By analyzing artifacts and other physical remains, archeologists allow us to imagine how our forebears lived. But such mental constructs lack a key component of our sensory experience – smell.

“Olfaction has a major effect on how we perceive and navigate the world,” says Barbara Huber, doctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. “Yet studies of the past have so far been largely odorless.”

Nor real surprise there – smells of the ancient world are typically long gone by the time an archeologist arrives on the scene. But what if researchers could overcome the methodological challenges to reconstructing scent using modern analytical technologies? Well, that’s exactly what Huber and her colleagues are proposing (1).

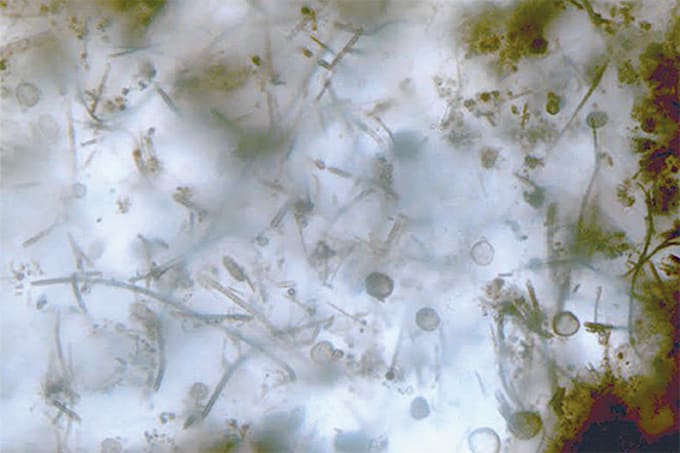

“Although the original smell might be gone, we are still able to find tiny remains of the substances that produced scents in the past,” says Huber. “These organic remains are often invisible to the naked eye, but they are still present on a molecular level. We can find them in a number of different samples, from archaeological artifacts to dental calculus.”

The researchers highlight four classes of biomolecules that are particularly valuable for studying past smells: secondary metabolites, lipids, proteins, and DNA. Using gas or liquid chromatography-(tandem) mass spectrometry, shotgun proteomics, DNA sequencing, and bioinformatics, they believe it is entirely possible to reconstruct past olfactory landscapes.

“Studying smells can unlock another dimension of the past,” says Huber. “This sensorial perspective can help us to better understand critical aspects of past lifeways: the spices people used to flavor their meals and how these have changed cuisines over time, the perfumes they wore, the hygienic conditions at certain times, and what role cosmetic and medicine played in the past, for example. We believe that by leveraging these potent new biomolecular and omics approaches, we can open up new aspects of the ancient world, our changing societies and cultures, and our evolution as a species.”

The team is already working on a number of different studies to reconstruct the smells of an ancient oasis in Arabia, as well as ancient Egyptian perfumes and ointments using some of the methods discussed in the paper.

“This paper was meant as a call for action to encourage archaeologists to look more closely at past odors,” says Huber.

References

- B Huber et al., Nat Hum Behav (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-022-01325-7