Broadly, what are the main analytical challenges in cell and gene therapy?

There are numerous analytical challenges facing the cell and gene therapy industry, which arise in three main areas: materials, assays, and product characterization.

There are often limitations with regards to the availability of materials, as a result of a small number of vendors and suppliers. In addition, due to the limited supply of raw materials required to perform analytical methods, costs are extremely high.

By their nature, the assays that can be performed are very limited. Current general assays are sensitively limited in the LOD/LOQ required specifications. Potency assays often take two to three days to perform and are complicated procedures. The complexity of the processes also leads to a workforce issue. More generally within the sector, there is a skilled labor shortage and, although companies like ourselves have launched initiatives to combat the problem, numerous parts of the advanced therapies industry are affected – analytical science included.

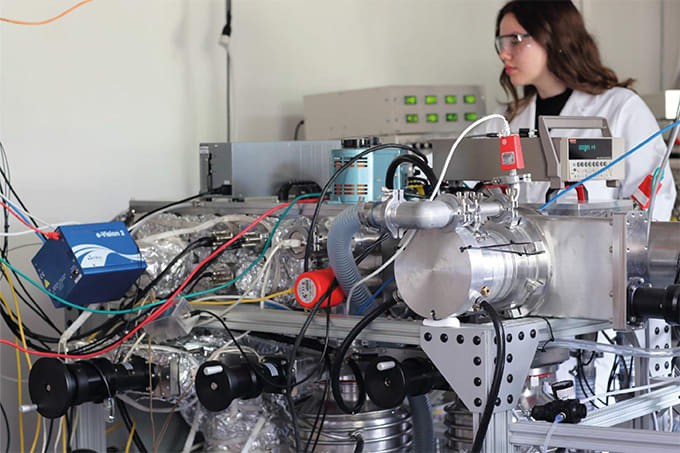

Orgenesis is a global leader in decentralized cell manufacturing; using Orgenesis’ Mobile Processing Units and Labs (OMPULs) and focusing on point-of-care services allows for “fresh product” delivery; however, such an approach brings major challenges for fast and reliable analytical method development for expedited cell product release.

As the cell and gene therapy industry matures, what role must analytical science play?

The maturation of the cell and gene therapy field has resulted in increased complexity. And as products become increasingly complex, the analytical methods needed to test them often need to be more sensitive and reliable. In-process testing in closed systems (mainly in bioreactors) is used for different real-time measurements using different types of sensors and detectors. These systems produce a large amount of vital data that might be used to assess the product state during production and predict its efficiency in the early manufacturing stages.

Traditional analytical methods are time-consuming, with low-throughput, making them unsuitable for the current fast pace of process development; it’s clear that the industry will need rapid methods for testing products’ safety, identity, and potency – and so analytical scientists will need to play a critical role in developing appropriate tools and methods.

What are the main techniques used in cell therapy analysis?

The main techniques used in cell therapy currently include cell counting – automated cell counting methods (by AO/PI, AO/DAPI, trypan blue dyes) are mainly in use – and detecting nucleic acids, or proteins. Cell biomarkers are mainly detected using flow-cytometry methods, nucleic acids are targeted by DNA/RNA, PCR, qPCR, ddPCR and DNA/cDNA sequencing, and proteins are detected using techniques such as ELISA, fluorescent labeling, and chemiluminescence. Recently, with the growing immune cell therapy market (CAR-T, TILs, MILs, and so on), new methods have been developed to assess effector cell proliferation and target cell killing assays (cytotoxicity).

What will cell and gene therapy analysis look like in 5–10 years’ time?

Being able to automate several of the time-, labor-, and cost-intensive aspects is a key target for analytical scientists, so we will see progress in this area. Indeed, automation is a key focus across the industry. In addition, further technological development will hopefully see big data and artificial intelligence (AI) tools being used for trend analysis, out of spec and stability management. In addition to these technological advancements, additional techniques will be introduced.

Sagi Nahum is Director of Product Development and Senior Scientist, and Dana Fuchs Telem is Director of Process Development, both at Orgenesi