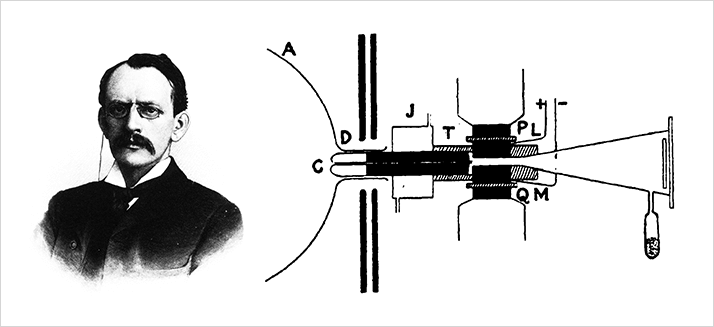

This year, we celebrated the centenary of J. J. Thomson’s publication of a monograph entitled “Rays of Positive Electricity and Their Application to Chemical Analysis”. Thomson was most definitely a visionary, but the chemical community was not quite ready to embrace the positive ray analyzer, what we now know as the mass spectrometer. However, his colleagues in the physics community saw that the instrument was critically important in the investigation of the elements and their isotopes; a concept that only became accepted in the early 1920's. Of course, much groundwork had been done by a variety of researchers prior to 1913, providing Thomson with a foundation to base his research on. Here, I examine significant developments both before and after the publication of Thomson's monograph.

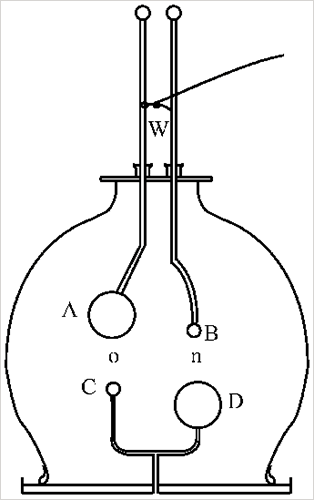

The origins of mass spectrometry began with the earliest gas discharge experiments. These were conducted in a partially evacuated glass envelope in which electrodes were inserted. At an appropriate gas pressure and voltage across the electrodes, a variety of glowing light phenomena were observed. While frequently used as an entertaining display of the curious properties of electricity, a number of serious researchers were intent on better understanding the various phenomena. Originally, only qualitative observations could be recorded; how the glow in the tube changed with pressure, nature of the gas, and magnitude of the voltage.

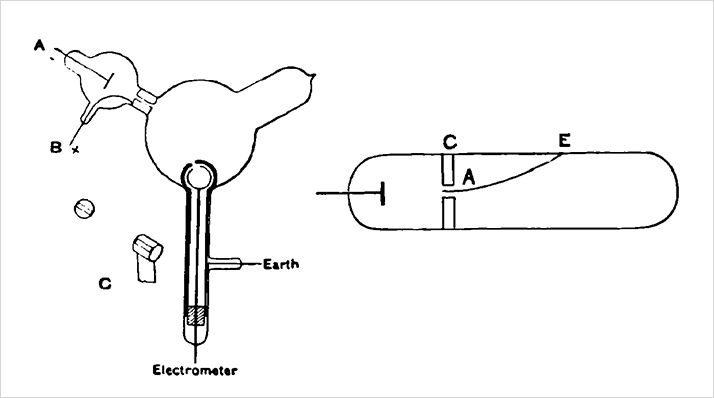

One of the earliest scientific puzzles posed by the gas discharge experiment was whether or not charged particles were involved, or only light was produced. By experimenting with magnets and additional electric fields, researchers such as Goldstein, Hertz, Lenard, Crookes, Perrin and Wien, determined that ‘corpuscles of negative electricity’, or electrons, were present. Thomson was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1906 “in recognition of the great merits of his theoretical and experimental investigations on the conduction of electricity by gases”.

