With new achievements and changes every month – from personalized medicines to artificial intelligence and automation – it is becoming increasingly challenging for the biopharmaceutical industry to keep up.

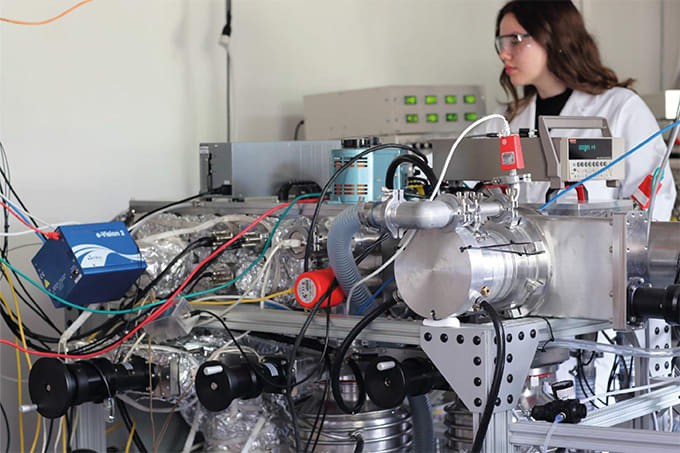

We spoke with Jennifer Römer (expert in mass spectrometric protein characterization at Rentschler Biopharma SE, Laupheim – a contract development and manufacturing organization (CDMO) for biopharmaceuticals, including advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs)) and Jens Meixner (product manager for CE and HPLC systems at Agilent Technologies) to find out more about the challenges faced by users and manufacturers alike – in a rapidly evolving world.

What are some of the emerging analytical challenges facing the biopharma industry?

Römer: The complexity of biopharmaceutical proteins poses enormous analytical challenges. For antibody analysis, many manufacturers offer solutions that can often be used universally after minor adjustments, such as the development of suitable devices and consumables, simplification of applications, and even support for analytical questions through suitable workflows, including the recommendation for various separation and detection parameters. The situation, however, is different for mAb-like or even non-mAbs, such as highly glycosylated enzymes. These pose new challenges for manufacturers and users. The heterogeneity of the molecules means the evaluated analytical methods quickly reach their limits, and due to the interference of the signals, it can be difficult to determine, for example, an intact mass or the charge heterogeneity of the protein. As a result, the demand for better separation and detection performance is rapidly growing. Here, sample preparation plays an increasingly important role in reducing the heterogeneity of the molecules prior to separation.

And how about in the world of instrument manufacturing?

Meixner: Well, increasing complexity is an ongoing challenge here, too – though it’s interesting to see how the nature of those challenges is changing. Take multidimensional HPLC, for example – a technique that was developed more than 20 years ago. The biggest challenge when Agilent launched its first 2D-LC instrument around 10 years ago was hardware related; specifically, valve technology – the heart of multidimensional chromatography. Today, the main bottleneck is the software. It has taken a long time to get to the point where software can automatically program valve steps, flushing processes, and minimal user input injections. But for laboratories facing complex analyses, the right software is needed to bring everything together – and to make the technique sufficiently user-friendly.

What are users of analytical instrumentation looking for in 2024? Presumably, user-friendliness?

Römer: During any analytical process, easy-to-use hardware and software are desirable. Further, from a user’s point of view, intuitive control of analytical devices and automation are of particular relevance. Increasing efficiency and minimizing possible sources of human error (whether by suggesting parameters and methods to achieve optimal analysis results or by drawing attention to missing eluents or samples) both bring significant benefits to the analyst and the lab. Supported troubleshooting – within the method or on the device – also makes work in the laboratory much easier.

It is advantageous to be able to define different users to adjust the level of detail according to the activity of each employee. For example, it should be possible for the primary user to successfully carry out the analysis without major hurdles but still give the expert the opportunity to develop methods and conduct troubleshooting. In other words, it is important to keep the hardware and software as simple as possible – but, crucially, while still maintaining high capability and managing complex methods. This twin need poses significant challenges – especially for the increasingly sophisticated analytical instruments and workflows, such as multidimensional separation techniques and mass spectrometers, that we need to keep up with the increasingly complex analytical questions.

