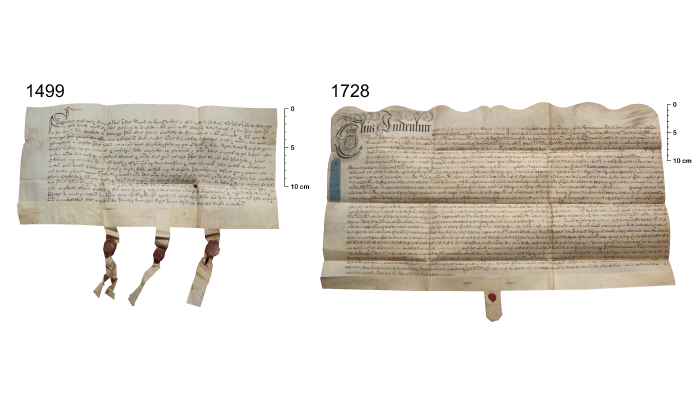

Though historic legal deeds are abundant in British archives, they are also largely neglected as a resource. “In 1925, a change in the law meant that old title deeds (documents detailing ownership of property) no longer needed to be kept,” says Sean Doherty, lead author of a recent paper exploring the use of sheepskin parchment in early modern legal deeds. “Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, were destroyed. However, these documents are fantastic biological archives, through which millennia of animal genetics, breeds, farming, craft and trade can be explored!”

But identifying the animal used for a manuscript can be challenging – previous approaches look at characteristics like color, texture or follicle patterns on the skin, but these are subjective and often inaccurate. To find out more about the animals used for their production, Doherty and his team turned to “ZooMS” (zooarchaeology by mass spectrometry) or, for the uninitiated, peptide mass fingerprinting – in this case, using a MALDI-TOF instrument (Bruker Daltonics) and an open source MS software tool (mmass.org).

“ZooMS offers an objective identification based on proteins extracted from the skin,” says Doherty. “Previous analyses have established peptides that are specific to species, so we can look for these markers and make a determination.”

The team analyzed over six hundred documents and found almost all were made of sheepskin. They believe the preference for this material may be down to the unique structure of sheepskin: “Parchment is made from dermis, a layer of skin which is divided into two parts,” says Doherty. “There’s the fine dermal fibers of the upper papillary dermis and the larger fibers of the lower reticular dermis. In sheepskin, the join of these two layers is weak because of an abrupt change in structure and a large quantity of fat, which forms at the junction. During the production of parchment, the skin is submerged in an alkaline solution which draws out this fat. In sheepskin, which has more fat than calfskin, goatskin or deerskin, this process has the potential to leave voids between the two layers. If the surface of the parchment is scraped in an effort to remove or alter text, these two layers are likely to detach – known as “delamination” – leaving a large blemish on the surface.” Essentially, the structure makes it difficult for anyone to fraudulently alter a legal document.

Looking ahead, the team wants to employ stable isotope analysis to examine the geographic origin of the skins and even gather information on the sheep’s diets. “These documents cover a period often called the ‘Agricultural Revolution,’ so we are looking to examine the introduction of new crops, manures, and farming practices which may be recorded in the skin,” adds Doherty. “There is so much information behind the text!”

References

- S P Doherty et al., Herit Sci, 9, 29 (2021). DOI: 10.1186/s40494-021-00503-6