Photo credit: Jessica A. Johnson

Recent developments in device and material engineering provide foundations for emerging classes of sensors, including wearable and implantable devices for diagnosis and personalized health monitoring. To learn more about the developments of this technology and what it means for the future of diagnostics, we spoke with Amay Bandodkar, Assistant Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at NC State University.

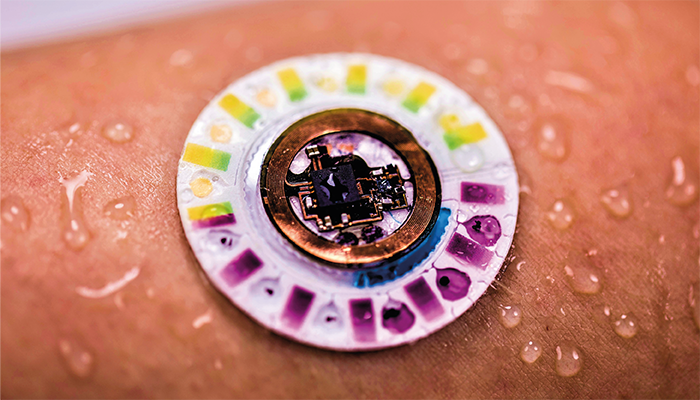

Battery-free sweat sensors (Photo credit: Philipp Gutruf)

What inspired your work in wearable sensors?

As an engineer, I’m fascinated by the complexity of the human body. Additionally, the societal benefits and unique technical challenges of wearable sensors pushed my inspiration in this area of work. Despite major developments in biomedical sensors for human physiology, much remains to be done. I believe wearable sensors can continuously and non-invasively monitor wellbeing, opening avenues for personalized medicine and benefiting those without access to advanced healthcare facilities.

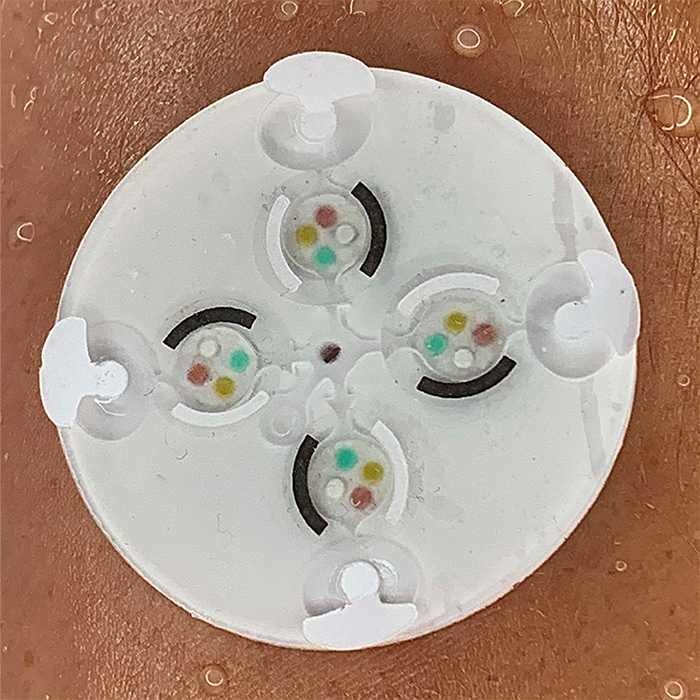

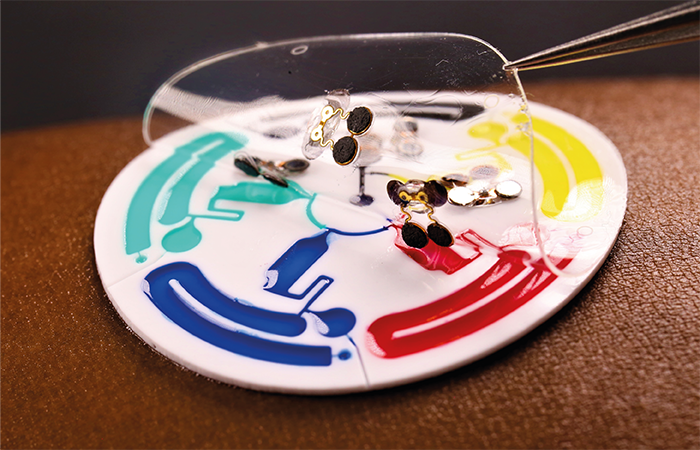

Various wearable sensors are built on the foundations of conventional analytical tools originally developed for lab-based sample testing. In our research, we’ve developed a wide range of wearable sensors that leverage analytical techniques such as electrochemistry, spectroscopy, and colorimetry.

Let's talk about sweat sampling; can you share the challenges you faced in combining electronics and microfluidics?

We faced several challenges in combining these functionalities in our wearable sensors. Firstly, we needed to prevent sweat from entering the electronic components. Secondly, we had to design thin and flexible wireless circuits that could attach to the soft microfluidics, and develop compatible sensing principles for on-skin microfluidic sweat sampling. Finally, we needed to ensure the electronic modules were small and comfortable for long-term wear.

To address these challenges, we assembled a multidisciplinary team with expertise across electrical, mechanical, and materials engineering – as well as analytical chemistry.

Finger-actuated microfluidics. (Photo credit: Nate T. Garland)

How does your battery-free, skin-interfaced microfluidic/electronic system differ from other health monitoring devices?

Typical health monitors that detect chemical markers use complex and bulky battery-powered electronics, making them difficult to use. To significantly reduce the size and weight of our wearable sensor without compromising on performance, we leveraged the concept of biofuel cells to spontaneously generate signals proportional to the target concentration.

You’re also working on wearable electro-therapy…

Electro-therapy, which involves applying small electrical fields to promote cell migration and support nerve stimulation, is often used for therapeutic applications ranging from pain relief to wound healing. We’re currently using this technique to develop low-cost, ultra-thin dressings for rapid wound healing. We’re hoping this research can produce dressings that work in austere environments with healing rates comparable to FDA-approved treatments – but at a fraction of the cost.

And what about the wound monitoring system?

Our wound monitor was built from the battery-free sweat sensing technology we’d previously developed, with some modifications. This included adding a UV protective coating for sterilization, and making the sensor independent of oxygen level fluctuations. We also developed a biocompatible coating to minimize protein adsorption and avoid harm to the wound, and redesigned the wireless circuit for wound assessment. We’re now exploring the possibilities of using this sensor for monitoring pressure ulcers and burn wounds.

Wearable microfluidics for chronometric analysis. (Photo credit: Amay J. Bandodkar)

You’ve recently switched focus to create an implantable device for monitoring neurological activity…

The neuroscience community lacks essential analytical tools for understanding brain function. As our group’s goal is to develop new sensors for improving knowledge of the human body, we’re hoping to apply our previous understanding to create neurochemical sensors that could be useful to neuroscientists.

Neurological sensors have the potential to unravel the impact of different neurodegenerative diseases on communicative pathways and support development of new therapeutics. We’re actively working with neuroscientists to develop and use our platforms in different brain-related studies.

What are your hopes for the future of diagnostics?

The future of diagnostics is very bright. I hope that, in the near future, we’ll be able to develop inexpensive, highly reliable diagnostic tools that are easily accessible for everyone – including those in lower socio-economic settings.

Looking even further ahead, I’d hope to see a seamless integration of wearable sensors that are able to monitor a whole host of biomarkers – including those that are undetectable today – for a truly accurate and comprehensive assessment of the human body. I hope the “wear and forget” technologies of the future are just as common as the modern smart watch.