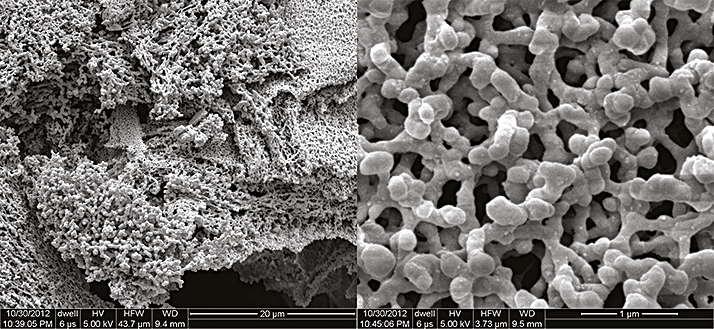

Just one percent of hydrogen sulfide in oil results in “sour crude,” which is toxic and corrosive to both pipelines and transportation vessels. Prior knowledge of its concentration is therefore of great value in oil fields. To that end, researchers at Rice University, Texas, USA, have designed nanoreporter molecules based on carbon black (see Figure 1) that can detect levels of hydrogen sulfide “downhole” (1). We caught up with consortium leader James Tour to find out more.

What inspired the design of the nanoreporters? We used our knowledge of what had already been done in biology and what the needs of downhole environments are, and coupled the two together using nanotechnology. The design of these nanoparticles for passage though oilfield rock was developed swiftly because we had a year of experience in building carbon nanoparticles for passage though the human body – we already knew how to inhibit adhesion to surfaces. Nanotechnology – the building of entities in the 1-100 nm size region – is something we’ve have been doing for about 25 years. In short, it’s really all about the convergence of expertise within our labs.

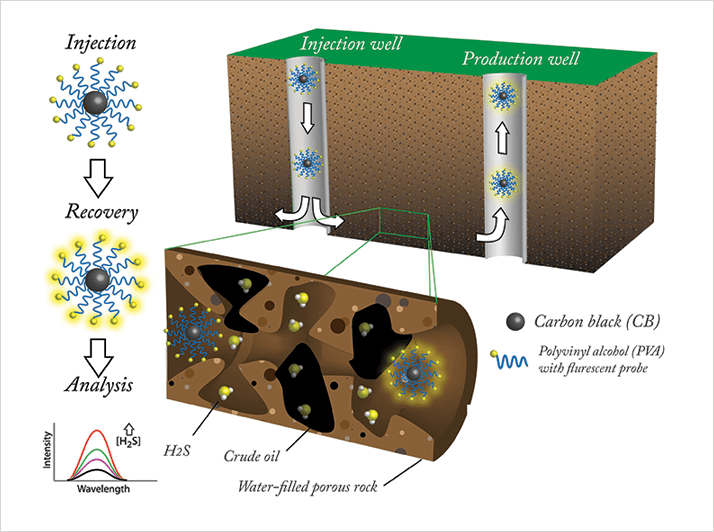

How do the nanoreporters work? When the nanoreporter particles are exposed to hydrogen sulfide (H2S), the H2S reacts with the addend on the nanoparticles and causes them to fluoresce – the higher the H2S concentration, the greater the fluorescence. When the nanoparticles emerge from the ground with the flow, fluorescence intensity can be measured using a handheld spectrophotometer (see Figure 2).

What prompted the research? The concept fits well with local interests in Houston in oil and gas, as well as my own area of nanotechnology. It was actually part of a proposed study to the Advanced Energy Consortium; we have two other papers in the area wherein we detect and quantitatively assess downhole oil using a complementary sensor.

What are the main challenges in applying the technology in the field? Getting the industry to try something new. And having a chemical company make the materials – it’s not hard but it is a new process...

What next? We will continue to develop methods to (i) better assess downhole oil quality and quantity, (ii) improve geolocation of the oil downhole – that is to say understanding where is it precisely, and (iii) facilitate removal of stranded oil.

References

- Chih-Chau Hwang et al., “Carbon-Based Nanoreporters Designed for Subsurface Hydrogen Sulfide Detection”, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces Article ASAP. DOI: 10.1021/am5009584