In the management of marine species, knowledge of growth rate is critical. Fast-growing species have superior rates of replacement and can withstand losses to threats, such as fishing. Slow-growing species, on the other hand, are less resilient, and conservation strategies must be adapted accordingly. Fish age is an essential factor in growth rate assessment.

In the case of whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) – the world’s biggest fish – age estimates are obtained via growth bands from inside the vertebrae. Yet, there has been debate among researchers as to the intervals at which these bands are formed – some say one year per band, and others two.

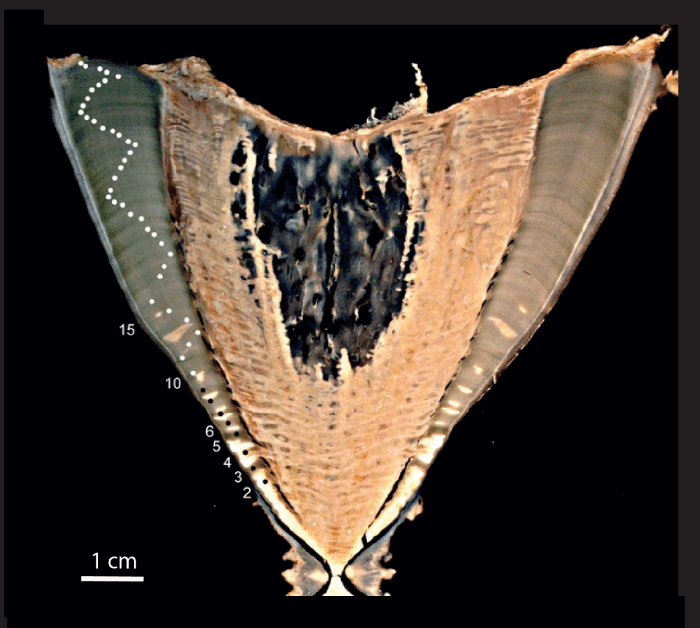

Fast-forward to Karachi, Pakistan, 2012. A beached, 10-meter whale shark, alongside vertebrae from a (now closed) fishery for the creatures in Taiwan, afforded us the opportunity to finally solve this puzzle. C14 – a naturally occurring isotope – was also released in enormous quantities by atomic bombs during the Cold War, saturating the atmosphere and making its way into living organisms. By applying accelerator MS to quantify C14 levels within the growth rings of the vertebrae of the sharks, we can arrive at more accurate estimations of age (1).

We also needed to compare our samples of unknown age with a C14 reference chronology where ages had already been designated; for this we used a C14 chronology that had been reconstructed from the earbones (otoliths) of Atlantic fish. This had a pattern of increasing C14 values identical to the surface waters off Pakistan and Taiwan, where our whale sharks had once lived.

C14 peak comparison and the known date of vertebrae collection allowed us to age the shark in Pakistan at 50 years. We then recalculated growth curves for the species, and found that these sharks are very slow-growing. Perhaps this explains why fisheries targeting this species collapse and never recover – whale sharks simply aren’t built to withstand the added pressure of human harvest.

To date, knowledge of whale shark life spans has been based largely on assumptions and evidence from other species. We thought they might reach ages as old as 100 years. Given that our 10-meter shark is thought to be 50, and whale sharks as long as 18 meters have been recorded, our study suggests that it’s not unlikely that these creatures could live 100 years.

Determining the age of these large sharks is just one part of the jigsaw puzzle that we need to complete the picture of their ecology. We still lack answers to the most basic questions about the species - how often do they breed, where do females go to pup and even where the largest adult animals are in the open ocean. Despite their size, so many aspects of the basic biology of these sharks remain a mystery, and these questions are the focus of our future research.

There is a Kenyan story that when God created whale sharks, he was so pleased with their form that he scattered silver dollars on their backs, which explains their beautiful white-spot patterning. But whale sharks are more than a charismatic part of the tropical ocean ecosystem; they are a significant contributor to the local economies of developing nations, such as the Philippines and Indonesia, where ecotourism surrounding whale sharks has lifted thousands out of poverty. And the more we know about these wonderful animals, the more hope we have of allowing future generations to also benefit from their presence.