Bill Devorick is a Senior LIMS Consultant for CSols, Inc. where he helps clients achieve their laboratory informatics and related compliance objectives. "I enjoy applying a scientific approach to compliance and computerized system validation, and am particularly interested in team dynamics, human motivation, and mindfulness as tools for adding value to organizations". Bill has a BS in Chemistry from Lehigh University, an MS in Chemistry from San Francisco State University, and an MBA from Eastern College.

As a lab manager, how can you boost vitality, promote collaboration and engender inspiration among your staff ? Here, Bill Devorick proposes that personal mindfulness and an understanding of motivation theory will improve teamwork. Combine these to create your own ‘Maximum Lab’.

As a lab manager, how can you boost vitality, promote collaboration and engender inspiration among your staff ? Here, Gregory Weddle describes how lab design can enhance the creative process while Bill Devorick proposes that personal mindfulness and an understanding of motivation theory will improve teamwork. Combine these to create your own ‘Maximum Lab’.

Analytical laboratories can be stressful places. Management wants steady output at lowered cost. Production customers require results to release product. Quality assurance demands compliance with high standards and strict documentation. And the complexities of science and instrumentation do not always yield to analyst intentions. Almost any analytical laboratory can improve in terms of motivation, teamwork, vitality and fun. But how can an engaged manager bring these changes about? I suggest ‘striving with intention’ as one way, by which I mean applying motivation theory in a mindful fashion. Here, I shall introduce the concept of motivation and describe mindfulness, and explore how they can be used together to improve the working dynamic in the laboratory and the overall success of the team.

The process starts with you, the manager. To have a positive impact on laboratory dynamics, you must first care for yourself and want to improve your personal awareness; you must pay mindful attention to your experiences, to the realities of the environment, and to improving your analytical and critical thinking abilities. You must also care for your team. And you must have concrete tactics.

In a review of decades of motivation research, Vallerand (1) concludes that the extent of motivation (or passion) is determined by a combination of factors: the person, the job-at-hand, and the social setting. Motivation theory in the context of mindful attention, provides a solid basis for problem-solving that is relevant to the analytical laboratory.

Motivation theory

The history of motivation theory is storied. Reeve (2) developed the concept that there were three ‘grand theories’ in the early study of motivation. The first, the theory of will, dates back to Socrates, Plato and Aristotle. The will intervenes in decisions related to wants and needs, guiding the decision to either do or not do something. The second, the theory of instinct, has its basis in the ideas of Charles Darwin. In this view, biologically-based instincts, like those for food and comfort, direct behavior. The third, the theory of drive, has a focus on urges and their fulfillment, and found a supporter in Sigmund Freud. Interesting as they are, these grand theories have been relegated to the back-burner as they are insufficient to address the practical realities of motivation. A wealth of new theories arose in the second half of the 20th century that provided insights applicable to the workplace, such as achievement motivation theory, goal setting, flow theory and self-determination theory (SDT). To illustrate the practical utility of these concepts, I will give a synopsis of each theory and an example of its application.Achievement motivation

Having both classic and contemporary interpretations (3), achievement motivation research shows that people in teams act with greater intention when they perceive their role as central to success (4). Similarly, each individual’s orientation toward success, for example expecting to succeed or expecting to fail, influences his or her choice of tasks. So – and this is a common theme and starting place – careful consideration of each individual in the team is critical. Know yourself and your analytical team members, and your tasks and task complexity, then consider the team makeup and the perspective of each team-member on the tasks at hand.Goal setting

A ubiquitous activity in businesses today, people seem to better accomplish tasks when they have goals and when the goals and tasks are properly challenging for each individual. Watch out for overly-ambitious goals, as these may indicate, counter-intuitively, a fear of failure.Flow theory

Getting in the flow of activities and maintaining focus is an experience that most analytical scientists have while working in an area of competence on just the right challenge. Notice flow and energy levels in the laboratory, as these provide clues for successful adjustments.Self-Determination Theory

With the advent of the multiplicity of theories, a need for integration emerged. SDT seeks to integrate a variety of perspectives; Deci and Ryan (5) describe it as a macro-theory. In brief, STD posits two primary and two secondary categories of motivation. The primary categories are autonomous and controlled; autonomous motivation has the characteristic of ‘self-endorsement’ while controlled motivation is essentially extrinsic, either depending on rewards or punishments or on internalized schemas. The secondary components are relatedness and competence, highlighting the importance of knowing team member goals and individual outlooks to properly align these with the team’s challenges. Luckily, in the analytical lab there are plenty of opportunities to be challenged and to enjoy making decisions. Aligning tasks so that each team member is intrinsically motivated, appropriately challenged and in the ‘zone’, can strengthen team collaboration and bring energy to the workplace. I encourage managers to investigate motivation theory. A personal synthesis of theoretical ideas is a valuable tool for getting the best performance from yourself and your staff.Mindfulness and inspired motivation

