. Hidden commitments are driven by emotions – our worries, concerns, or fears that cause us to take protective measures. To get at your hidden commitments, go back to your “do/don’t do” list. For each of the behaviors you’ve listed, such as a tendency to sugar-coat your words, imagine doing the opposite and try to write down the emotions that emerge. Don’t make this an academic exercise; instead, really imagine yourself in these situations and allow yourself to experience and focus on the most negative, emotionally-charged reactions that could result. For example, you may have listed that “I often interject when other people are talking”. Now, imagine the opposite behavior: always allowing people to finish their point before you speak. How does it make you feel? It may produce a strong fear of appearing stupid or uninformed, raise concerns that you will have no say in decision-making, make you appear weak or unsuited for promotion, or that you will somehow lose control of the discussion. If you would feel embarrassed to let other people see this list of fears or worries, then you are on the right track!

The next step is to restate these fears as commitments. The key is to retain the fear or worry within the commitment; for the example above it might state “I am committed to not appearing weak” or “I am committed to not losing control”. These commitments should read like some form of self-protection rather than the statement of a noble goal. Once you have written out these clear personal commitments, go back and look at the do/don’t do behaviors you have listed. The commitments should now seem like ways of overcoming the fears and worries you’ve identified. Kegan and Lahey compare these hidden commitments to an immune system. Like the real immune system, the hidden commitments are actually working actively in the background to protect you, and you need to disable them to generate real change. The key to overcoming this form of immunity is to examine and question its underlying assumptions. Ask yourself what assumptions make those hidden commitments feel so necessary. In the above example, your assumptions may be that you will appear weak or stupid, or that you will lose people’s respect, if you listen more than you talk. Each hidden commitment generates numerous assumptions about how you will feel, how others will react, or just about the world in general. You may find that the assumptions don’t all make sense from an intellectual point of view, or discover that you believe them to be absolute truth. Either reaction is okay. You may notice that your assumptions put boundaries around you, and that if you cross those boundaries you enter ‘unsafe’ territory.

The next step is to test and challenge your assumptions. As analytical scientists, this stage may appeal to you. Try to design and execute experiments that can invalidate or refine your assumptions in a way that opens up new, safe territory for you to function in. It is important that these experiments do not actively attempt to directly address your original objective (changing your behavior), rather they should only seek to discover flaws within your own assumptions. The key is to gather information from our behavioral changes that lead to changes in our mindset. We must believe and think differently to sustain behavioral changes. Use the SMART acronym to guide you as you design your tests.

S-M: your experiment should be both safe and modest. Attempt doing (or not doing) something small that carries low risk but that will still give you information to assess one of your assumptions.

A: Choose something that is easily actionable in a normal day.

R-T: Take a research stance (not a self-improvement stance) and test your assumption. The point is to collect data, not try out behaviors necessary to your original goal.

For example, let’s say “John” assumes that he will appear stupid or uninformed if he talks less and listens more. John must first ask himself what small changes he can make that would give him valuable information about his assumption. John planned to try a small change in an upcoming discussion with a trusted colleague who is facing a challenging situation and wants to talk it over. First, John planned what he would do and how he would do it. He decided to adopt a position of curiosity, to hold back from interrupting, and to ask questions rather than give advice. He felt that it would be easier to try this unfamiliar approach one-on-one with someone he trusted during a short conversation. He planned to collect data on how he himself felt and to record what his colleague actually said and did. After the conversation, John noted that it was hard to keep quiet at first and then it got easier. He also realized he learned more about the situation by being quiet. He noted that his colleague was quiet at first and then began to talk more and responded thoughtfully to the questions John posed. At the end of the discussion the colleague expressed how helpful John was and that he appreciated John taking the time to help him sort through this challenge.

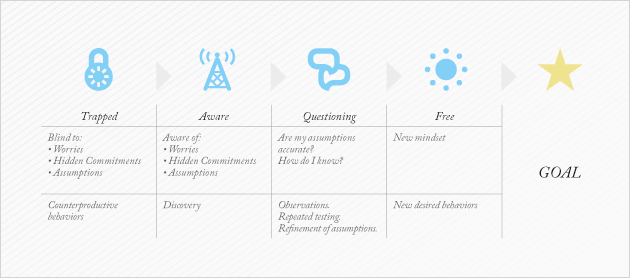

John’s interpretation of this initial experiment was that talking less was actually less taxing and stressful for himself and that he provided value without dominating the conversation. Since this was a trusted colleague, John could further explore his assumption by telling his colleague about his assumption and asking him whether John appeared uninformed by taking this approach. These data could serve to modify John’s assumption or to create new ones. One single test is unlikely to be conclusive or create a major breakthrough. The point is to keep refining your data and expanding your boundaries. John may now decide to try this approach in a more important meeting and ask his colleague to observe and help interpret responses from others on the team. Enlisting supportive friends and colleagues can be invaluable as you continue to modify and test your assumptions. Once the assumptions no longer hold, the self-protective behaviors are no longer necessary. These steps may take some time and practice, but at some point you may find that you are no longer conscious that you are trying to interrupt your main assumptions. Use Figure 1 to help remind you of the process. Once you are unconsciously acting counter to your assumptions, you will be on your way, if not fully successful, with your original goal.

The fact is, that if you have tried repeatedly – and failed repeatedly – to change your behavior, don’t be too hard on yourself. You may actually be quite brilliant, having created an incredibly powerful psychological immune system! Examining this system carefully and testing and refining the underlying assumptions that keep you from your goal are the keys to overcoming your resistance to change. Good luck.

References

- R. Kegan and L. K. Lahey, “Immunity to Change” (Harvard Business Review Press, Boston, MA, 2009).