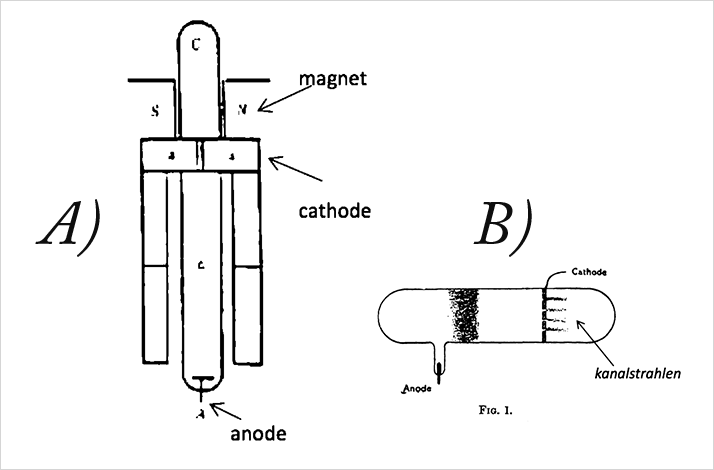

Many of the same researchers who investigated cathode rays also turned to the study of kanalstrahlen, or positively charged particles, produced in the gas discharge experiment. At first Goldstein thought they were unaffected by magnetic fields. Later Wien and Thomson showed that kanalstrahlen could be deflected if the magnetic field was strong enough.

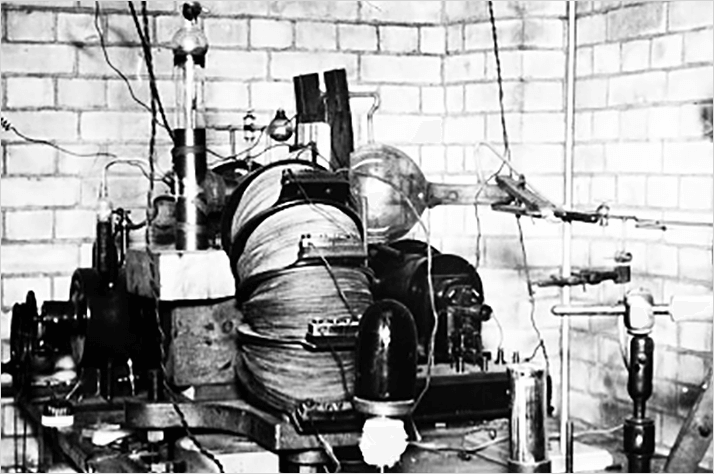

Thomson was able to obtain mass spectra of various gases and compounds with this apparatus in the early 20th century. While demonstrating proof of principle, it was not an easy tool to use, despite his advocacy of it in his 1913 monograph, “Rays of Positive Electricity and Their Application to Chemical Analysis”.

