Judgment Data

Sitting Down With...Glen Jackson, Ming Hsieh Distinguished Professor of Forensic & Investigative Science, West Virginia University, West Virginia, USA.

False

Sitting Down With...Glen Jackson, Ming Hsieh Distinguished Professor of Forensic & Investigative Science, West Virginia University, West Virginia, USA.

Receive the latest analytical science news, personalities, education, and career development – weekly to your inbox.

Glen Jackson is Professor of Forensic and Investigative Science at West Virginia University, USA.

False

False

December 10, 2024

2 min read

Analyses of fossilized feces, intestinal contents, and vomit reveal how dinosaurs adapted to climate shifts

October 4, 2024

1 min read

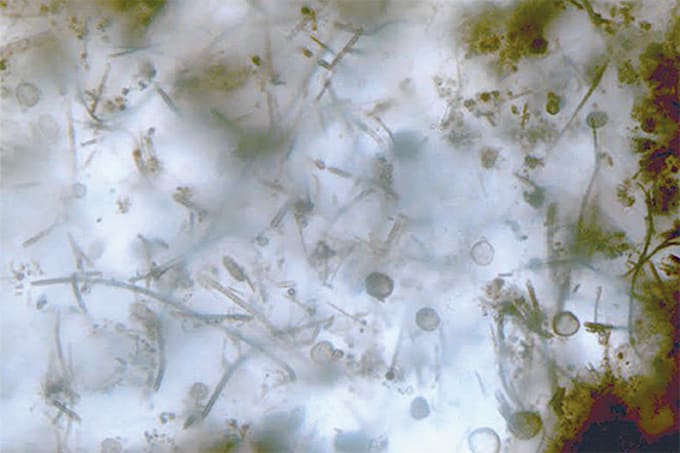

A new imaging technique using specially coated indium tin oxide (ITO) glass slides reveals key bioessential elements in ancient microfossils – suggesting that life 1...

October 11, 2024

8 min read

Why the discovery of indium tin oxide glass slides ultimately led Akizumi Ishida and Kohei Sasaki to shed new light on early life on Earth – and to jump for joy

October 17, 2024

5 min read

Ani Martirosyan walks us through her histological and synchrotron X-ray analysis that provides new insights into infant mortality in Iron Age Iberian populations

False