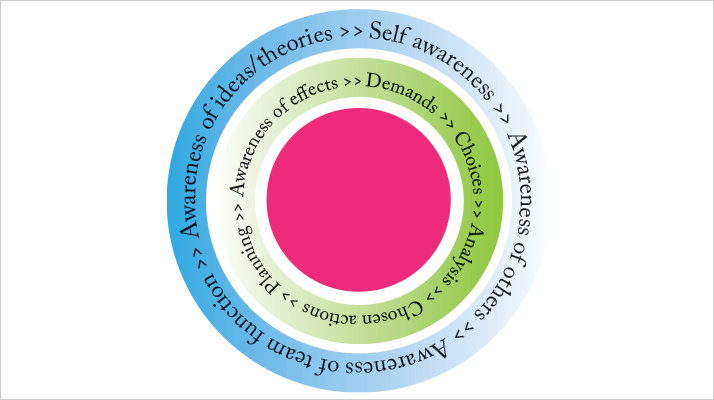

Zinn (6) describes mindfulness as ‘having to do with being in touch’. A person’s ability to improve his or her own mind, simply by attending to the mind as a functioning object in its own right, can be something of an eye-opener! This mental improvement is not just a felt sense, it also correlates to real neurological changes. Bringing active attention to the mind, that is, meditation, is the main way people develop mindfulness (see Figure 1). Direct observation of our physical experiences, feelings, and thoughts, fosters direct insight into the nature of our sense of self, releasing vitality, and supporting a stronger sense of our place in the world – and in the analytical laboratory.

The initial ‘strangeness’ of mindfulness has waned considerably in recent years. Conferences such as Wisdom 2.0 and the work of US Congressman Tim Ryan, for example, demonstrate the widespread interest in mindfulness as a way to improve health and effectiveness in the workplace and in society at large. With wide-ranging benefits chronicled in hundreds of articles, mindfulness is truly becoming a mainstream perspective and can be just the meta-skill needed to mobilize the right actions for improving the workplace.

Personal development is at the heart of mindfulness. Gaining personal understanding is the starting point and it can be introduced into teams, for example through group mindfulness training. This approach can instill a sense of community but it should be introduced on a voluntary basis, with no coercion of any kind. A casual, off-site group may be formed, spanning several departments of the workplace or multiple workplaces. A short set of four one-hour workshops, for example, can provide a starting-point.

The challenges of the analytical lab will not disappear. But with appropriate focus and attitude you and your team can perform better, with more vitality and greater enjoyment.

Quick six to improve motivation

Develop mindfulness: Explore tools/techniques to improve mental function. A good start is Zinn’s Wherever You Go, There You Are (6). Continue or start a meditation practice. Know personal limits and patterns of clear and less-than-clear thinking.

Know yourself: Observe the self. Use meditation and other tools, and know your own skills, strengths, and weaknesses. Improve competence and stay current with technical and interpersonal skills.

Know others: Discover the ‘career’ goals and skills of each individual. Work with others and maintain relatedness. Create a skills matrix. Trust each person to achieve his or her goals. Pay attention to verify progress and help out, as appropriate, to develop the competencies needed for the individual to continue to be a valuable contributor.

Know the team: Focus on the work at hand and listen to the sub-text. Pay attention to the level of confidence and expectations of each member. Consider mini-teams of two or three (for example, match a good teacher with somone lagging behind). Consider the cumulative capabilities of the team and match them to the challenge at hand. Foster communication.

Prime for success: Help others learn how to be successful. Be the one to clear obstacles or point the way forward. Appreciate the work being done. Understand the value of success, and failure. Monitor progress and make adjustments. Communicate.

Be fair and honest: Act with mindfulness and integrity. Fairness does not mean indentical treatment of each person. Be honest by relating helpful information and sharing skills, techniques, and understanding. Blend mindful awareness with analysis.

References

- Vallerand, R. J. (2012). From motivation to passion: In search of the motivational processes involved in a meaningful life. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 53(1), 42-52. Reeve, J. (2009). Understanding Motivation and Emotion (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. Elliot, A. J., & Church, M. A. (1997). A hierarchical model of approach and avoidance in achievement motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(1), 218-232. Zander A. & Forward, J (1968). Position in group, achievement motivation, and group aspirations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8(3), 282-288. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory or Human Motivation, Development, and Health. Canadian Psychotherapy, 49(3), 182-185. Zinn, J. K. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion.