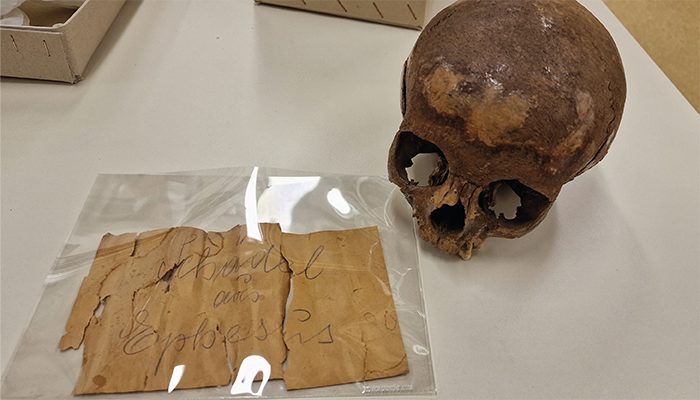

The cranium from the Ephesos Octagon in the Collection of the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, University of Vienna. The yellowed note coming with it says: “Skull from Ephesus”.

Credit: C: Gerhard Weber, University of Vienna

A skull discovered in the Octagon tomb in Ephesos, Turkey, in 1929 did not belong to Arsinoë IV, Cleopatra’s half-sister, an interdisciplinary research team has conclusively found. A combination of micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), radiocarbon dating, and genetic analysis, revealed that the remains are those of an 11- to 14-year-old boy who had significant developmental disorders.

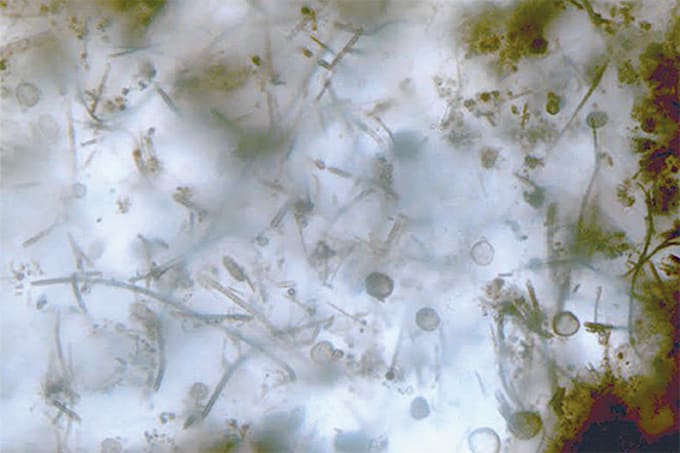

The research, led by Gerhard Weber of the University of Vienna, Austria, began with high-resolution micro-CT scans to archive the skull digitally at a resolution of 80 micrometers. Mass spectrometry was used to analyze isotopic composition from milligram-sized samples of the skull base and inner ear, which refined the radiocarbon dating process by accounting for dietary influences. This analysis placed the remains between 205–36 BCE, consistent with the period of Arsinoë IV’s death in 41 BCE but incompatible with the remains being hers.

Who Was Arsinoë IV?

Arsinoë IV was the younger half-sister Cleopatra VII – the last active ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt. Arsinoë became her rival during a power struggle for the throne. After Cleopatra was deposed in 48 BCE, Arsinoë aligned herself with Egyptian forces opposing Julius Caesar, who supported Cleopatra’s claim to the throne. Arsinoë briefly ruled as queen during this rebellion but was captured and taken to Rome after Caesar’s victory.

Following her release from captivity, Arsinoë was exiled to the Temple of Artemis in Ephesos (modern-day Turkey). In 41 BCE, at Cleopatra’s request and with Mark Antony’s approval, Arsinoë was executed on the temple steps, ending her challenge to Cleopatra’s rule.

Arsinoë’s death added to the intrigue surrounding Cleopatra’s reign, which ended dramatically in 30 BCE when she died by suicide after her defeat by Octavian (later Emperor Augustus) in the Roman Civil War. Cleopatra’s death marked the fall of the Ptolemaic dynasty and the beginning of Egypt’s integration into the Roman Empire.

“Repeated tests of the skull and femur clearly showed the presence of a Y chromosome – in other words, a male,” said Weber in a press release. DNA analysis also confirmed that the femur and skull originated from the same individual. Genetic testing indicated origins in the Italian peninsula or Sardinia, suggesting the boy was part of the Roman community in Ephesos.

The boy exhibited significant cranial abnormalities, including craniosynostosis (premature fusion of cranial sutures), an asymmetrical skull, and an underdeveloped upper jaw. Detailed dental analysis revealed severe wear on some teeth while others were unused, likely due to jaw alignment issues. These anomalies may have resulted from a genetic syndrome like Treacher Collins or nutritional deficiencies such as vitamin D deficiency.

The Roman Octagon tomb, notable for its Egyptian architectural influences, was previously thought to house someone of high social status, possibly Arsinoë IV. While the reasons for the boy’s burial in this prominent tomb remain unclear, the findings suggest he was of significance within the Roman community.

“This study not only ends the rumor about Arsinoë IV but also opens up new questions about why a boy with developmental challenges was buried in such a prominent tomb,” Weber said.