You didn’t have the easiest route into science… Right. I grew up in the USA in an era when women didn’t really do science. I wasn’t aware that it was even an option for me – I just knew that those were the classes I was most interested in. After high school, I followed a crooked path, attending four different undergraduate institutions (we were a roaming military family). Back then in the States, you could take classes without declaring a major, so I was taking graduate courses in quantum chemistry just because they sounded interesting – much to the surprise of my professors. As an undergrad, I supported myself with one, two or even three jobs per semester. It was hard to keep my grade point average up, but it worked out. I also had no idea that you could get paid to go to graduate school, so I worked in an environmental lab for a couple of years before starting.

Why did you become Director of the ISSC? I had reached the point in my career where I was ready to take a leadership role. I had been approached three times about becoming the head of the chemistry department at the University of Cincinnati, but I wanted to take on a broader challenge; there are people here at the cluster working with monolithic media, microfluidics and in several other fields that I’d never had the opportunity to get involved with or support. To become a great leader you have to be a great advocate, so the role at ISSC really is my dream job. For me, it’s all about separations; I don’t care what the platform is, so our multidisciplinary cluster is a great fit.

What have been your major highlights en route to Ireland? At the University of Hawaii, our group was the first to use sulfated cyclodextrin as a chiral additive in capillary electrophoresis (CE). We were also the first to use heparin as a chiral additive – and that’s taken off in some really unexpected directions, particularly in light of the adulteration in 2008. More recently, we’ve revisited some of the earlier work we did on linear solvation energy relationships (LSER) and shown that we can distinguish between different cations and anions. Despite being exciting work, it was difficult to get funded…

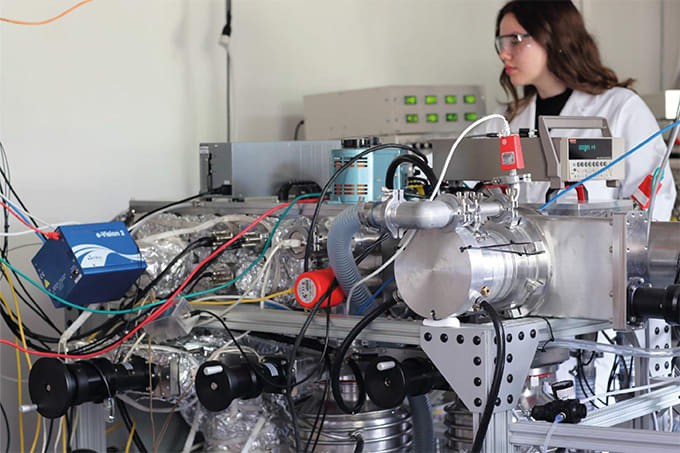

Tell us about the ISSC. The cluster was setup by Brett Paul in 2009 with funding from the Science Foundation Ireland, essentially because of the realization that separation science is a key enabling technology not only for the (bio)pharmaceutical industry, but also other sectors, such as food and the environment. There are two core programs at ISSC: materials technology and advanced platforms. Materials science includes monoliths and the work of Jeremy Glennon (University College Cork), whose group created core-shell particles that formed the basis for materials now marketed by Supelco. There is also a strong biopharma component; Brendan O’Connor is working with glycoselective ligands that are more robust and reproducible than Protein A. On the platforms side, Dermot Brabazon has been working on microfluidics and its application (along with Brendan’s work) in sample clean up. Innovative instrumentation and detection systems are another focus. What we have to remember is that it doesn’t matter how sexy our materials or platforms are if they can’t be scaled up and applied. Therefore, in most cases, we actively seek industry partners.

Commercialization is important then, but does that leave room for a more creative approach? Actually, I have mixed emotions about focusing everything on commercial success. A key part of research is serendipity. For instance, Dara Fitzpatrick, one of our ISSC investigators at UCC, is a separation scientist, but is launching a company based on broadband acoustic resonance dissolution spectroscopy (BARDS). Having a total focus on one area is not always the right approach – flexibility is also important. It’s funny, but the ionic liquid work that we’re still doing came about because one of my graduate students misunderstood me and pulled the wrong chemical off the shelf! On the other hand, researchers do need to be very aware of the interesting problems facing industry – and the need to engage with those problems to attract funding.

You will be co-chairing the 2016 International Symposium on Chromatography (ISC) in Cork, Ireland, with Jeremy Glennon – what did you take home from ISC2014 in Salzburg? I saw a couple of things that really piqued by curiosity – but I’m keeping those to myself at the moment… More generally, one thing that struck me was the vibrancy of the European separation science community. I recently gave a talk in the US about my academic career and noted that I could often partition my academic colleagues into two camps: those who think separations are magic (or witchcraft!), and those who think it’s trivial. I don’t think the average scientist in the US understands just how exciting and pioneering separation science can be. That’s why I’m really delighted to be a part of the community in Europe. Salzburg is certainly a tough act to follow. But Ireland is a wonderful place to visit. With the support of the ISC organizing committee, resources available from Science Foundation Ireland and a strong program, I feel confident that it will be a great success.