A recent paper in PLOS One about using laser-stimulated fluorescence (LSF) to find fossils couldn’t have been better timed given the success of the recent movie reboot, Jurassic World. The research group demonstrated that the technique can be used to more effectively find and analyze dinosaur fossils – and provide greater detail in the process (for example, soft tissue information), which is invisible using more traditional methods, such as ultraviolet light (1). “It’s been known for some time that some fossils, but not all, fluoresce under UV light,” says Thomas Kaye, a research associate at Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle. “It’s also known that ants often pick up microscopic fossils and take them to their anthill. So if you shine a UV light on an anthill at night, you can pick out the glowing specimens.”

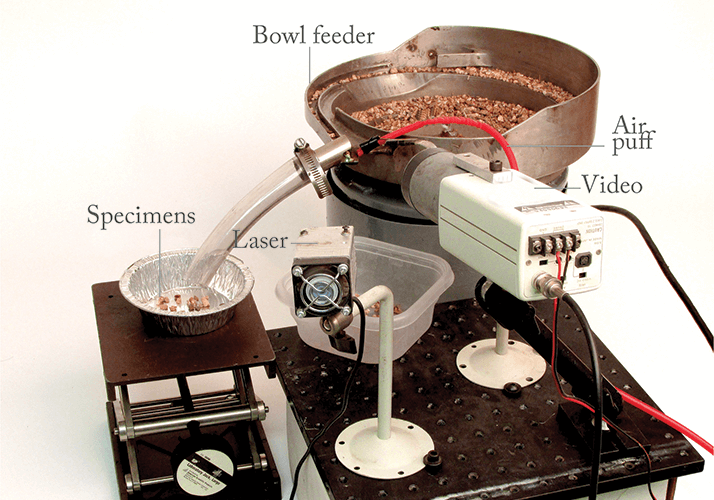

Compared with UV, LSF provides an order of magnitude improvement in the signal-to-noise ratio. After reading about the advances made through the use of LSF in biology, Kaye wondered if it would stimulate the fluorescence in dinosaur bones. And it did. “Since then, we’ve progressed the technique to develop a kind of automatic sorting machine. The system feeds gravel from the anthill through a small opening and we shine a laser on that opening. When something comes through that is brighter than normal, it gets separated,” says Kaye (Figure 1).

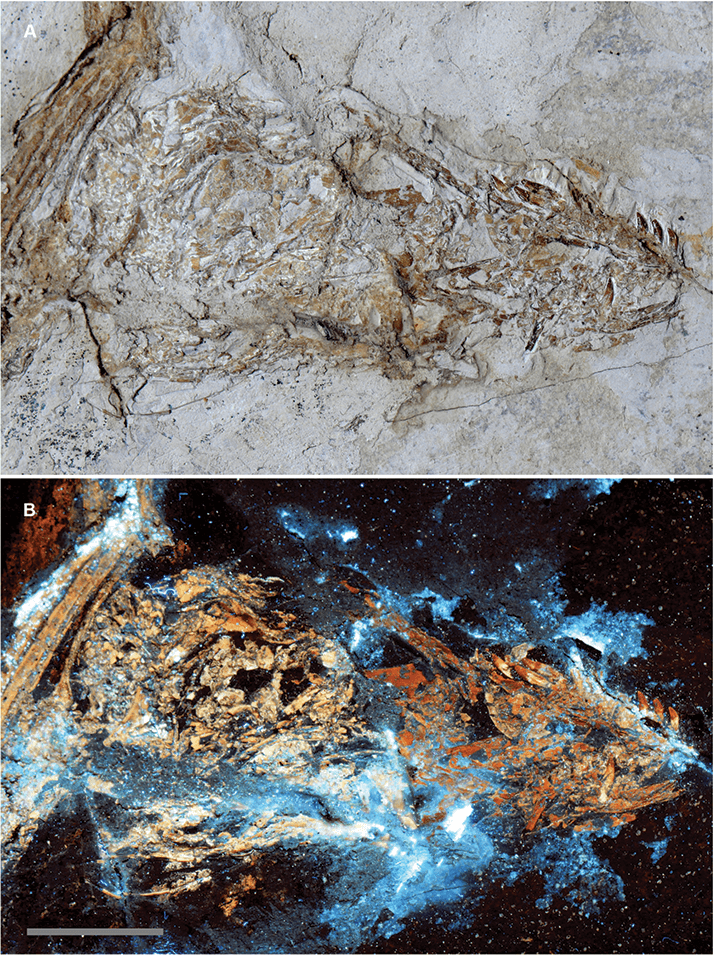

But using LSF as a fossil sorter is only the tip of the iceberg. As lasers have become cheaper, Kaye and his collaborators have started using blue lasers, which produce greater fluorescence than the green lasers the group had been using before. “We could use a blue laser to identify some previously unknown specimens because it can fluoresce fossils where the bones are buried beneath the matrix,” says Kaye (see Figure 2).

After travelling to China, one of Kaye’s students from the University of Kansas was able to fluoresce a Chinese feathered dinosaur at a museum. To her amazement, the feet, which were just bones to the visible eye, showed the foot pad and scales when fluoresced. “We were stunned! When you look at something that looks like a piece of sand and a few bones, you wouldn’t think this level of geochemical preservation was there. The fluorescence sorts out one geochemical fingerprint from another at a very minute level – so differences between the scale and the skin of the foot show up as color differences and illuminate the original soft tissue that used to be there. Some of the things we saw were like looking at an x ray of a chicken,” says Kaye. “This could alter the paleontology field since experts may have been chipping away at soft tissue information that they didn’t know was there.” Now, the researchers are working on a second paper that will showcase in more depth what can come of using LSF on dinosaur fossils. The group also hopes to create a portable system that can use hyperspectral imaging. Kaye explains, “This would allow us to put together a spectroscopy for each of the minerals that we find are fluorescing differently. In an ideal scenario, we would create a data cube; each layer in the cube would represent a particular wavelength and if you stack the cube vertically it would create a low-resolution spectrum. From the spectrum, we could determine more about the minerals and what they are doing, and how this detail came to be preserved.”

“In China, they have quarries where hundreds of people are toiling every day to split shale and search for fossils. They will split open a mountain of shale to find one feathered dinosaur fossil. One of the things we’d like to attempt is to bring a portable system into the field at night and to shine the laser on the quarry wall. Even if there is just the edge of a bone sticking out of the wall it should light up. We could scan an entire wall and see where the lights line up, which would be an indicator of where to dig.” And if you’re wondering what Kaye thinks of the Jurassic World film – he still hasn’t seen it. “I’m out in the field, so I’m miles from a cinema. But I’m sure people will be eaten, which is always good in dinosaur movies...”

References

- T. G. Kaye et al., “Laser-Stimulated Fluorescence in Paleontology,” PLOS One (May, 2015), DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125923