Early embryonic exposure to a common environmental pollutant can disrupt development and skeletal formation in fish across multiple generations, even when later generations are raised in clean conditions, a new report shows.

The research shows that brief early-life exposure to benzo[a]pyrene – a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon produced by fossil fuel combustion and industrial activity – alters growth, survival, and skeletal development in medaka fish, with effects persisting in unexposed offspring.

Using medaka as a model, the researchers exposed embryos to environmentally relevant concentrations of benzo[a]pyrene during the first eight days of development, before raising all fish in clean water. Despite the absence of further exposure, reduced survival, delayed hatching, and skeletal abnormalities – including craniofacial deformities and spinal curvature – were observed across multiple generations. While some physical traits showed partial recovery in later generations, skeletal defects remained elevated.

To investigate the biological basis of these long-lasting effects, the team applied untargeted metabolomics to embryos from the directly exposed (F0) generation and their unexposed descendants (F2). Metabolites were extracted and analyzed using ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to high-resolution mass spectrometry, enabling broad profiling of small-molecule changes linked to development and energy metabolism.

The analysis revealed widespread disruption of pathways involved in energy production, oxidative balance, cell signaling, and developmental programming. In particular, the authors identified metabolic signatures consistent with an “energy crisis” during early development, suggesting that embryos redirected limited resources toward essential organs at the expense of skeletal formation.

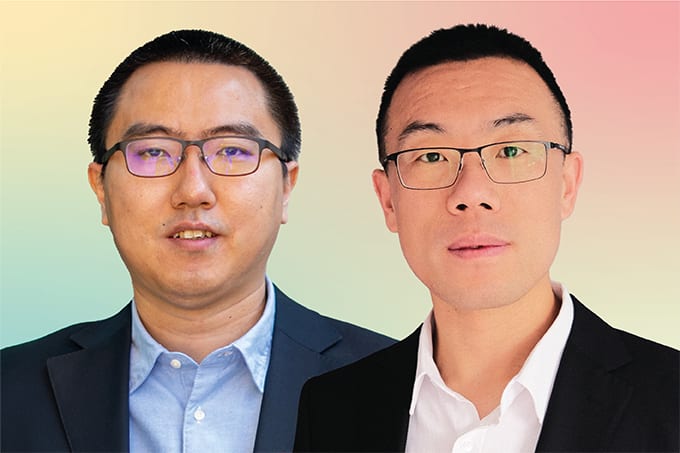

“Our results show that a short window of exposure early in life can have consequences that echo across generations,” said Jiezhang Mo, corresponding author of the study. “Even when later generations grow up in clean environments, they still carry hidden biological costs from their ancestors’ exposure.”

In later generations, some metabolic pathways appeared to compensate for early disruption, coinciding with partial recovery of body size and survival. However, the authors caution that this apparent recovery may reflect a trade-off rather than a full return to normal development.

“In the second generation, some physical traits appeared to recover, but our metabolic data tell a different story,” Mo said. “This apparent recovery may reflect a survival trade-off, where energy is diverted away from bone formation to keep essential systems functioning.”

The researchers suggest future studies could use similar approaches to better characterize multigenerational responses to environmental pollutants.