Elizabeth Treher is the founder of several entrepreneurial organizations and was an invited member of the first U.S. delegation to China for Education and Training. Trained as a radiochemist, she led multinational chemistry projects in industry, government, and academia, and the start up of a corporate university serving 22,000 global employees. A graduate of Washington University in St. Louis with an M.A. and Ph.D. in nuclear and radiochemistry, Liz also attended Northwestern University and was a NSF Postdoctoral Fellow. She has more than 85 publications and patents. Wiley & Sons published her most recent book for technical managers.

Do you leave work with a knot in the pit of your stomach, worrying about interpersonal conflict between staff members in your lab? Do you get caught between staff members and flounder, not sure whether to intervene or ignore the situation? Do you tend to see the positive side of conflict or does the mere thought of tackling a problem make you want to call in sick? Conflict can arise from many sources in organizations. You may face ‘internal conflict’ between responsibilities of your work and family, or other personal demands. As a manager, you may experience ‘interpersonal conflict’ between two of your staff, or ‘hierarchical conflict’ between you and a staff member. You may struggle to manage an individual who was formerly a peer and close friend. There may be ‘organizational conflict’ between departments or companies. As long as conflict is not resolved, organizations and those who work in them will feel the impact. Thomas Crum (1) teaches that by replacing reflexive, unconscious “I win - you lose” reactions to conflict with conscious “you and I” approaches, we can capitalize on conflict to achieve goals and objectives.

- Thinking about your own approach to managing conflict, do you typically:

- Tend to ignore the signs of conflict, hoping the issues will resolve themselves over time.

- Allow others to ‘win’ in conflict situations, so you can avoid confrontation.

- Stand strong, perhaps forcing others to back down, until you get your way.

- Try to identify the issues and work toward a solution where everyone involved gives a little.

- Take the time to work with others to solve the conflict together, even finding solutions not considered initially.

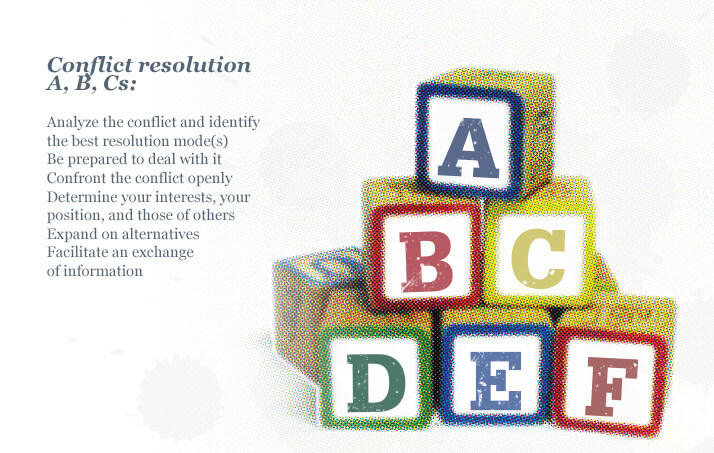

Most of us have one or two preferred ways of dealing with conflict that we rely on too heavily (see The Five Approaches to Managing Conflict). There are many questionnaires to help you assess your conflict management style, such as the Thomas Kilmann Conflict Inventory (2). The terms used in the assessments vary, but the styles are generally consistent with the five-mode conflict resolution model developed by Robert Blake and Jane Mouton (3). It shows conflict styles based on assertiveness and cooperativeness. Moving from low to high on the cooperativeness and assertiveness scales leads to an increasingly collaborative mode of conflict resolution.

In conflict situations, understandings, feelings, perceptions and assumptions all come into play. Perspectives differ and assumptions interfere. As hard as it may be when you are sure you are in the right, you will benefit if you listen and try to understand the concerns of others. Peter Drucker put it perfectly when he said, “The most important thing in communication is hearing what isn‘t said.” Ideally, conflicts should be managed face-to-face, to use as many communication “channels” as possible. Communication is enhanced when we use multiple senses. This means that leaving a voice mail message or sending an email or text message are typically not as effective as face-to-face communication, where there is opportunity for questions and feedback. To guide your approach, see ‘Quick Six to Resolving Conflict’. Remember, conflict is a state and conflict resolution is a process. Making assumptions about another’s perspectives does not lead to resolving conflict and may make it worse. Managers can easily provoke defensive communication simply by making comments based on their own assumptions. For example, when you provide feedback to an employee, which of the following comments is least likely to create conflict?

- a. You were disruptive during our meeting today.

b. You interrupted Alison and Jim several times during the meeting. - a. Your lab work was sloppy and careless, so we have to redo all the tests.

b. By omitting the second step, you didn’t follow the SOP, so we have to redo all the tests.

Effective conflict management is an important skill in managing a team (5, 6). Yet, few of us actively examine our own approaches to conflict. Accept the need, and make the effort to broaden your reactions and approaches to dealing with conflict.

Liz Treher is CEO and founder of The Learning Key in Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania, USA. Join her on March 19 at Pittcon 2013 at Short Course #141 to learn more about conflict resolution and discuss your own challenges.

Liz Treher is CEO and founder of The Learning Key in Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania, USA. Join her on March 19 at Pittcon 2013 at Short Course #141 to learn more about conflict resolution and discuss your own challenges.

1. Focus your attention.

- Look for key points and underlying goals or principles.

- Avoid evaluating or judging; keep an open mind.

- Prove you are listening with non-verbal signs.

- Listen between the lines; pay attention to voice inflection, rate of speech, and non-verbal cues.

- Take notes to capture key words and ideas, and refer to them.

2. Avoid Assumptions

- Summarize to check for understanding.

- Ask questions to clarify/amplify.

3. Separate the people from the problem. Focus on “what ” not “you.”

4. Focus on interests, not positions. Interests are the unspoken driving force behind demands and positions. Identifying interests opens the way for resolving conflict. Ask questions to challenge your assumptions; be willing to listen to understand other’s concerns and interests.

5. Explore options for mutual benefit. In thinking about positions (yours and others), look for underlying interests. Which are most important?

6. Identify an overarching principle or standard to help shift conflict to a broader perspective. Examples include, “It’s better to settle this between ourselves than go to our manager” and “Accuracy has the highest priority“.

(3-6 from the book “Getting to Yes” (7))

References

- T. Crum, The Magic of Conflict, Simon and Schuster, 1987. T. Kilmann, The Thomas Kilmann Conflict Inventory, CPP, Inc. R. Blake and J. Mouton, “The Fifth Achievement”, J. Applied Behavioral Science 6(4), (1970). C. R. Rogers and F. J. Roethlisberger, “Barriers and Gateways to Communication”, Harvard Business Review (July-Aug 1952 and Nov-Dec 1991). K. J. Behfar et al., “The Critical Role of Conflict Resolution in Teams: A Close Look at the Links Between Conflict Type, Conflict Management Strategies, and Team Outcomes”, J. Applied Psychology 93 (1), 170 –188 (2008) R. Peterson and K. J. Behfar, “The dynamic relationship between performance feedback, trust, and conflict in groups: A longitudinal study”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 92,102–112 (2003). Fisher, R. & Ury, W., Getting to Yes, Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981.