As I write this, the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) is only days away. This event, hosted by the UK, will see heads of state, campaigners, and climate experts assemble in Glasgow to decide how best to tackle climate change in the coming years. The hope is that most countries – and all G20 nations – will commit to serious action to limit global warming to the 1.5 °C levels set out in the Paris Agreement. Personally, I look forward to hearing the outcomes of these discussions – and I’m sure many of you feel the same way. Why? Because, despite the bleakness of the situation, there’s still plenty we can do to improve the state of our planet.

Have humans irreversibly damaged the environment? Yes. Could it get worse? Absolutely. Is all hope lost? No. Even last week, the US EPA announced a strategic roadmap to research, restrict, and remediate PFAS and hold polluters more accountable (1). This is a massive change for those in the analytical chemistry field working hard to keep the public safe from toxic “forever chemicals.”

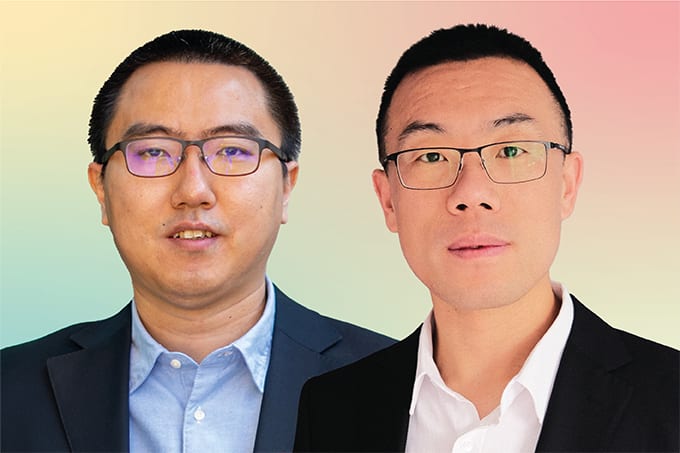

In our feature, four gurus of environmental analysis (Jacob de Boer, Derek Muir, Diana Aga, and Valeria Dulio) discuss key issues around the regulation of chemicals like PFAS and try to imagine a better future for the field. As Jacob says, “In an ideal world, we wouldn’t need regulations or permits.” Nonetheless, a great deal of progress has already been made to keep pollutants under control. “We’ve seen MS become much more sensitive, much faster, and much more reliable. And it’s our job as analytical chemists to apply that pressure for better methods,” adds Jacob.

As Lutgarde and Jeroen look to the next generation of analytical scientists, they ask, “When a young science enthusiast who wants to make the world a better place thinks about potential career paths, they might immediately turn to biomedical science – with the prospect of curing cancer. But why not analytical science – with the prospect of saving the planet?” They argue that there’s a common drive among analytical chemists to solve practical problems with real-world implications. And, from what I’ve learned speaking to many of you in this field, I agree – you are certainly not just waiting on the world to change. It seems there are many reasons to be hopeful about the (analytical) world to come.