Yellowcake – or uranium ore concentrate (UOC) – predominantly comprises triuranium octoxide (U3O8) but different conditions during mine processing can affect the final composition. In the past, a primary method for evaluating different types of UOC was a simple – and clearly, limited – visual inspection of color. Now, researchers at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in California, USA, have applied near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) to analyze the chemical composition (1), which can help track a sample back to its origin.

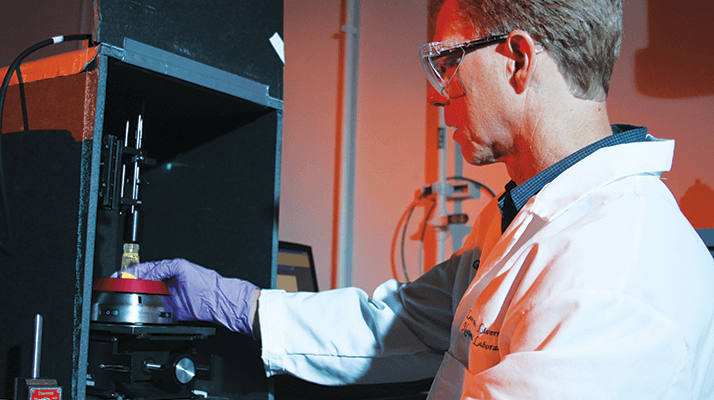

The benefits of NIRS were found somewhat by chance, says Greg Klunder (pictured), a chemist at LLNL’s Forensic Science Center and lead author of the paper. He was originally investigating the lab’s spectrometer (Labspec Pro, Analytical Spectral Devices Inc.) for use in an objective method to evaluate the color of UOC samples. “Since our spectrometer also covered the near-infrared range, we had that data as well,” he says, “The presence of absorption bands in the NIR was both fortuitous and unexpected, as this region classically measures CH, OH, and NH overtones and combination bands.” Further investigation by the team demonstrated that UOC samples from different processes have different spectral signatures in the NIR range. So, why has NIRS not been used in this application before, given its non-contact, non-destructive nature? “Nuclear forensic analysis is a relatively new area and a variety of analytical methods are being pursued to provide information about the samples,” explains Klunder. For example, mass spectrometry has been used extensively to provide trace elemental and isotopic information, but requires sample preparation that can significantly compromise the uranium samples. “Since NIR absorption bands are broader and less information-rich, there has not been as much interest in this region,” he says. “However, the ability to make non-contact measurements without consuming or contaminating the sample is clearly very useful.”

NIRS is not a trace analysis technique and can only detect components in the low percentage range; clearly, it is not intended as a replacement for mass spectrometry. Rather, Klunder believes, the method is a valuable addition to the identification toolbox in a rapidly growing area: material composition analyses in the field. Raman spectroscopy, another non-contact field technique, has difficulties with dark materials or those that have fluorescent components. The team at LLNL hopes to develop the technique further by improving the sample library and identification protocols. In the future, says Klunder, “NIR imaging could also provide spatially resolved chemical information for more heterogeneous samples”.

References

- G. L. Klunder et al., “Application of Visible/Near-Infrared Reflectance Spectroscopy to Uranium Ore Concentrates for Nuclear Forensic Analysis and Attribution”, Applied Spectroscopy, 67 (9), 1049-1056 (2013).