For over a century, the spectacularly preserved skin, spikes, and hooves of so-called “dinosaur mummies” from Wyoming’s Lance Formation have puzzled scientists. Long assumed to be fossilized flesh, these duck-billed Edmontosaurus annectens specimens are now revealed to be something else entirely: microbial clay templates that formed during decomposition.

Published in Science, the new study led by Paul Sereno (University of Chicago) uncovers the preservation secrets of two newly discovered Edmontosaurus specimens – a late juvenile and an adult – found near the original 1900s site in eastern Wyoming. The juvenile is the first subadult dinosaur mummy and the first large-bodied dinosaur with a fully preserved soft-tissue silhouette, including neck and trunk crests. The adult specimen preserves the full row of tail spikes and shows evidence of true hooves – the earliest yet identified in any tetrapod.

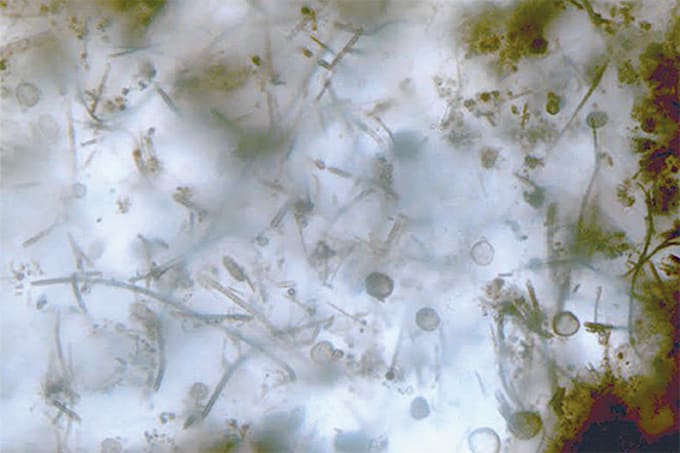

However, detailed imaging and elemental analyses overturned the idea that these features are fossilized tissue. Using optical microscopy, CT scanning, electron microscopy, and X-ray spectroscopy, Sereno’s team found no trace of organic material. Instead, the soft-tissue features were replicated as delicate clay layers – less than one millimeter thick – sandwiched between sandstone beds.

The researchers propose that these clay layers formed as microbial biofilms colonized the surface of the carcass during decay, stabilizing its outer shape before burial. The result is a 3D “template” preserving intricate external features – including a midline crest and tail spikes – previously thought only possible in oxygen-deprived environments like lagoons or seafloors.

The findings suggest that this mechanism expands the range of environments in which soft-tissue morphology can be preserved. Rather than a quirk of exceptional fossilization, such clay templating may help explain soft-tissue finds in more energetic, oxygen-rich fluvial settings.

The study also revises our vision of Edmontosaurus. The midline crest and tail spikes hint at a more complex and possibly display-oriented skin structure than previously appreciated – closer in some respects to modern squamates (lizards and snakes) than to early reconstructions.