If we think of supervisory transitions at all, it is usually that first big step into a “managing role.” However, as we advance and receive promotions, we continue to face significant transitions with each change in our position. Such transitions happen many times during a career and aren’t limited to “new” technical supervisors. Even those who have supervised others successfully can struggle with further advancement as their role changes. Understanding these transitions can help make them easier and more successful.

Transitions into new roles and responsibilities often mean increased compensation and prestige. Unfortunately, this entices some of us to take roles for which we are not prepared, suited, or even skilled. In fact, the technical skills that lead to promotion can also be the skills that undermine supervisory success. That’s because, as professionals in analytical science, the recognition of our skills and abilities by others (that is, getting credit for results) is important. This is true not just for advancement or for changing jobs; it is also a key factor in building our self-esteem and security. The perceived threat of losing that recognition can be strong. Therefore, we need to adjust our motivations and work values to bring us fulfillment when we manage the work of others. There are four key requirements to making a successful transition and you need to meet them all. Ask yourself:

- Am I willing to give credit to others?

- Am I motivated to help others succeed?

- Do I listen openly to others’ ideas?

- Am I interested in taking on new roles?

Your behavior in response to these questions affects your relationships, your style of communication, and how you utilize supervisory skills, such as delegation and coaching. If the lure of additional compensation, a new title, or organizational prestige is your main motivation for seeking a new position, ask and answer the four questions again. If one of your reports solves a critical problem, will you ensure that he or she gets the recognition? If staff members who report to you struggle, will you spend time helping them? If there is a problem with an analytical procedure, will you first ask your team member for input and listen carefully, or will you start by explaining your own views and expecting people to follow your approach? The latter is more efficient, but asking questions and requesting input will help your staff to grow. As you teach the people that you supervise to think through and analyze their ideas, you will also learn and perhaps discover an even better solution. Some of us are naturally suited to supervisory roles and enjoy communicating and working with others. Indeed, research into differences between managers and scientists shows distinct behavior patterns and preferences (see “Manager or Scientist?”).

That said, our preferences change with time and circumstance. I worked for a period at Los Alamos National Laboratory where, at first, I resisted taking a supervisory role. I had previous experience in managing others, when I set up an electron microscopy lab and trained new technicians, but at Los Alamos I loved my work. I was productive and I feared that supervising others would slow me down. It wasn’t until someone pointed out that I could try many more of my ideas if I managed others that I agreed to the new role – and I never regretted it. In contrast, at about the same time one of my colleagues took a senior manager position at another organization; he missed his former role so much that he returned to it after a few months, and never again applied for a management role. He did the right thing. Unfortunately, most of the individuals who make the transition and find that they regret it never go back. Both they and their employees suffer.

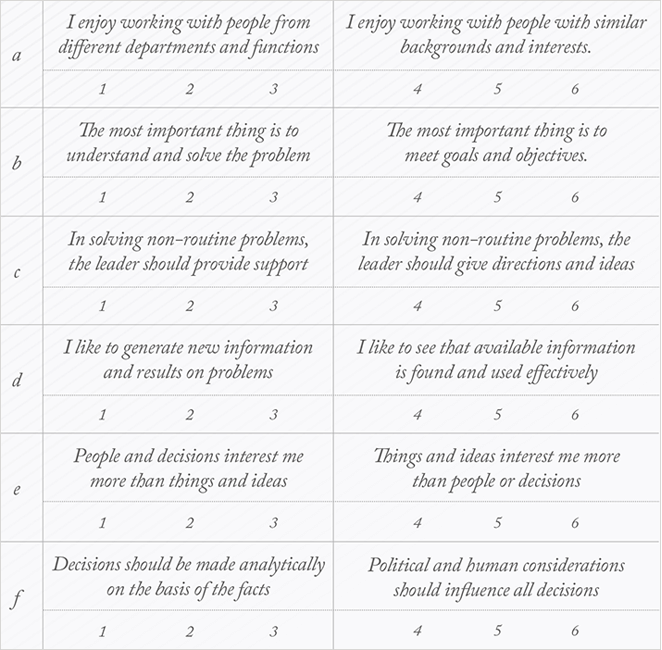

Using data from the literature and from our own experience, Gus Walker and I developed the “Manager or Scientist: Attribute Inventory” (1, 2). The inventory lists thirty statements to be rated on a scale of 1 to 6 between two preferences (there are no right and wrong answers). A selection of the statements are shown below.