Meixner: For decades, HPLC development has been focused on better specifications for the instrumentation itself. For example, increasing the maximum pressure by a further 100 bar. The focus has shifted dramatically in recent years, perhaps because the hardware is doing a great job. The focus, as I alluded to earlier, has transitioned now to software. “Usability design” – the concept of developing software with the user in mind, has only been established recently in the analytical world. However, customers have asserted the importance of simplistic software. Younger users in particular, spend many hours a day on their mobile phones, tablets, and computers, and are accustomed to intuitive controls. These users have come to expect this same level of easy usability when controlling software in the laboratory. Historically, hardware-centric companies have to develop into software companies. But because of the strong competition for software developers and talent, this process is not easy.

And as instruments and analyses become increasingly complex, we must face the fact that data evaluation will also continue to grow in complexity – a grand challenge where AI and machine learning seem destined to play a crucial role.

What challenges – or opportunities – does AI present?

Meixner: From highly complex data analysis to invoice verification, AI has already reached many areas on the part of manufacturers and users – with more to follow. Due to the learning component in AI, this will develop exponentially.

From the manufacturer's point of view, the big challenge is to integrate this new technology into products as well as into company processes. Initial tests show the success of AI. Publicly accessible AI tools (ChatGPT, Bing Chat, and so) work well – especially in the area of service copywriting. In the future, if we are using AI to draft initial support documents, such as manuals and brochures, this can be done fairly instantly, enabling us to speed up this part of any project (whether product launch or otherwise). The use of AI in the field of software programming is also an enormous leap forward. Simple software scripts can now be written completely independently by the AI.

The challenge, however, lies in the integration of AI and data security into the products themselves. Currently, many software products for controlling instruments and data are proprietary. This will have to change to be able to work with publicly available AI programs. Potential areas of AI application could be within method creation and development, including “Design of Experiments,” as well as data evaluation with pattern comparison, database comparison, and complex mathematical calculations. In these two fields, the learning component of AI could turn out to be especially helpful.

Römer: From the user’s point of view, it would be helpful to analyze, automate, and optimize recurring processes using AI and machine learning. These include, among other things, laboratory procedures, production processes, analytics, and especially data evaluation. However, as Jens said, this topic sparks another discussion surrounding data integrity, which must be guaranteed without exception – making it difficult to use publicly available systems and programs. In addition, it is important to maintain a certain degree of transparency in the functioning of the systems so that the process and results remain traceable and contained.

Are there any other complexities you’d like to discuss? What about analytical workflows?

Meixner: As a manufacturer of analytical instruments, nearly every new development begins with the question of the customer’s workflow. When developing these workflows, customers don’t start from scratch. There is usually existing software and device infrastructure that must be taken into consideration. The complexity of the customer's analytical workflow has increased greatly in recent years (mainly because of networking and automation), which poses major challenges for manufacturers and suppliers of analytical instrumentation. If you cover every possibility, the instrument or software very quickly becomes too complex, the learning curve too steep and the installation too challenging. It requires intelligent solutions with a simple starting point to give the expert the opportunity to adapt.

Römer: As a CDMO, we act as a service provider of biopharmaceutical analysis. These analytics help to monitor and optimize the manufacturing processes – and they are the basis for quality assurance of biopharmaceutical molecules and an invaluable asset for troubleshooting throughout the entire process. Thus, increasingly complex molecular formats and time sensitive deadlines demand optimal analytical workflows – and result in daily challenges.

It is important for manufacturers/CDMOs to continue to optimize established analytics and reduce their complexity; intuitive solutions that help increase automation, simplify workflows, and minimize sources of error are all welcome.

As I noted earlier, the goal is to minimize the complexity of control and maintenance, while still having the opportunity to access a suitable level of detail to guarantee optimal working conditions for the different users and questions.

Any final thoughts?

Meixner: I think I speak for both of us when I say it can be difficult to introduce new approaches into the sometimes more conservative biopharmaceutical industry, where there is such strong regulatory oversight. However, increased analytical challenges call for more intelligent, user-friendly, and automated instrumentation. These new technologies will be essential in boosting efficiencies in the lab, as well as driving analytics forward to allow us to answer more questions. Manufacturers and users of analytical instruments need to work collaboratively to continue to understand the needs of individual users, laboratories, and of the industry as a whole; only then can we develop joint solutions to successfully continue industry growth.

Image credit: Agilent