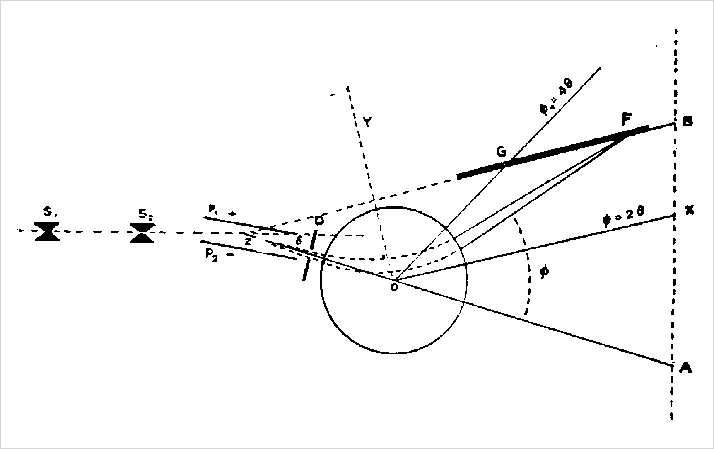

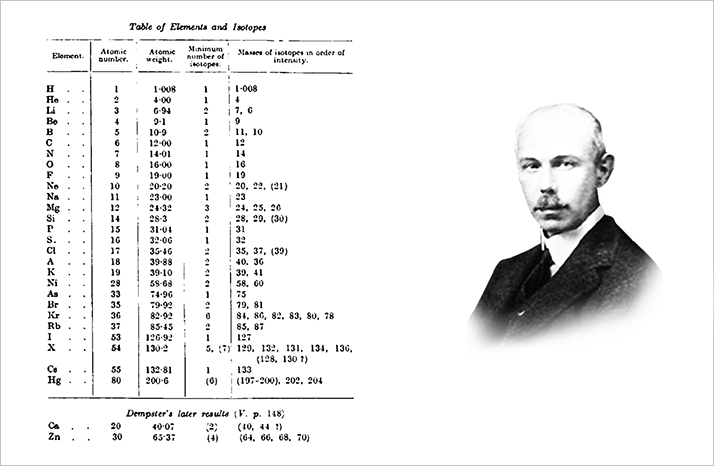

Francis W. Aston studied under Thomson and quickly realized that Thomson’s mass analyzer was limited in both resolving power and mass range. He began to develop a new mass analyzer which he would improve over several decades. He still relied on the gas discharge experiment to produce ions for analysis, but was able to obtain much better mass spectra. Aston’s work with this instrument earned him the 1922 Chemistry Nobel Prize "for his discovery, by means of his mass spectrograph, of isotopes, in a large number of non- radioactive elements, and for his enunciation of the whole-number rule"

Beginning in the early 1920s, Aston began a life-long investigation of the elements and their isotopes, determining their precise mass and relative abundance. During his career, he published almost 70 journal articles and several books on the subject. While others in Europe and America made some contributions, Aston essentially owned the field.

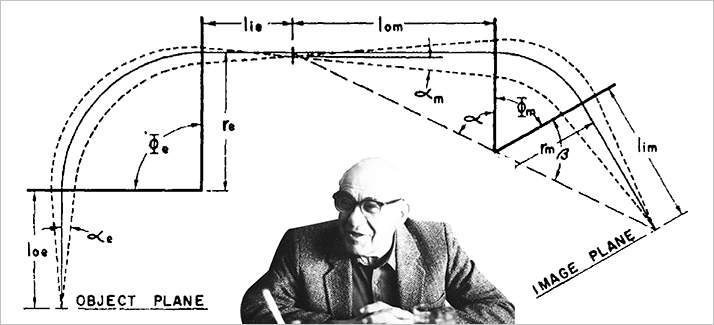

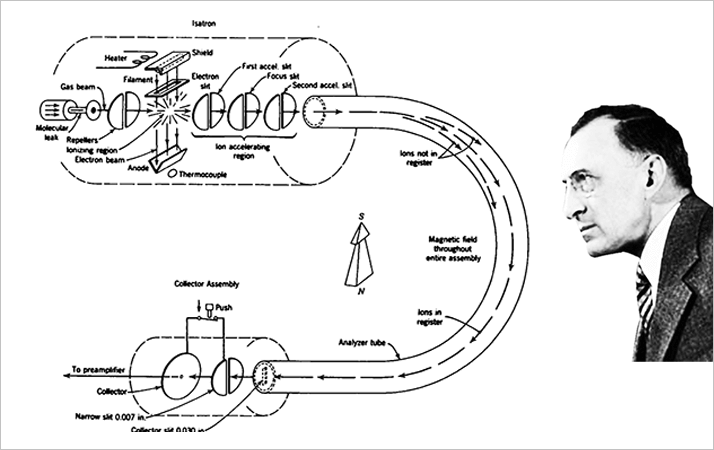

Alfred O. C. Nier, perhaps more than any other physicist, helped to spread the application of mass spectrometry in many different scientific fields. With a strong background in electrical engineering and excellent experimental skills, he specialized in creating inexpensive, reliable instruments suitable for specific applications (isotope ratio analysis, leak detection, process control, general analytical, upper atmosphere analysis, planetary atmosphere analysis, respiratory gas analysis). He gave away his instruments and expertise to colleagues both inside and outside the physics and University of Minnesota communities.

A. J. Dempster, working at the University of Chicago, built a positive ray analyzer similar to that of Thomson and he too decided that a new mass analyzer was needed. His approach, the 180° magnetic sector instrument, was operational before Aston had finished his first mass spectrograph. Dempster also abandoned the gas discharge experiment as a means of producing ions and developed an ion source to produce ‘slow canal rays’, thus simplifying the requirements for the mass analyzer.

A new generation of physicists rose to prominence in the early 1930s, among them Kenneth Bainbridge, Josef Mattauch, and Walker Bleakney. They developed more powerful instruments, refined the accuracy of measurements of the relative abundance and masses of the elements and their isotopes, and broadened the application of mass spectrometry to areas outside the realm of physics.

For more information, see “Critical Mass: A History of Mass Spectrometry”, taken from the joint ASMS-CHF Oral Histories project .