At Riva 2014 (the 38th ISCC and 11th GCxGC Symposium), Pat Sandra stood on the stage periodically shaking an imaginary separation funnel – much to the amusement of the audience. “I find it just incredible to see what people are doing in application notes,” Sandra remarked. “They have the very best instrumentation, for example to determine the composition of drinking water at the sub-parts per trillion level with triple quadrupole mass specs and gas chromatography. But do you know what their sample preparation is? They take one liter of water, add 100 ml of dichloromethane, shake it for half and hour. Then they put the dichloromethane in a vial, evaporate it down to 0.5 ml – don’t worry, it’s just going into the air – and then they inject. We need to do something about that…”

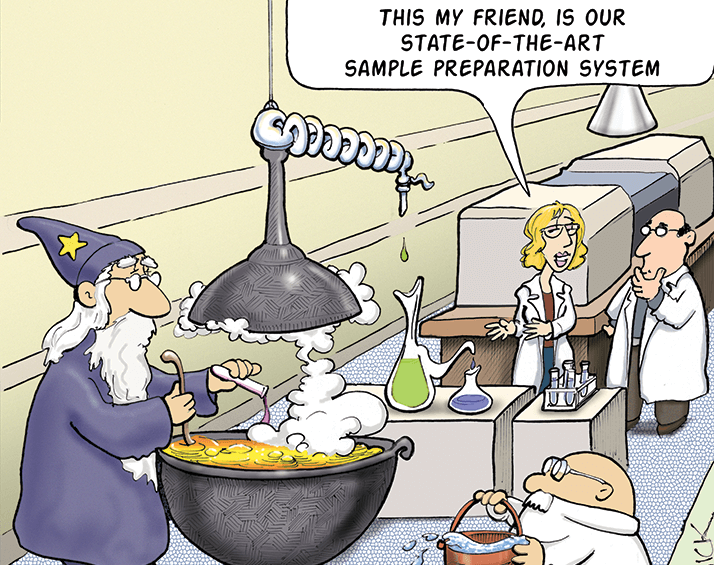

While the delivery was humorous, it had a serious underlying message: the analytical community needs to rethink sample preparation. Using Sandra’s provocative lecture as a springboard, we invited three experts to share their views and discuss the current state of the art.

Hans-Gerd Janssen is the science leader for compositional analysis at Unilever Research and Development in Vlaardingen, The Netherlands. Janssen’s team develops and applies methods for compositional analysis of food samples as well as home and personal care products. To do so, they apply a range of techniques from simple wet-chemical methods to complex instrumental approaches.

David Benanou started working for Veolia nearly 25 years ago, predominantly in research and innovation dedicated to analytical chemistry. Benanou is a specialist in separation techniques and mass spectrometry, as well as sample preparation, where he focuses on micropollutants and organic matter characterization in environmental matrices.

Frank David works at the Research Institute of Chromatography (RIC), the private research lab founded by Pat Sandra,where he is responsible for research and development projects in chemical analysis, including (petro)chemicals, polymers, food, environmental, consumer products and pharmaceuticals.

David Benanou: Analytical chemistry is a multistep endeavor: measurement is the final link at the end of a chain of operations that begins with sample prep. Sampling and sample preparation are therefore essential processes that underlie all subsequent work and impart relevance to what would otherwise be a meaningless exercise. In all of the diverse forms of analysis, sample preparation is essential. This is especially true of our activities, whatever the environmental matrices considered and even if our goal is miniaturization or the use of green techniques without solvents. Hans-Gerd Janssen: In food analysis, sample preparation is crucial. All foods contain high levels of lipids and proteins, and these two compound groups interfere in analyses. Moreover, food products are extremely complex and the spectrum of analytical questions is very diverse: for example, today, we might have to analyze the hydrogen content of an acid product packaged using aluminum foil; tomorrow, the target compounds might be protein aggregates. Frank David: To give you a sense of its importance, our company offers analytical services in many different application areas – from petrochemicals to pharmaceuticals – and in many of the challenges we face, the development or optimization of the sample prep is an essential part of the solution.

