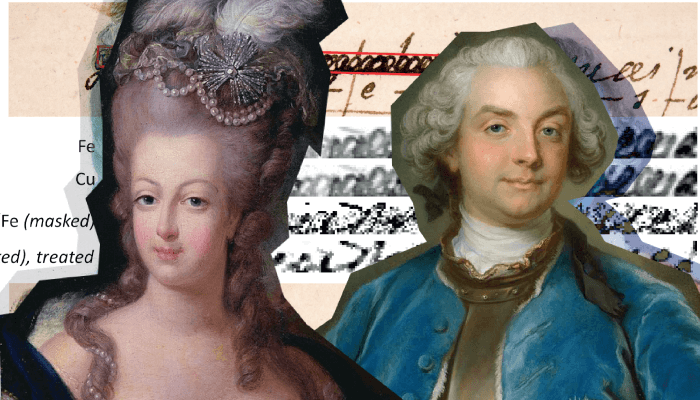

It’s the height of the French Revolution. You, the wife of King Louis XVI, are currently under house arrest and desperate to speak with your (rumored) Swedish lover – Count Axel von Fersen. You decide to write to him again, risking a tender phrase: “You that I love and will love until…”

Years later, this sentence – among many other affectionate words and passages – would be scribbled out by an unidentified censor. But this is just one example of the many secret letters the pair would send between 1791-1792. In total, over 50 have been kept in the French National Archives – 15 of them with heavy redactions. The key challenge? The fact that a similar dark ink has been used to either cross out or cover sections with looping letters; many other analytical techniques simply failed to distinguish the inks and produce readable text. But now, after more than 200 years, we are finally getting to the bottom of the story – all thanks to advanced X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy.

Specifically, Anne Michelin and her team from the Centre de Recherche sur la Conservation were aided by the development of more accessible mobile systems for XRF analysis – like the Bruker M6 Jetstream XRF scanner used in this study.

XRF was used to analyze the composition of both the original and censoring ink and create a map of the different elements present. Data processing tools were then used to compare and contrast, increasing the legibility of the writing.

Among the discoveries, which included such intimate language as “madly,” “beloved,” “adore,” and “tender friend,” the team uncovered evidence that it was von Fersen himself who tried to keep the true meaning of the letters hidden. Previously, historians had surmised that it was a great-nephew who had censored the texts to protect the family’s reputation...

So far, eight of the redacted letters have been successfully analyzed – and we will have to wait a while longer to see what the other seven say. But there is no denying that such an analytical approach could have a significant impact on future cultural heritage studies.

References

- A Michelin, F Pottier and Christine Andraud, Sci Adv, 7 (2021). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abg4266