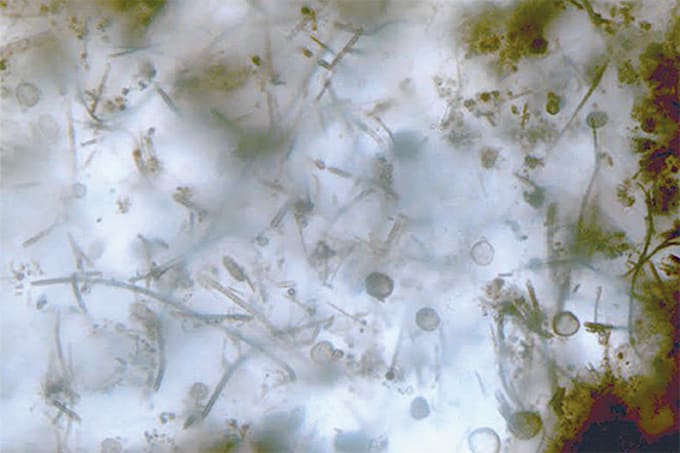

Is this individual, electronic record of results from doping tests helpful or unhelpful to sport and to athletes Herman Ram: We know from the past that athletes who dope do not simply stop doping when a new detection method is introduced; rather, the nature and magnitude of their doping is altered. The biological passport seems to be an effective tool in counteracting prohibited blood manipulations.

The passport is not just a tool to gather information on which a new doping case can be built (such decisions are not taken lightly; a lot of information is needed to build a concrete doping case). The passport does help to select athletes who deserve to be monitored more intensely. In doing so, the process is improving ‘regular’ doping controls that determine the presence of a specific substance. An example is that the number of EPO-related positives has increased since the introduction of the biological passport.

Douwe de Boer: To successfully apply the biological passport, one must be able to guarantee that factors other than doping compounds or methods do not result in a sanction. Unfortunately, nobody can give such a guarantee. Some factors are covered; the anti-doping authorities ask for relevant information during sample collection, such as the altitude of performance, gender, and information on blood loss. However, for other potentially confounding factors, the legal responsibility rests with the accused athletes. If athletes do not give an explanation for abnormalities in their biological passport, it is considered that those abnormalities are caused by so-called doping manipulation. Not every accused athlete is in a position to investigate such unknown factors, which limits defense and weakens their legal position. Another reason why athletes are not currently in a strong legal position is because they tend to assume that doping is only a problem for other athletes – they are not always proactive about standing up for their rights when the anti-doping authorities write or revise regulations. Those in a better position to do so should protect the rights of athletes, but they – the anti-doping authorities and analytical chemists – are primarily concerned with their own position, and not that of the athletes. We must be extremely careful. The anti-doping testing system should not be hell-bent on catching every guilty athlete at the expense of convicting innocent athletes too. Currently, there are question marks over what risks are reasonable.

What should the criteria be? And how should thresholds be applied?

Douwe de Boer: The list of prohibited substances and methods need greater gradation in the form of threshold values. Only if the concentration of a given compound in a biological sample is above a certain threshold value should a disciplinary process be started. Today, threshold values are in place for a very limited number of compounds, meaning that analytical detection of extremely low concentrations can start the disciplinary process. Legally, the detection of one molecule (if possible) would be sufficient. That’s crazy. As analytical developments enable lower and lower limits of detection, regulations should shift towards setting reasonable thresholds. Pollution of drinking water with waste medication and contamination of food with veterinary drugs have led to situations where unconscious intake of compounds that are prohibited leave athletes in a perilous situation. Prohibition of substances should have a sound scientific basis, which first requires a clear definition of the performance-enhancing effect. That’s assuming that we focus only on performance enhancing effect rather than ethical or health considerations. The current list of banned substances, which was developed over the last 50 years ago, set out to protect “doping victims.” In other words, the rationale for banning things at the outset was impact on health; subsequently, health, fairness and performance enhancement contributed jointly to the rationale; and now some of us may prefer a purely performance-enhancement rationale. Such a shift would present a significant challenge and it may prove difficult to find consensus worldwide.

Herman Ram: I agree on this one: a list that is based on science would be preferable – a list that puts an emphasis on performance-enhancing properties. We state so every year in our reaction to WADA’s draft List of Prohibited Substances and Methods, but the fact of the matter is that in a World Anti-Doping program the opinion from The Netherlands is just one of many. We favor in-depth discussions on the performance enhancing properties of, for example, opiates, alcohol and cannabis. Regarding thresholds, the current rules allow for one lab to report lower concentrations of a banned metabolite than another lab. From a “catch as many dopers as you can” point of view this makes sense: you do not want to let a cheater get away with remnants of exogenous banned substances when you have verified the presence of them in a scientifically correct way. But we should be careful not to report too low concentrations, as the clenbuterol-in-meat experiences have shown. And we have had experiences like this before, for example, when it was found that the anabolic steroid boldenone can be produced endogenously as well. You are bound to run into problems when you lower the detection limit on a continuous basis, but these sorts of new findings will also advance science.

