Gadgeteer at Heart

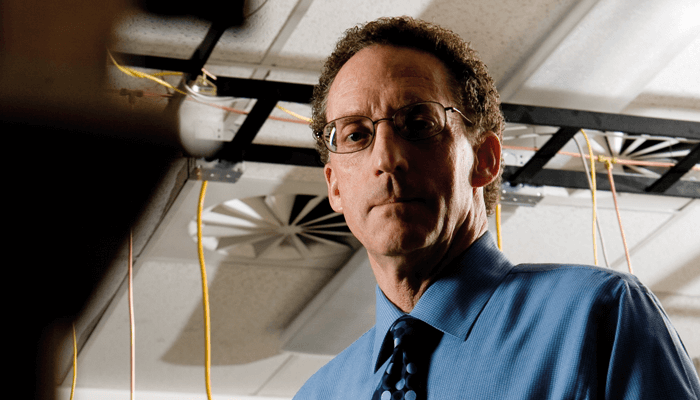

Sitting Down With... Milton Lee, H. Tracy Hall Professor of Chemistry, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA.

False

Sitting Down With... Milton Lee, H. Tracy Hall Professor of Chemistry, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA.

Receive the latest analytical science news, personalities, education, and career development – weekly to your inbox.

H. Tracy Hall Professor of Chemistry, Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA.

False

False

December 5, 2024

7 min read

In the second part of our interview, Michael Gonsior explores the pressing challenges in carbon cycle research, transformative tools and technologies, as well as analytical glimmers of hope

December 4, 2024

1 min read

Researchers develop more stable catalysts for dry reforming of methane – a promising method for carbon capture and utilization (CCU)

December 13, 2024

1 min read

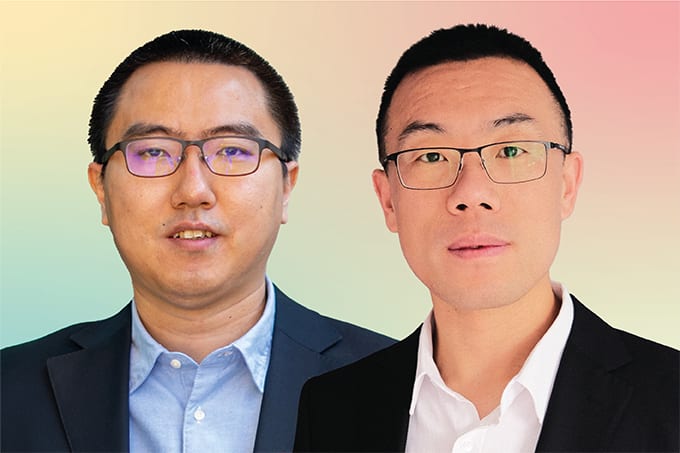

Using nanopore technology, Chang Liu and Xiaojun Wei discuss their accessible and inexpensive new option for detecting “forever chemicals” PFAS

False