HGJ: Well, I can say what certainly has not changed: its importance. Modern chromatography and MS instruments are slightly more selective, and so able to analyze slightly more complex samples, but they have also become more vulnerable to ‘dirt,’ by which I mean compounds that are not of interest and contaminate the system. I would say that sample preparation is now more universal – think about QuEChERS or normal phase liquid chromatography as sample prep methods. There are also now better options for automation. FD: For me, there have been three major trends: miniaturization, automation, and higher throughput. Miniaturization can also help make sample prep “greener” through solvent reduction or even elimination. It is important to recognize that sample prep is part of the whole analytical workflow. The (r)evolution in mass spectrometry and the availability of more sensitive detection (for example, triple quadrupole MS in MRM mode) has allowed us to optimize and reduce complex sample prep procedures. This resulted in smaller sample sizes, and/or elimination of selective fractionation or clean-up, while maintaining or even improving sensitivity. Moreover, in several application fields, such as environmental and food analysis, customers are seeking “generic” or universal methods that allow coverage of a wider range of compounds, as Hans-Gerd also mentioned. This trend encourages the development of sample prep methods that should be less selective. DB: I offer two answers. One is that in many cases sample prep unfortunately remains the same old, time-consuming, expensive and boring technique that it has always been. The other, from an innovation point of view, is that we’ve moved from liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) and solid phase extraction (SPE) to solid phase micro extraction (SPME), micro LLE with large volume injection (LVI), PDMS-based enrichment, and so on. Following the increase in sensitivity of analytical systems, sample preparation has the same importance but can be miniaturized or adapted to be greener. Such approaches are typically well accepted by ‘clever’ analysts. From a standardization point of view, the techniques do not seem to have changed at all. Take any European country or any standard (AFNOR, CEN, DIN), and you’ll see that instead of pushing for innovation, such consortiums are happy to remain where they were 20 years ago, imposing ridiculous – and non-exhaustive – techniques on routine labs.

FD: As our activities include the development of methods for different industries, sample prep is of the utmost importance in our lab and receives appropriate attention. Our efforts focus on the three trends mentioned earlier but one should always keep the final goal of the analytical method in mind. Whether that is quantification of major solutes, impurity detection, or trace analysis, different goals require different solutions with different sample preparation approaches. DB: Sample prep is not just important for my company, it is essential! In my field – micropollutant characterization and quantification at the sub-nanogram level – good sample prep is the only way to obtain the best and most precise results possible. For the past 14 years, I have used (and promoted) a green and sensitive enrichment technique called stir bar sorptive extraction (SBSE) also known as ‘Twister.’ We have decreased our solvent consumption by around 800 percent using Twister. HGJ: Without sample preparation, trace analysis is not possible because fats and proteins immediately contaminate your system. Moreover, many compounds are present in a food product. For a detailed understanding of the quality and safety of the food, analysis of all these compounds is relevant.

HGJ: Sample prep is not really sexy. It does not use expensive, shiny instruments, and there is no theory to it. And, in fairness, it is not always important, if you have just a few samples to analyze. Modern LC, GC and MS instruments can cope with a bit of dirt… I suppose that academic research into sample prep methods is not very rewarding and does not receive the attention it deserves as there is no perceived need. However, ‘real’ users know its importance – and have problems with it! DB: Sample prep simply must remain on everyone’s radar. I would suggest that if sample prep is underestimated, then it is the manufacturers that could be blamed or thanked, depending on your point of view. Vendors push the limit of sensitivity in order to avoid sample prep and allow direct injection of the sample or extract. Indeed, that is often the way new systems are promoted. FD: Pat’s statement was indeed made ironically. Lots of attention is paid to high-end mass spectrometry and comprehensive techniques, and it could be concluded that sample preparation is simply not important anymore. However, we are convinced that “high-end GC-MS systems” (that is to say, multi-dimensional GC coupled to high resolution QToF MS) should be paired with high-end sample prep systems. It is clear that errors made in sampling, sample preparation or sample introduction (injection) cannot be corrected by using even the most advanced MS systems.

DB: It may be a controversial view but I believe that minimizing the need for sample preparation is seen as a positive by manufacturers as it enables them to sell the latest innovations in other areas with “no sample prep needed”! Unfortunately, the vendors are often more interested in selling systems than promoting real analytical chemistry.

FD: There are several issues. The fundamental one is the growing gaps between the academic world, the instrument manufacturers, and the end-users. Academic research is predominantly driven by the need for research results to be publishable, instrument companies are focused on best-in-class equipment, and industry is seeking productivity, which I define as robust solutions that give the correct answer to an analytical question in an appropriate time. These three drivers are not always in sync and are sometimes totally at odds. It is possible to attend a single session at an international symposium that begins with an academic presentation describing a new concept in comprehensive GC, continues with a company presentation of a new mass spectrometer with femtomole sensitivity, and concludes with an industry presentation that describes real issues with a simple GC-FID analysis…

Often, problems in the field relate to sample preparation, or incompatibility between some aspect of the sample – such as the matrix, solutes or concentration of solutes in the matrix – and the applied injection, separation or detection method. This can simply be down to a lack of user expertise: an example would be an effort in pesticide analysis to look for all pesticides in all foods using a single extraction method. The extracts will contain lots of matrix compounds and this will inevitably impact on productivity because even the most expensive instrument can be contaminated and need cleaning offline. Is this of concern to the instrument vendor who is mainly interested in demonstrating the perfect performance of a brand new instrument using a standard solution or to the academic researcher looking for publications and not long-term testing of method performance? No!

This issue is not new. It was raised more than 10 years ago by Konrad Grob (Kantonales Laboratory, Zurich) during one of his provocative lectures.