Are all accredited labs up to the job? If not, how can they be improved? Herman Ram: Doping analysis is a special topic. It engages forensics, medicine and law in a very specific environment: the world of athletics. But doping laboratories also share a lot with other types of analytical labs: all analytical experts can learn from each other, with open dialogue being the key to improvement. We need the following: agreed-upon guidelines, equivalent to the International Standard for Testing and its Technical Documents; double-blind EQAS samples to secure proficiency; and an innate scientific interest to understand the results. I believe that these criteria are largely being met, but this does not mean that improvements are not possible.

All WADA-accredited labs are strong – the mere fact that labs sometimes lose their accreditation proves that there is a strict monitoring system in place. Revoking the accreditation of the lab in Rio de Janeiro almost on the eve of the football World Cup and ahead of the Olympic Games shows that the system is working. One improvement would be inter-laboratory exchanges of samples; this would strengthen the program from both scientific and PR points of view. But the current approach has a long history: the B-analysis is always performed in the same lab as the A-analysis, which means that many practical issues would need to be resolved.

Douwe de Boer: Analytical laboratories have an important role and there is no reason to suspect that they are not doing their utmost to fulfill their mission. However, some analytical laboratories are limited, based on budgets and/or local expertise. The anti-doping authorities should invest in those laboratories. Analytical laboratories can apply for investigation grants but, in practice, the high-level labs are in a better position to receive funding – WADA’s system punishes even relatively low-level operating laboratories. Adequate support to increase the overall level of analytical laboratories might help create a uniform, standardized level of testing. Right now, that is not the case. Analytical chemists must contribute actively to discussions on doping policy; they are part of the anti-doping problem/solution. At the same time, the tendency for politicians to have an increasing amount of influence on doping policy should be addressed.

What are the implications of the Jadco resignations in November 2013? Douwe de Boer: Some athletes are not being tested adequately; those of Jamaica might be a good example of that. If the ongoing investigations prove the media claims to be correct, the Jamaican Anti-Doping Commission (Jadco) did not have an adequate testing program. Eleven of its commissioners resigned as the news broke. Such testing disparity is not fair, period. As stated, adequate support of relatively low-level national anti-doping authorities might be an effective way to deal with such unfairness.

Herman Ram: First of all, Jamaican athletes are not under any extra suspicion in comparison with other well-performing athletes. It will be a fatal blow to sports when every extraordinary performance becomes synonymous with doping suspicions – that is exactly why the anti-doping system needs to be at the highest possible level. We cope with all sorts of doping continuously. If ‘old-style’ doping gets the reputation of being ‘old and forgotten’, it will automatically turn into ‘interesting and thus new’ doping. That’s one of the specific aspects of this field. Our goal is to supervise possible doping habits of all elite athletes, so the overall suspicion of doping use in elite sports will be at the lowest level possible.

How far should the pursuit of doping athletes be taken? Are there any limits? Douwe de Boer: Without a doubt, there are parallels between our approach to the wider drug problem and sports doping. In both cases, the more we try to achieve the goal, the more difficulties appear. The difficulties may stem from a lack of financial resources (more effort requires more money), the right to privacy (increased unannounced testing at any time of day undermines the privacy of athletes), or inequalities in testing in different places (see previous answers). Wider society should decide how much effort is appropriate and what priority the doping issue should receive. Anti-doping authorities and analytical chemists obviously consider their tasks and roles to be high-priority, but this may not be in line with the majority opinion.

Herman Ram: The phrase ‘War on Doping’ has been used before, but not by us. This is not a war; it is a continuous effort to defend sports, and those who compete, and perhaps to retain a certain sense of morality, even though morality may change over time (and so, therefore, may the doping regulations.) Certainly, the harder you push, the more resistance you feel. But, if there is clear evidence that an athlete is using doping deliberately, we will push. Do not forget that analysis is just one side of our work. We also try to educate athletes and their support personnel to think about the effects of their decisions. Elite athletic achievements are possible without doping and, in the end, both individual athletes and sports in general are better off in an environment where they are not forced to take potentially harmful substances. That is why we will keep on doing our work.