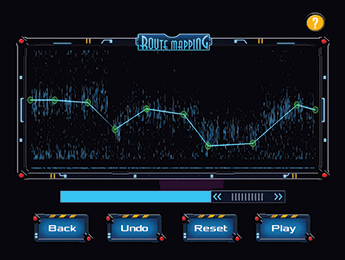

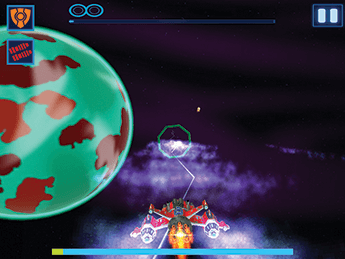

If you’ve ever dreamed of piloting your own spaceship through an asteroid belt while simultaneously performing cutting edge cancer research, then “Play to Cure: Genes in Space” is the app for you. While you’re busy plotting your course and harvesting “Element Alpha” in the intergalactic (genetic) landscape, what you are actually doing is inspecting gene copy number variation from state-of-the-art data gathered from the 2012 METABRIC (Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium) study (1).

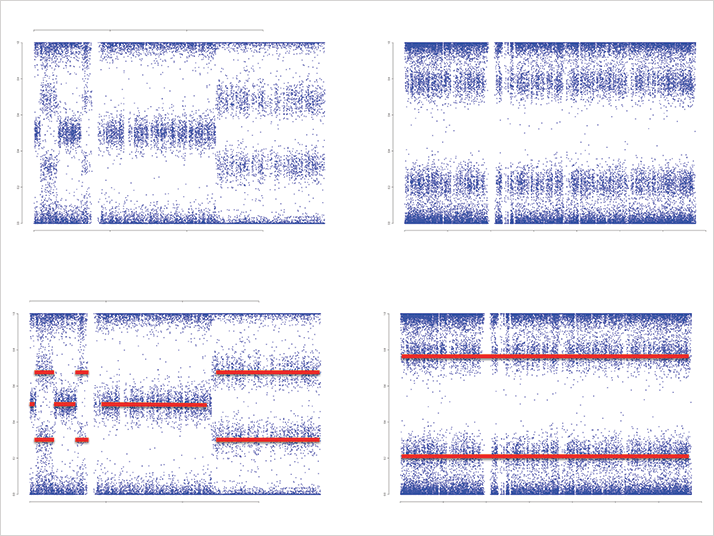

METABRIC looked at patterns in the tumors of nearly two thousand women and concluded that there were at least ten different subtypes of breast cancer, each with its own genetic fingerprint (Figure 1) But that left an ocean of genetic data to crunch.

Oscar Rueda from Carlos Caldas’ group (Breast Cancer Functional Genomics, University of Cambridge) was involved in the project. He explains that, “The cancer types have different DNA copy number profiles. In some cases these form a narrow peak that describes the driver gene in that particular subtype; in other cases it is not so clear.” Current statistical methods can detect copy-number aberrations in the genome with an accuracy of 90-95 percent, Rueda says, “But for difficult cases, the human eye usually does a better job. It can spot the patterns in the copy number profile and distinguish whether a real copy number change is happening or if it is

just noise.”

The problem is, manual curation of 46,000 plots is not feasible. “Plus, we would still have problems with the inter-rater agreement, due to subjective scoring,” says Reuda. And so, the idea of a video game was born, tapping into the inexhaustible passion for tablets and smartphone games.

“Play to Cure” is available from Apple and Google Play stores and it’s fair to say that it’s addictive – consider it as a much more useful replacement for Flappy Bird. “We expect that with a large number of people analyzing each case, the average results will be more accurate than any statistical method,” says Reuda, “but of course we will have to formally prove it.” If the project is a success, look out for more opportunities to put your game addiction to good use. “I think it will open the door to many other problems that can benefit from crowd sourcing initiatives,” Rueda says.

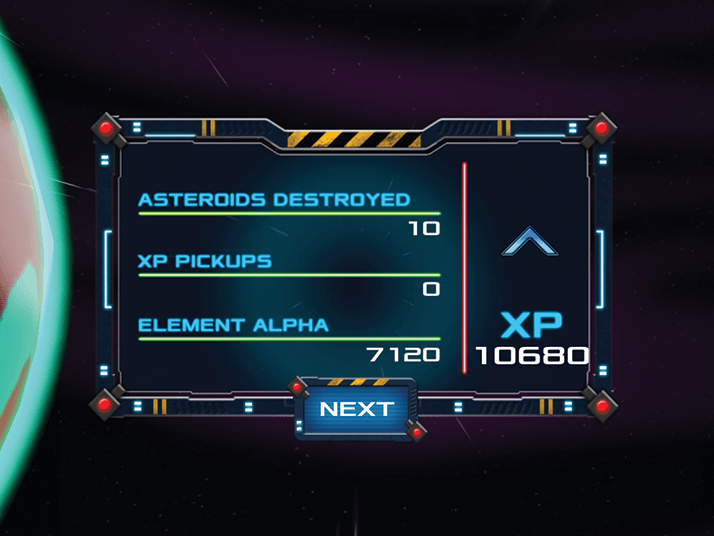

Can you beat the (meager) success of The Analytical Scientist’s first mission? Asteroids destroyed: 10, Element Alpha: 7120. Post your scores in Comments. And may the force be with you.

References

- Christina Curtis et al., “The genomic and transcriptomic architecture of 2,000 breast tumours reveals novel subgroups”, Nature 486, 346–352 (2012). DOI:10.1038/nature10983