Vince Remcho: When I started my first year of university, I had a real passion for chromatography, having done some HPLC during the previous summer. Unfortunately, my passion wasn’t matched by my commitment to my studies! Instead of categorizing me as one the “party kids” and allowing me to spin off into oblivion, Harold partnered me with some grad students who would become my mentors (thank you, Henrik, Bill, and Lee). He personally kept close track of me and held me accountable. He provided me with incentives and motivation to work hard – even asking if I would like to present my work at an international conference. He did this for many others, too. He was the model mentor for a diverse array of people from all over the globe.

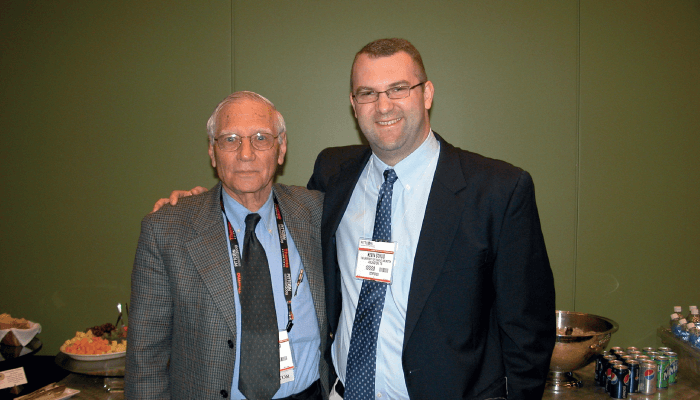

Kevin Schug: I certainly count myself among those people – I probably wouldn’t be a professor if it hadn’t been for Harold McNair. After my sophomore year of college, I sought research experience in the summer. My father was a faculty member in the chemistry department at Virginia Tech, so I asked him the names of some people to contact. I wrote to three or four different professors (all working in very different fields of chemistry) and Harold was the first to respond and make me an offer. I spent the summer with Harold and his group, learning chromatography for the first time.

I went back to school for my junior year; but 1997 was tough for me – I lost my mother in a car crash. My motivation that summer was low, but Harold arranged for me to intern as a Quality Control Analyst at S.C. Johnson Wax in Racine, Wisconsin. It was an enjoyable summer, but the job was fairly routine – analyzing products as they came off the line. The experience made me realize that I wanted more. So I ended up embarking on my PhD training with Harold at Virginia Tech. He later admitted that he sent me to that internship with the hopes of convincing me to pursue graduate school – indeed it did! Thanks, Doc, for pushing me in the right direction.

Lee Polite: As soon as you expressed interest in a specific topic, Harold would move heaven and earth to help you make it happen. I told Harold that I was interested in doing research in Ion Chromatography – the fastest growing topic back then. He immediately said, we have to get you a job at Dionex, and that he had a friend there – someone he had given his first job to (something you’d hear a lot!). Then he told me his name, his area code, followed by a number – all from memory; please note that this was someone he hadn’t contacted in years! You’d better believe that I would be very receptive, if I got a call like that.

Chris Palmer: Harold saw potential in me too, and recruited me to work as a postdoctoral associate in his lab – even though I had struggled to publish significant work as a graduate student. Once I joined his lab, he encouraged me to pursue my own research ideas and, as with Vince and others, he introduced me to an international community of scientists. Through those connections I was able to continue my research career in The Netherlands and then Japan.

Pat Sandra: In the beginning of my career, when entering the academic world wasn’t easy, Harold invited me to be part of the teaching team of the ACS course “Gas Chromatography” at Pittcon conferences. The McNair-Cramers-Sandra team was active for nearly two decades. Through the creation of this successful teaching team, Cramers offered me a visiting professorship in Eindhoven – an important step in my academic career that wouldn’t have been possible, if not for Harold!

Remcho: Harold had a gift for making people feel valued, important, and capable. He genuinely loved others and was remarkably selfless. One example sticks in my mind: in the early 1990s, there was a great deal of unrest in the middle east, and Harold went out of his way to help a visiting professor from Egypt. Harold and his wife Marijke found the scientist and his family a home in Blacksburg, connected them with the local community, and got the scientist set up to be productive in the lab. What an example to set for our research group.

Schug: I recall many times when I was walking through campus with Harold and he’d take a moment to step aside and offer help or directions to someone who seemed lost. He would always introduce himself, ask the person their name and where they were from. Often, after hearing where they were from, he would switch to their language and continue the conversation. I would watch their expression shift from surprise to a warm smile. I believe Harold got more joy out of making a person smile than anything else in life.

Polite: Kevin is right. You could tell that Harold took genuine interest in his fellow human beings. I remember one occasion Harold was speaking with an undergraduate chemistry student, his secretary interrupted and said the president of the university was on the phone for him. Harold calmly stated that he would get back to him as soon as he finished with his student. It didn’t matter who you were, he respected everyone equally.