HGJ: I agree somewhat with Frank – I would wager that only those who must analyze large series of samples know how relevant and difficult sample preparation is. Academic technique developers who analyze five samples to demonstrate their new method are unlikely to see the need. And, as I indicated earlier, obtaining funding for research into sample preparation is probably very difficult.

HGJ: I don’t think this remark is true – at least not in the food and pharma industry. Industry assesses cost of analysis and divides that into instrument costs and operator time. It is therefore easy to calculate the need for investment and the expected cost reductions of such an investment. In the end, it is all about the return on investment. If that number is okay, there is probably money. DB: I partially agree; often lab managers believe that by spending a huge amount of money he or she will be the owner of a magic box that will avoid sample prep altogether. However, I can say that at Veolia we all push for sample preparation, whether in research or routine labs. FD: Pat’s statement is in-line with the observation that sample prep has not received much attention in the last 20 years. And the growing distance between academia, instrument suppliers and the end-user doesn’t help. However, in the end, an appropriate analytical solution should solve the analytical problem at hand, and should include automation where possible.

FD: Over the past few decades, several sample preparation methods have been developed, some of which can be automated. David has already given the examples of SPME and SBSE, to which I would add dynamic headspace (DHS). In fact, great solutions are available from several vendors. I think uptake by routine labs is often hindered by a combination of internal conservatism (both from management and in the lab), external conservatism in the form of accreditation bodies sticking to their comfort zone, a lack of expertise in the lab, and some ‘lay-back-and-relax’ mentality. HGJ: Method development in sample preparation is difficult. And during the development, the performance of a certain parameter set is difficult to quantify. Moreover, even after proper method development and validation, sample preparation methods are unfortunately not often rugged. Nominally identical samples behave differently due to variable water levels, particle sizes, and so on. Finally, I repeat: sample preparation is not sexy. There are fewer shiny expensive instruments, just cheap plastic tubes and messy laboratory benches… DB: Old-fashioned techniques, such as LLE, are standard. As Hans-Gerd indicates, a new technique needs to be validated and it takes time and money to prove that it gives the same or better results than the ‘traditional’ method. I also believe that a strong and widespread effort to lobby for and promote clean, easy and green techniques is lacking.

HGJ: Absolutely. There is no longer any need to shake large sample sizes with huge volumes of solvent. Sample size and solvent volumes can be minimized. Large volume injection is a good tool here as well. And, of course, instruments have become more sensitive so that less evaporative preconcentration steps are needed. However, there is a limit to downscaling – after all, at some point it will no longer be possible to obtain a representative sample. DB: I totally agree and am currently applying and spreading this philosophy throughout Veolia labs all over the world. Just consider the situation where we are trying to quantify a few nanograms of toxic compounds in water with hundreds of milliliters of toxic solvent. It is total nonsense! Many systems can benefit from LVI or high-speed chromatography – do customers not know that? By applying these two techniques we can make the dramatic switch from old-fashioned LE to micro LLE. FD: Modern sample preparation should indeed include miniaturization, but with respect to the minimum sample size – as Hans-Gerd noted – to ensure representative sampling. In fact, miniaturization is one of the key drivers towards “greener” technologies.

DB: I think progress can be made through lobbying and the presence of sample prep ambassadors in the various standardization consortiums. But it will take time and money. Many teams are developing new concepts for sample prep, but it will take a decade or more before they are accepted as convention. The importance of sample prep should and must become more prominent in universities. That way, the next generation of research scientists and lab managers will have better instincts for green sample prep. HGJ: In industry and quality control laboratories, sample preparation will get the attention it deserves. Quite simply, it is needed – there can be no analysis without sample preparation. Will it get the attention it deserves in academia? Perhaps in the applied analytical groups – again because they need it! However, I don’t think we will see revolutionary new methods, just evolution of existing technologies. Will it get lots of attention in academic groups that focus on technique development? I doubt it. Despite more research being needed, this is not an area where research grants are easily obtained. There are no expensive instruments, no theories, just hard work. I guess the short answer is that we need to raise awareness that, in real life, sample preparation definitely is an issue. Academia often presents new methods that work once or a few times, but are useless for routine use. FD: There is no universal solution nor a small set of “tools” that can handle all sample types for all problems. In my opinion, the bottleneck is not the availability of methods and equipment, but rather education. The lack of education and expertise is not only at laboratory level, but also at management level. There is a need for training and the availability of correct, unbiased information. International meetings should play an important role; unfortunately, most have “fully-packed” programs with parallel sessions and without ample time for discussion or critical evaluation of presented results… To conclude somewhat ironically, like Pat Sandra, I find it a little strange, indeed unacceptable, that papers are still being published that show amazing data concerning sensitivity but rely on sample preparation methods based on liquid-liquid extraction of a 1L water sample with 100 mL dichloromethane, followed by evaporative concentration to 100 µL and injection of 1 µL. Maybe Denis Desty’s 50-year-old “hammer injection method” should be applied here…