A team at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, Germany, have discovered that film fans can change the chemical composition of the air around them – with their breath. The team screened 9,500 people for potential emotion signaling molecules during 108 screenings of 16 different films. They found that the chemicals emitted varied from scene to scene, allowing them to pinpoint exact moments in the film that elicited strong emotional responses. Originally, the team were looking to answer a different question: are the chemicals that we breathe out significant to global atmospheric chemistry? The group decided a trip to the football stadium might help. “With 30,000 people in a confined space you can get a nice average breath spectrum. Based on that we could multiply the average by 7 billion people and see whether the numbers were in any way important on a global scale,” says Jonathan Williams, from the Air Chemistry Department. From that came the idea of capturing the “chemistry of group euphoria”. Williams says, “We thought it would be cool if, when there was a goal and everybody got ecstatic at the same time, we could capture the chemical signature of a goal!”

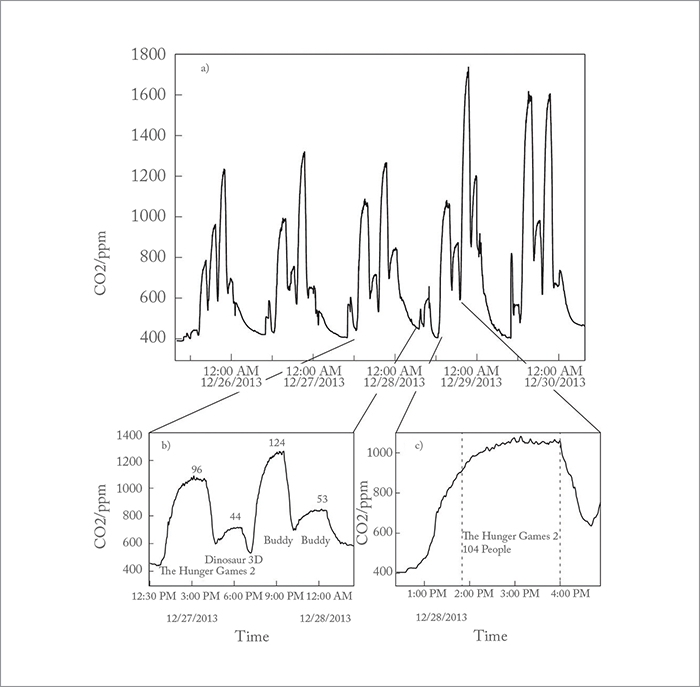

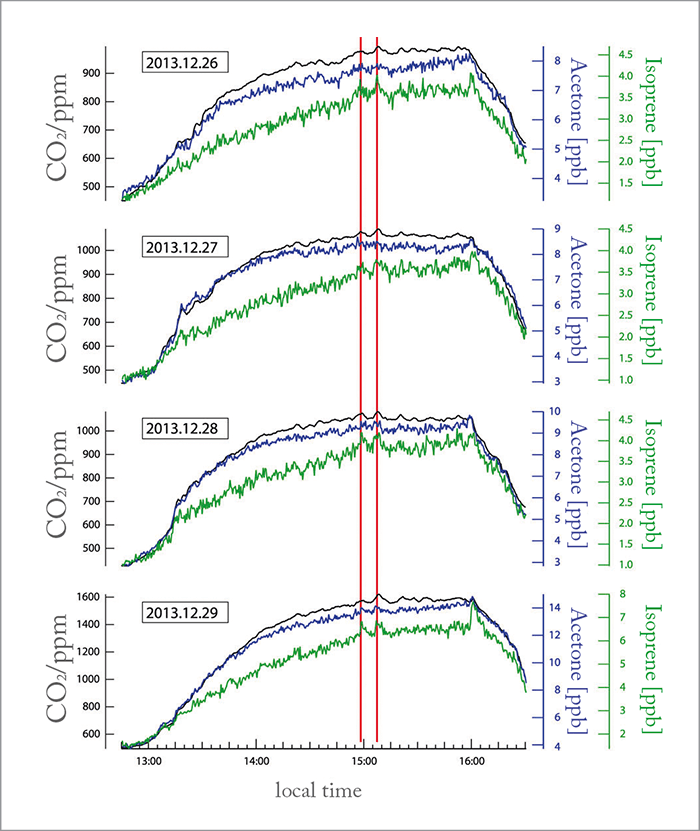

Unfortunately, the match ended 0-0. The team decided that a movie theater could be an good substitute location. “A cinema is a really elegant way of measuring the potential linkage between what we breathe out and our chemical state of emotion,” Williams says. “We essentially got people in a nicely ventilated box and then frightened them or made them laugh. All the time we flowed air over them, and simply measured the sequence of peaks. We were able to measure on-line, so could see clearly and in real time when everyone was frightened and we got a peak in CO2.” Film events labeled “suspense” or “injury” elicited the strongest chemical changes, leading the team to speculate that this “chemical communication” may function as a form of group signaling beneficial from an evolutionary perspective. They used Ionicon’s proton transfer reaction mass spectrometer (PTR-MS) to track the trace gases. “It runs on water – you essentially pass a lightning bolt through it and that forces the water to carry an extra proton, giving you H3O+ instead of H2O,” Williams says. “You simply put these reagent ions through ambient air, and they try to pass on that uncomfortable extra proton. Fortunately for us, the proton does not transfer to nitrogen, oxygen, argon – all the main components in the air – so we are able to detect a whole host of organic species with the system – acids, alcohols, aromatic compounds, and so on.”

A crucial advantage to conducting the experiment in a cinema was reproducibility. “I looked at the results for The Hunger Games 2 and noticed that when the same film was shown on a different day to a different 250 people, for some of the chemicals the peaks occurred in the same place,” says Williams. “Of course, as a scientist – and especially as an analytical scientist – you want reproducible results. In a cinema, you can do that by showing a film multiple times.” Williams describes the paper as “a signpost publication” and says he would expect a lot of atmospheric chemists to be interested in developing the findings further. “These temporal changes in chemistry are there to be seen in a group of people in a controlled environment – and you can use those signals for whatever purpose,” Williams says. He suggests it may also have uses in biology, film-making, advertising and psychology: “A lot of psychologists try to do experiments where they attach probes or have to wear a mask – which can influence behavior. To be able to non-invasively measure someone’s reactions could be very useful.”

References

- J Williams et al, “Cinema audiences reproducibly vary the chemical composition of air during films, by broadcasting scene specific emissions on breath”, Sci Rep 6, 25464 (2016). DOI: 10.1038/srep25464