The mammalian nose is a marvellous “smell” (chemical) detector that technology has typically been unable to rival, particularly when it comes to differentiating very similar smells or chiral molecules. Now, researchers from the University of Manchester in the UK and the University of Bari in Italy believe that odorant binding proteins may hold the key to more sensitive – and selective – biosensors (1).

Many have tried to develop artificial sniffers with varying degrees of success, but according to Krishna Persaud, professor of chemoreception at Manchester and one of the study authors, these are usually based on traditional gas sensors. “They may be metal oxides, conducting polymers that change in electrical conductance when exposed to a vapor, or other devices such as surface acoustic wave devices or quartz crystal microbalances that measure mass changes when molecules adsorb onto a surface,” says Persaud, who has taken a different approach. “We have used a naturally occurring odorant binding proteins to produce a biorecognition element that mimics what may happen in nature.” Odorant binding proteins are found in the mucus of the mammalian nose and also in the antennae of insects where they function as carriers of small molecules to and from the olfactory receptors. They are extremely stable and capable of binding a variety of different molecules.

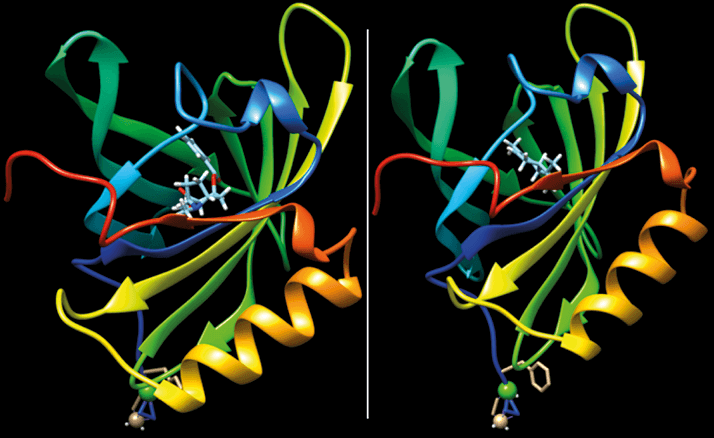

The team designed the methods for producing odorant binding proteins using molecular genetic expression systems, and also found a way to immobilize the proteins onto electrodes while retaining normal activity. “We also worked out how stereoisomers would fit into the binding site (see Figure 1),” says Persaud. At the University of Bari, the proteins were incorporated into the gates of field-effect transistors, creating a sensor that could produce a small current when an odorant molecule binds to the proteins. The project is part of the Marie Curie Early Researcher Training project (FLEXSMELL) funded by the European Community and coordinated by Luisa Torsi, another author of the work, at Bari. According to Persaud, the current work shows proof of principle – the next task will be to create a a more easily manufactured device, which could find applications in food quality and environmental monitoring, and in the medical and forensic fields.

References

- M. Y. Mulla et al., “Capacitance-modulated Transistor Detects Odorant Binding Protein Chiral Interactions”, Nature Communications (2015). DOI:10.1038/ncomms7010