Candice Ulmer

Candice is a clinical research chemist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where she is the Project Lead and Acting Chief of the Clinical Reference Laboratory for Cancer, Kidney and Bone Disease Biomarkers. Her work focuses on the standardization of clinical measurements and the development of reference measurement procedures for chronic disease biomarkers. As an early career analytical scientist, Candice serves on various international committees and has published over 30 peer-reviewed papers.

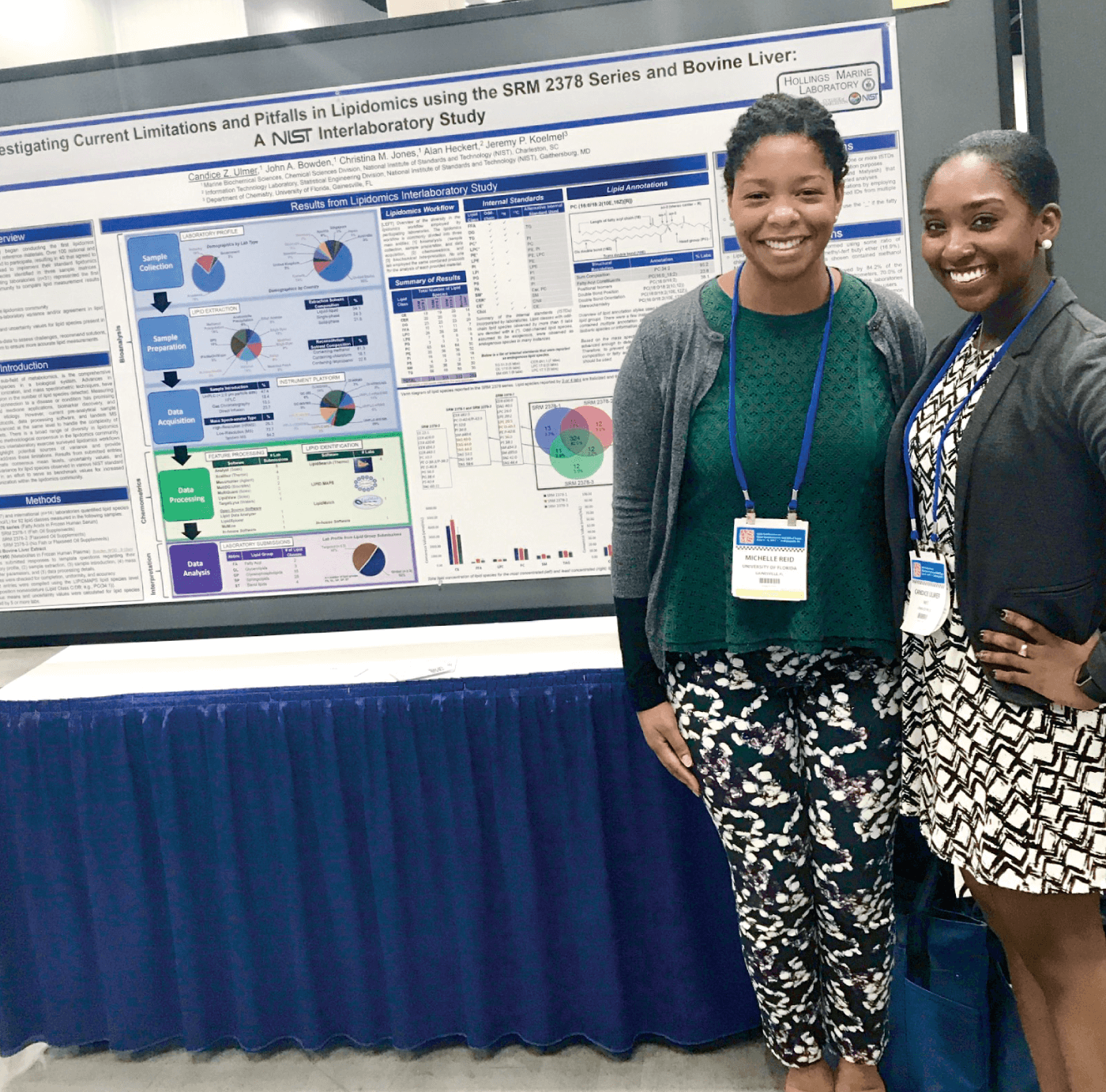

Christina Jones

Christina is a research chemist at the National Institute for Standards and Technology, where she focuses on measurement harmonization and standardization for metabolomics. She has received numerous awards as an early-career scientist and published over 25 peer-reviewed papers. As well as being a co-founder of the Coalition of Black Mass Spectrometrists, Christina is also co-founder of Facilitate 2 Motivate.

