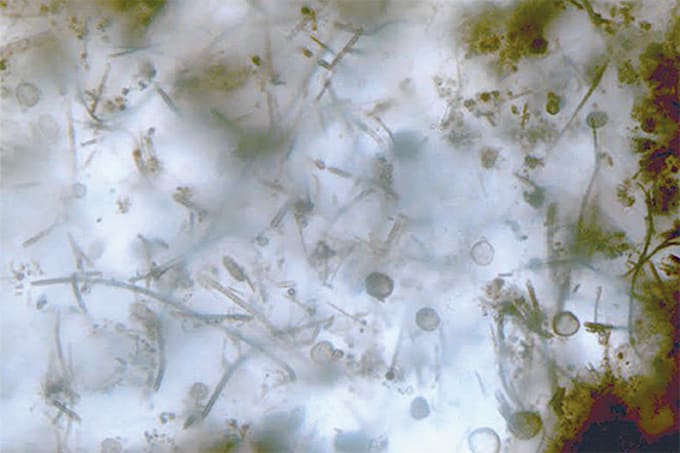

Fossilized faeces from a large fish with spiral gut (hence the spirals in the coprolite), showing fish scales indicative of diet.

Credit: Martin Qvarnström

Analyses of hundreds of fossilized digestive remains has revealed details about the dietary habits and ecological strategies that enabled dinosaurs to dominate terrestrial ecosystems. By studying more than 500 bromalites – fossilized faeces, intestinal contents, and vomit – scientists uncovered how dinosaurs gradually replaced other tetrapods, leveraging both opportunistic advantages and dietary adaptations during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods.

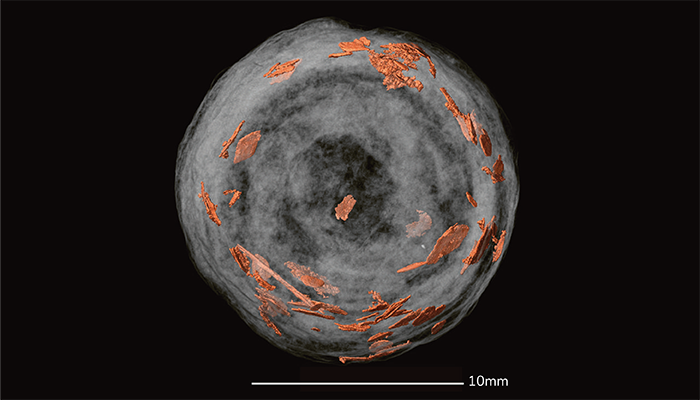

An international team of researchers, led by Uppsala University in Sweden, employed synchrotron microtomography and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) to analyze bromalites, reconstructing three-dimensional models and identifying microscopic dietary remains, such as beetle exoskeletons, fish scales, and plant cuticles. Molecular analyses further revealed compounds like sterols and short-chain alkanes, highlighting rapid mineralization and exceptional preservation.

The findings indicate a stepwise ascent of dinosaurs to ecological dominance. Early dinosauriforms, such as Silesaurus, played limited roles in Late Triassic ecosystems, sharing their habitats with other tetrapods, including rauisuchians and dicynodonts. However, climate-driven shifts in vegetation and the extinction of less adaptable species created opportunities for dinosaurs to expand their niches.

The team’s detailed analyses of bromalites provided direct evidence of these transitions. For example, coprolites linked to Silesaurus contained both insects and plants, reflecting its omnivorous diet. In contrast, bromalites from large predators like phytosaurs and rauisuchians revealed fish remains, underscoring the interconnected nature of terrestrial and aquatic food webs. Meanwhile, plant-rich coprolites from herbivores such as dicynodonts highlighted their dependence on conifers, a dietary specialization that may have limited their adaptability to changing environments.

“The research material was collected over a period of 25 years. It took us many years to piece everything together into a coherent picture,” said Grzegorz Niedźwiedzki, researcher at the Department of Organismal Biology and the study’s senior author, in a press release. “Our research is innovative because we have chosen to understand the biology of early dinosaurs based on their dietary preferences. There were many surprising discoveries along the way.”

The study also uncovered how dietary flexibility helped dinosaurs thrive. Fossilized plant material from early Jurassic herbivorous sauropodomorphs showed evidence of charred vegetation, suggesting that these animals might have ingested burnt plant matter to detoxify their diets. This adaptation coincided with an increase in bromalite diversity, signaling broader ecological strategies among dinosaurs.

“Unfortunately, climate change and mass extinctions are not just a thing of the past. By studying past ecosystems, we gain a better understanding of how life adapts and thrives under changing environmental conditions,” says Martin Qvarnström, researcher at the Department of Organismal Biology and lead author of the study. “The way to avoid extinction is to eat a lot of plants, which is exactly what the early herbivorous dinosaurs did. The reason for their evolutionary success is a true love of green and fresh plant shoots.”