Polite: Harold was a great communicator and a gifted speaker. But I believe the underlying driving characteristic was that, as Vince alluded to earlier, he genuinely cared about each and every individual. He was a good friend to the janitor and the CEO – and he genuinely cared about both.

Palmer: It’s true, Harold was a master communicator. He could effortlessly gauge and understand large audiences and tailor his presentation on the fly. But he was also a great listener, with a real knack for carefully considering what others had to say, and then responding with wisdom and grace.

Paola Dugo and Luigi Mondello: Communicating with Harold was easy – in many languages. He loved to share news – both good and bad – with students. And he also loved sharing pictures. Wherever he was, Harold would jump at any chance to meet friends and former students. Many students from Messina spent part of their PhD course doing research in his group (Ivana, Sara and Laura). And he was our guest in Messina many times – always with his wife, Marijke.

Remcho: I will especially miss the occasional surprise notes Harold would send my way: a post-it note on an article cut out from a journal, with a few thoughts or memories jotted on it – sent in a hand-addressed envelope. Or an email with a joke in all caps followed by, “How is your family?” Or that one time I received a heavy crate at our loading dock... Inside was an old Spellman power supply that I had modified while in grad school; “They were going to throw it away”, his note said, “and I thought it would be better for you to have it again.”

Remcho: Harold was a gentle teacher. He was open with his expectations, and they were never unreasonable. He always made it clear that his primary goal was to help me build towards the career I sought – and to help me gain the knowledge required to be successful as a scientist. For people who needed a firm hand, Harold was perhaps not the best fit – but for those who were motivated, willing to try (and try again), focused and attentive, he was unequaled. And I think that’s why the ACS short courses worked so well. Academic credentials meant much less to Harold than a persons’ level of interest and capacity to work hard.

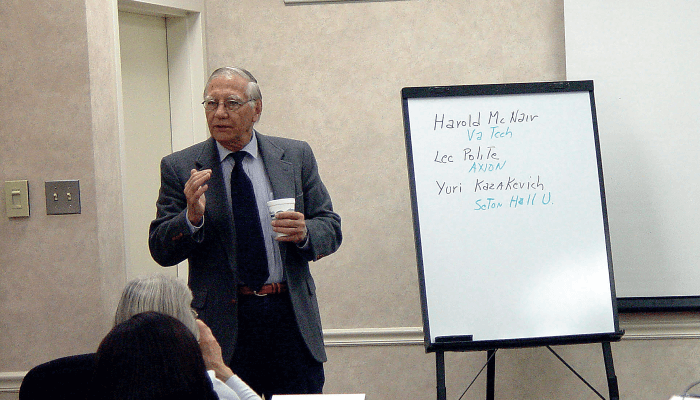

Polite: Ah, the short-courses! Four times a year like clockwork, 25–30 professional analysts from around the world would gather in Blacksburg, VA, for a week to learn chromatography from us. There was no higher priority than teaching the customer. If it meant letting a beginner practice maintenance procedures on your one-of-a-kind instrument, then so be it! This really honed our ability to explain complex topics to a wide range of customers: MD/PhDs to high-school dropouts – but each one equally important, and equally interested in learning what they needed to do their job better.

Schug: I learned a lot about teaching from Harold. There wasn’t anything “flashy.” He would communicate the essential aspects of a technique, often using his hands to effectively mimic the actions needed to perform the technique. His slides contained essential prompts, but were otherwise kept quite simple. He did not get bogged down in details, unless you asked him to go there with your questions. Even then, he was careful not to muddy the waters for others with his answers. He would often include examples and stories from his life’s experiences, which were invariably enthralling. I think that was his real gift. I miss those stories – even the ones I heard multiple times!

Palmer: Harold had an amazing skill for gaining and keeping the attention of students at all levels. He made his students feel comfortable asking questions, describing or presenting ideas, and even expressing scientific disagreements. He did this in part through clear communication and instruction, and in part through telling interesting experiential stories – threading scientific information into often-humorous narratives. I miss those too.

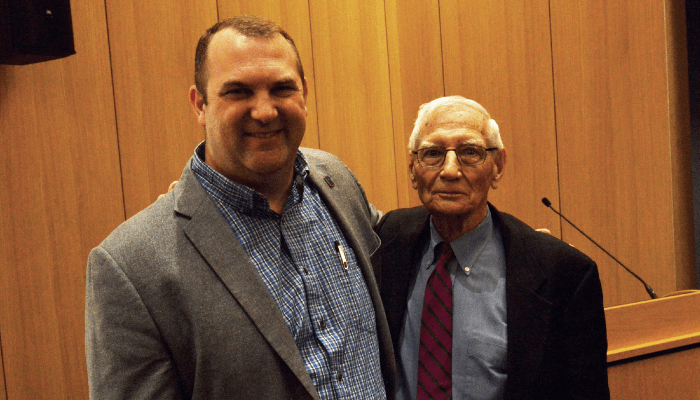

At a meeting or symposium with his graduate students, he would often gather everyone at the end of the day to ask what interesting things that they had seen or learned about, and then to discuss what the students shared. When I invited Harold to speak to my graduate class in separation science, he held their close attention for 50 minutes, introducing the historical development of gas chromatography from practical, theoretical, and personal perspectives. Several years later, those students continue to recount the stories he shared.

