Though a taboo topic for a long time, many in the art analysis world are starting to open up about how they deal with inauthentic art. In a recent exhibition, the Museum Ludwig has revealed the results of a systematic investigation of over 100 paintings from the Russian avant-garde – a movement well known to be afflicted by forgeries. Visitors to the museum can gain an understanding of the techniques employed to study these works, including infrared and X-ray imaging, fabric tests, and pigment and binding media analyses.

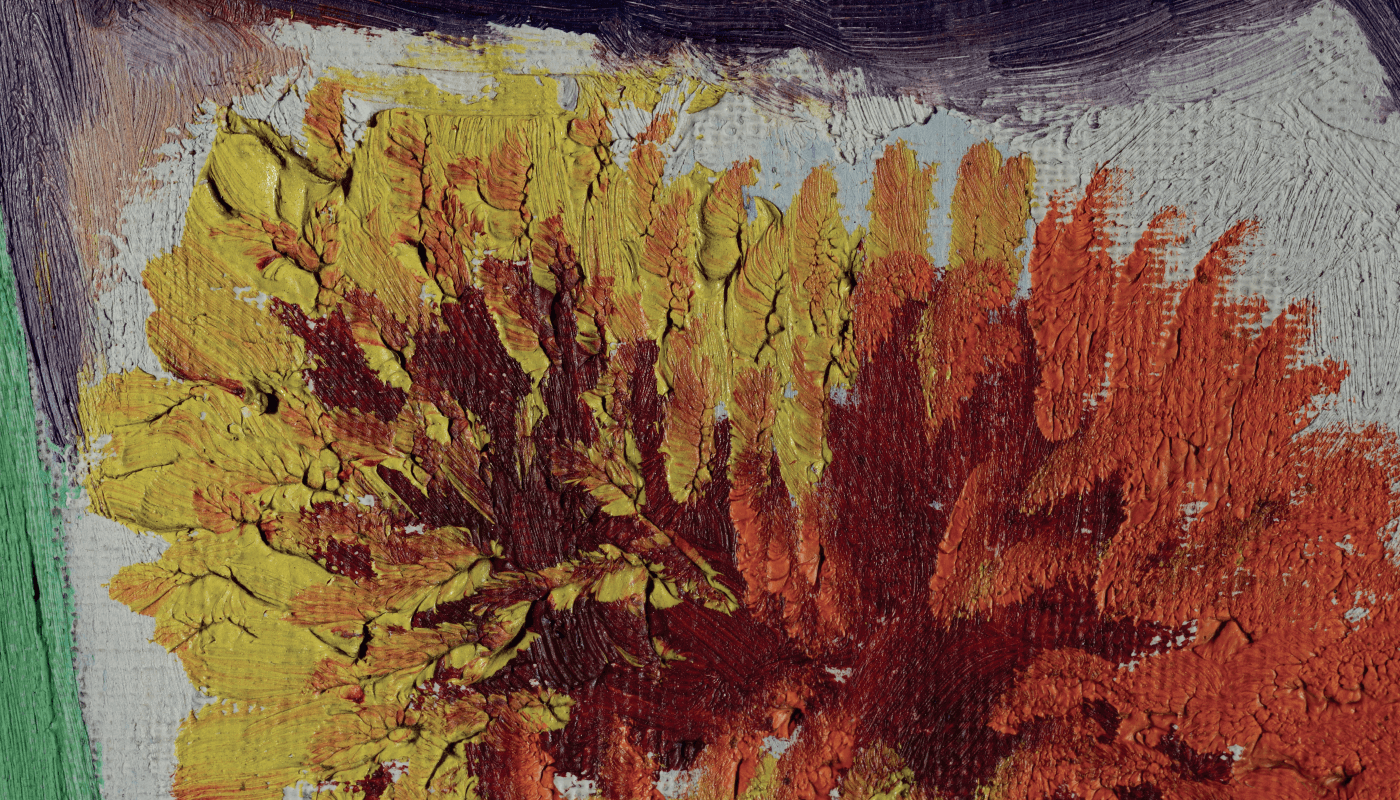

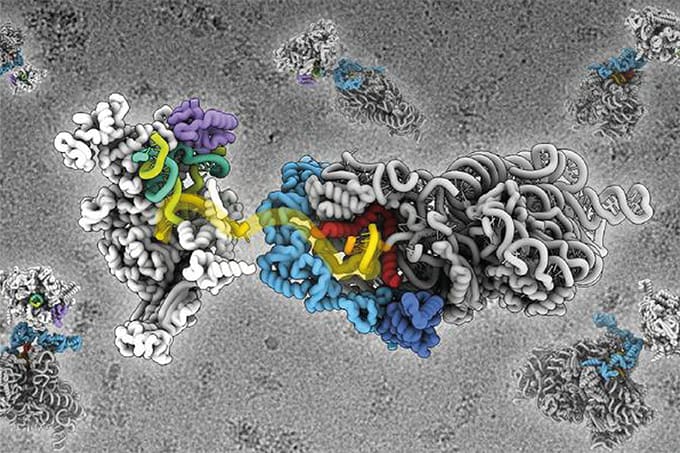

Funded by the Russian Avant-Garde Research Project (RARP), Jilleen Nadolny and her team at ArtDiscovery (previously Art Analysis & Research) examined 14 of the paintings by prolific artist-couple Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, to build a detailed body of technical information against which forgeries can be compared – thus securing the art market. Their multi-analytical approach includes identifying pigments by Raman microscopy, elemental determination by SEM-EDX, and particle morphology by polarized light microscopy.

“There is a growing need for evidence-based information in the art market; though art has long been assessed in terms of provenance and connoisseurship, art analysis provides vital evidence to support these forms of assessment,” says Nadolny. Forgeries are often given away by the presence of anomalous materials invented after the time the object should have been made. “Technical imaging reveals information about reused supports – a common forger’s trick is to make a painting look older by reusing earlier works – while other forms of analysis like radiocarbon dating allows us to discern a more precise provenance,” says Nadolny.

But art analysis is not only useful for uncovering fakes, it can also help recognize and validate authentic works, to understand them more fully and enable better preservation in the future. “Through analysis we can learn about all aspects of the material object: condition, original materials and techniques, restoration history and physical alteration of materials, and even how the artist actually worked,” adds Nadolny. “Many specialists, from art historians to conservators to lawyers arguing authenticity cases, will use our information – each in a different manner.” Some interesting findings from the team’s analysis included discovering hidden images that had been painted over by the artists, re-dating some of the works using data on the materials identified, and the surprisingly widespread use of underdrawings by the pair.

The hope is that such studies will be further encouraged – not only to help minimize risk in the international art market, but also to better inform our understanding and conservation of art for future generations.