The inventory includes scoring and interpreting of results. A strong profile in either direction does not preclude or imply success as a manager or scientist but suggests transition may be difficult. This is particularly true with continued advancement, as the roles of manager and scientist/technical specialist become more distinct.

The indicator has helped many people to understand some of the issues they have experienced as managers – or may face, if they become one.

It often helps to clarify internal struggles, so that they can be recognized and addressed.

Three important transitions

During career development, managers pass through transitions that reflect their knowledge and ability relative to the people that they supervise. Each of these three transitions presents new challenges; they are:- Supervising former peer(s) where your skills and experience are greater than theirs.

- Managing those whose skills and experience levels are very similar to yours.

- Leading groups with varied technical skills, including individuals who have more experience or perhaps greater and entirely different skills.

The first transition could be taking on supervision of one or more lab technicians. Typically, when a technical professional receives a first supervisory assignment, junior staff act as assistants or simple extensions of the professional, similar to relationships in universities. Initially your technical skills and experience are probably greater than those of the individual(s) you supervise. It is, in fact, this expertise that probably earned you the promotion. For many first-time supervisors, a major concern is about supervising individuals who were previously peers or may be older (or even more experienced). The key here is to have frank discussions about your new role and expectations. Listen and stay open to others’ ideas. Learn from those who have been with the organization longer and recognize their contributions. This first transition won’t take you far from your technical roots. You may be working alongside your supervisee in the lab, but this is not the case for subsequent transitions. As you advance, you will no longer be the individual best able to handle a specific technical task. In a second transition, you may be supervising people with equivalent technical capabilities. They may even have greater experience or perhaps a more advanced degree in another area. Giving up a degree of control to people that you manage can be a major challenge. The ability to handle these interactions is a key test of managerial aptitude, and delegation is important to success.

Unfortunately, more skill or experience in one area convinces some supervisors that they are superior in other skills as well. This often leads to over-direction and micromanagement, leading to a frustrated staff. It can also mean you don’t recognize special abilities in the people who report to you. For those who relied on giving close direction in their initial supervisory role, this transition can be especially difficult. One’s experience and training can create strong feelings about the best approach to a problem; however, if you continue to promote only your own solutions, your staff may resent their lack of influence. To those with knowledge beyond your own, such behavior is seen as incompetence. Instead, you should rely on the skills and abilities that they bring, and work collaboratively to generate creative solutions. Use the tools available (for example, lab notebooks and technical data) to review and assess results and procedures – even PhD scientists often do not have good experimental design skills. Protect your staff from interruptions (including your own) and guide them through meaningful review and questions. The third major type of transition occurs when you have responsibility for a large organization or must deal with interdisciplinary teams that include people who have management responsibilities themselves. Compared with the two previous transitions, you need less technical competence for this role; instead, general knowledge and the ability to manage resources and integrate and prioritize tasks are crucial. You must understand and achieve your goals by trusting and relying upon your staff and creating a motivating climate. This does not mean that you should ignore the technical work; use your ability to evaluate approaches and results and to guide progress via thoughtful questions and meaningful discussions.

Research and development managers can face each of these three transition stages multiple times in their careers. They are handled best when they are recognized and carefully considered. Failure on the part of many people to do so may explain why only 25 percent of the scientists and engineers I’ve met over the years say they have worked for an outstanding boss.

Rarely is there organizational support to help you focus on the important transitions needed for managing other professionals. At best, you will receive training in delegation, performance management, communication, and other supervisory skills; the importance of recognizing and helping with the behavioral and psychological elements of a transition is rarely considered. And yet, if we reflect upon and expect transition issues, we are better prepared to handle them.

Join her March 5 at Pittcon 2014 Short Course #139 to take the Manager or Scientist Attribute Inventory and focus on supervisory skills.

References

- E. N. Treher and A. C. Walker, “Manager or Scientist: An Attribute inventory” in The 2000 Annual: Vol 1, Training, 153-166 (Josey-Bass/Pfeiffer, San Francisco, 2000).