Michelle Reid

Michelle recently finished her postdoctoral fellowship at ETH Zürich, researching the systems-level view of Salmonella pathogenicity and quality assurance in MS. She is also a co-founder of the Coalition of Black Mass Spectrometrists, and is a co-chair of the Females in Mass Spectrometry Mentorship Committee.

Ulmer: A few years ago, Renã Robinson told me about her vision of Blacks organizing and networking at ASMS conferences, given the increase in the number of minority groups present at the conference. Christina, Michelle, and I decided to formalize her vision at ASMS in 2018. We coined the name "Black People Meet @ ASMS" with the goal of informally meeting other Black people at the conference and establishing rapport amongst each other. With ASMS going virtual for 2020, we were faced with the challenge of moving online as well. We knew it was important to still foster those relationships and provide a framework for networking, despite not being in the same place. Therefore, we decided to host our first virtual event during the ASMS virtual reboot conference – and it was fantastic. Our intention was really just to create a safe space to gauge the mental health of Black mass spectrometrists during this period of uncertainty, but we also played a few MS-themed games to help us get to know each other better.

We used our social media platforms to publicize the Black People Meet @ ASMS event and our "suggested resources" flyer, which subsequently attracted the attention of ASMS leadership. During the ASMS 2020 virtual reboot, we were asked to give a short presentation on systemic racism. There were obviously quite a few social movements at this time, so they asked us to discuss what systemic racism is and why it’s important. CBM evolved from there!

Ulmer: Our first virtual event really opened our eyes to the possibilities of CBM. Traveling is a hindrance to many people, but the virtual option allowed us to easily expand our scope. We want to connect people across the world and provide resources for as many people as possible. This goal was one of the reasons we changed our name from Black People Meet @ ASMS; we don’t want to limit our efforts to one conference. The Coalition of Black Mass Spectrometrists better reflects the wider scope of our initiative in the future.

Even at the beginning, our hope was to eventually transition to a point where we could have more influence; for example, providing suggestions for more diverse speaker line-ups, giving talks, and highlighting each other’s research.

Jones: In addition to this, we wanted to create a space to foster professional development opportunities and, more importantly, career opportunities. We want to interact with different companies looking for mass spectrometrists, and ensure Black people are aware of and being considered for these positions.

Reid: I’ll just add that it’s important not to underestimate the initial goal of CBM – to create a sense of comfort and belonging when you attend these events and might feel isolated as one of the only Black people there.

Reid: I attended Spelman College, which is a historically Black college for women in Atlanta, Georgia. For this reason, I actually feel quite lucky because I obviously didn’t experience racism there. But I recently moved to Switzerland and my experience living in Europe has been eye opening. America has its own issues with racism, but because there’s not the same history in Europe, I’ve found the racism here to be a bit more nuanced. For example, I remember having a conversation with a colleague and trying to explain to them the concept of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs). They just couldn’t wrap their head around it, and suggested (albeit jokingly) that I was racist for attending one of these colleges. I was shocked that someone could possibly interpret the situation like that. I believe this comes from a general lack of understanding about what it means to be Black in America and how deep-seated the racism actually is.

Ulmer: I had a similar experience when I was younger – I grew up in a city with two HBCUs, so I was introduced to Black scientists pretty early on. It wasn’t until I attended college that I experienced a real culture shock – because there were no other African Americans in chemistry. I immediately felt slightly isolated. On top of that, I also had to deal with actual blatant racism from certain peers or professors.

Some places are better than others, but in South Carolina, there’s still strong racial tension and people are not afraid to show it. For example, when Obama was first elected, there were many Blacks celebrating – and some unhappy white people actually started throwing trash at us from their vehicles. Unfortunately, this sort of behavior is the norm in some areas.