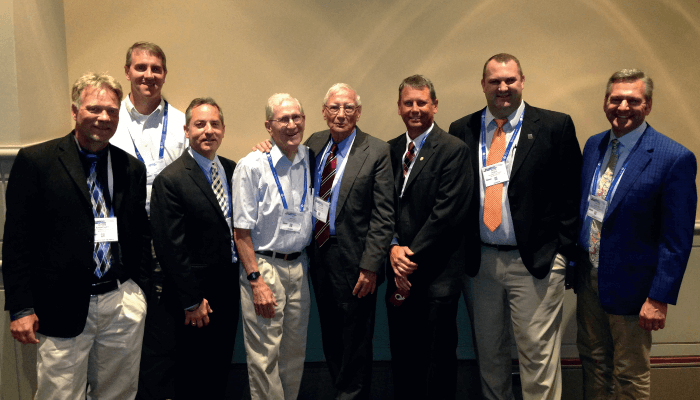

Schug: While I was pursuing my PhD at Virginia Tech, there was no shortage of visiting scientists and students from all over the world. Through his years, Harold had amassed quite an international network. As a Fulbright postdoctoral scholar at the Eindhoven University of Technology, Harold rubbed shoulders with all of the giants of chromatography, including A.J.P. Martin, J.J. van Deemter, and Marcel Golay. Harold had many amazing stories about his interactions with notable scientists and engineers. And, during his professional career, Harold traveled often, especially to Europe and South America. He was especially keen on trying to provide chromatography education and resources where it did not already exist.

I was quite envious of Harold’s international connections and wondered how I might develop something similar. So I decided I would also like to do a post-doctoral fellowship in Europe. As a result, Harold sought out and met with Wolfgang Lindner, who was looking for a new researcher, at an HPLC conference. I was able to go to Vienna and visit with Professor Lindner after my first trip to Riva del Garda, Italy, for the International Symposium on Capillary Chromatography in 2002. I ended up spending over two years in Lindner’s lab and made so many friends and colleagues during this time – relationships that have remained throughout the years.

Palmer: Harold understood that, at its core, scientific research is a human endeavor; that progress is built on scientific understanding and prior results, but also on strong interpersonal relationships with a foundation of mutual respect and understanding. He built an international network of true friends and collaborators by showing great interest and respect for the scientific and personal interests of others, regardless of nationality or background.

Sandra: Harold selflessly shared the contacts he made with important figures in our field. For example, my friendship with Fasha Mahjoor, founder and ex-CEO of Phenomenex and founder/CEO of Neoteryx, is based on a spontaneous visit by Harold and Fasha to the Research Institute for Chromatography in the early nineties.

Remcho: Most of my very favorite times with Harold were on the road. Throughout the 70s, 80s and 90s, he routinely took small groups of graduate students to conferences in Latin America and Europe. What a great way to educate young people: connecting them with scientists from all over the globe. On my first trip to Europe with Doc, we flew into Munich and rented a car for a multi-stop lecture tour that culminated with a conference. We climbed into the rental car at the airport, and he found a news station on the radio. We listened to talk radio for about an hour so that he could “tune up” his language skills, and from there it was 100 percent German. Well, until it was Italian, Spanish, Dutch, or...

Schug: Most of all, Harold taught me to be kind and considerate. No one should be considered better than someone else. Embrace diversity, as it is the spice of life – the window to other cultures and ways of thinking. And perhaps most importantly, always pay it forward.

Palmer: We can all learn from Harold’s grace when interacting with others; to listen carefully and be willing to learn, to show true interest and respect, and to sincerely congratulate others for their successes.

Dugo and Mondello: We learned that one can be a good professor, internationally well known and appreciated, while continuing to enjoy life, family, and friends. Regarding his book, we think that every chromatographer worth their salt – beginner or expert – must have a copy on the shelf. We are very lucky to have a copy signed and dedicated to us.

Remcho: What do Harold’s skills tell us about what it takes to be a teacher, professor, and mentor? It would be easy to say, “A really great teacher needs to be smart” – because he was incredibly smart. Or: “A really great Professor needs to be internationally recognized,” – because he was. Or: “A really great mentor needs to be observant,” because Harold was definitely observant. What really set him apart though, at least to me, was that he really, truly loved people. He wanted those around him to feel comfortable, cared for, appreciated, and valued. What kind of skill makes a person competent in that way? I suppose today we would call it EQ, emotional intelligence. Harold McNair had a super high EQ – it was off the charts.

And damn, he really could dance.