Besides blatant racist behavior, Blacks are forced to cope with microagression inside and outside the workplace. I remember the day Michelle asked about joining my graduate research group – in my absence – and my colleagues struggled to communicate to me that she was a woman of color. They had good intentions and knew I would probably be the best person to share what it was like being in our group, as well as resources available on campus for minority students. Eventually they just said, “Yes, Michelle is Black, so talk to her because she’s another Black woman.” It really shouldn’t have to be that hard – and that’s a shame. It was an honor to speak to Michelle about my graduate experience, and I agree with my colleagues that I was probably the best person for her to speak to at the time. Despite the ongoing racial tension, Blacks have this unwanted responsibility of still having to show up, meet deadlines, and be resilient as if nothing is wrong.

Jones: I grew up in a predominantly Black area of Louisiana, and I had an HBCU around the corner. I wouldn’t say I necessarily saw a lot of Black scientists, but from a young age I was exposed to viewing Black people as professionals and knowing that was an option. It was only once I got to a more diverse high school that I even learnt about mainstream white culture. At my predominantly white college, I experienced quite a lot of microaggression; for example, being excluded from certain study groups, my intelligence being questioned, or being asked to show someone a dance because “all Black people can dance.”

But when I got to graduate school, I really had a shock – despite being somewhat prepared by some amazing mentors during undergrad for what it meant to be a Black person at these schools. As a Black person, you have an innate understanding of how important it is to be inclusive – and we tend to be very intentional about our inclusivity; for example, if I meet someone from a very different background, I’ll try to steer the conversation to common ground. But this was not my experience in grad school. One group conversation about the TV show “Friends” sticks in my mind – everyone was so shocked that I’d never watched it. I remember thinking, “Do you not realize that I’m Black? Do you not realize that I have a completely different cultural experience to you?” The show was in no way representative of my life and thus of no interest, but they couldn’t get it. The story sounds minor, but I don’t think people truly understand how such behavior constantly adds to feelings of isolation. Luckily, my research group was great, but the department at large was clearly struggling to create a safe and comfortable environment for people of color.

Ulmer: The key thing is representation. We need to be present on boards and we need to be given the opportunity to present our research and our perspectives.

Jones: More fundamentally, we need to have a better understanding of how to interact with people who don’t necessarily look the same or share the same experiences, to engage more people in the sciences.

Reid: Overall, it’s about helping people understand that bringing people together from diverse groups actually benefits everyone and creates a space to uncover novel scientific ideas. There are so many solvable diseases that are specific to a single population and not addressed until that group or population are engaged in the research question. And that’s why initiatives like CBM are so vital – it’s about bringing people together to encourage and prompt analytical science to really explore new and diverse facets of research that can benefit the community as a whole.

Reid: Engaging with the conversations going on in this area and being openly inquisitive is a good start. As a Black person, you have to teach yourself about your history – it’s not taught to the extent it should be in history lessons in the US (or elsewhere). The onus should not be on Black people to educate you as well. It’s really up to everyone as an individual to go out there, educate themselves, and truly engage in these discussions – not just on the surface level, but the root causes.

Jones: There’s a lot you can do as an individual. When you’re in a meeting and there’s someone that’s left out – whether they’re Black or not – make sure they are involved and feel welcomed. Be an advocate for people – make sure Black people are considered for the same opportunities and speak up if someone is being overlooked. Some people will say these are small actions, but they can really make a difference. The other thing I always say is to check the people in your life – start noticing if people are being biased and call them out on it! Educate them as well, because the people you surround yourself with become your biggest circle of influence.

Jones: They can go to NOBCChE and recruit people for their organizations to help build representation. All organizations should be striving for true representation – whether in your staff, your keynote speakers, or the research posters you present. Further to this, make sure you’re creating these spaces for people to safely report any racist behavior and ensure they are able to talk about any issues when it comes to racial tension in the workplace.

Ulmer: The honest answer is that we are sculpting as we go. We’ve already expanded beyond our initial intent for CBM. We’re in the process of forming a board – to make sure it’s not just the three of us and our thoughts – and that will ultimately help us build a more comprehensive organization.

Jones: We are really excited about the future of CBM – especially after the overwhelmingly positive response from the ASMS virtual event. We learned that people wanted to meet more, so we’ll be scoping out how to implement more networking and create more events in the future.

We’re glad the current social movements have caught a lot of people’s attention; the timing has obviously propelled CBM and allowed us to build unexpected momentum this year. We hope this momentum continues. Often the efforts die down after headline-grabbing events, so we hope people continue to support positive change, continue to listen, and try to address the issue of systemic racism in analytical science.

*Part of our "Holding a Mirror to Analytical Science" cover feature