I am approaching my 80th jubilee in a few months, and I believe it puts me in a position to fairly and critically evaluate the years spent in the presence and absence of the “Iron Curtain” – years that have gone by sooner than I expected. In 1957, I was fortunate to be selected for the very first group of Soviet students delegated to the German Democratic Republic to complete our chemical education. I graduated in 1962 from the Technische Hochschule in Dresden, which gave me broad chemical knowledge and some command of the German language (as well as a few key English phrases).

On returning to Russia in the 1960s, I joined the Nesmeyanov-Institute of Organoelement Compounds (INEOS) in Moscow for my PhD studies. I quickly understood that in Russia, with very little modern equipment, I had to be inventive if I wanted to be successful.

Two big ideas

In an attempt to separate two enantiomers of amino acids by liquid chromatography on a chiral ion exchange resin (that I prepared by binding chiral proline on polystyrene beads), I introduced copper (II) ions into the chromatographic system in 1968. And that was the beginning of what proved to be a very successful technique – chiral ligand exchange chromatography (CLEC). Later, the principle of CLEC served as the technique of choice for developing two-dimensional LC, chiral capillary electrophoresis, chiral preparative simulated moving bed (SMB) techniques and others. The keen interest in CLEC amongst specialists in the fields of chromatography, general stereochemistry, asymmetric organic synthesis, pharmacology and polymer chemistry gave me the unique opportunity of lecturing at numerous international meetings. I was able to visit many interesting countries and develop friendships with outstanding scientists – readily supported by both the organizing committees of meetings and the Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Though the principle of CLEC was ‘protected’ in 1969 by several international patents assigned to my state, we did not benefit from any of the chiral stationary phases that a series of Western companies brought to market – the USSR was simply not equipped for international court debates. Though totally unprepared for any kind of business activity myself, I was pleased to see Regis Technologies offering “Davankov’s columns” for enantiomeric resolutions of complex-forming compounds, such as amino acids... My lab and I also worked on another important idea: preparing nanoporous polymeric adsorbing materials by intensive crosslinking of linear polystyrene chains in solution. The key was to introduce many rigid struts between the chains, thus converting the initial solution (or soft gel) into a rigid open-work material with a huge effective surface area – in the order of 1000–2000 m2/g. Twenty years later, hypercrosslinked polystyrene adsorbing materials appeared on Western markets, manufactured in the hundreds of metric tons for the purification of water, isolation of valuable components, removal of odors from gas streams, and so on. While monitoring natural and industrial waters, analysts often use small solid phase extraction (SPE) cartridges with polymeric adsorbing materials, but most don’t know the details of the sorbent. Even fewer know that the polymer can be made in true nanoporous form, thus functioning as a restricted access material (RAM) for direct extraction of small molecules, while rejecting bigger ones. Even specialists do not yet appreciate that neutral nanoporous beads can be successfully used for direct separation of mineral ions with an unprecedented self-concentration of isolated components. Still, we are pleased that we succeeded in developing hypercrosslinked polymeric hemosorbents, which have already saved the lives of many patients with sepsis and septic shock.No regrets

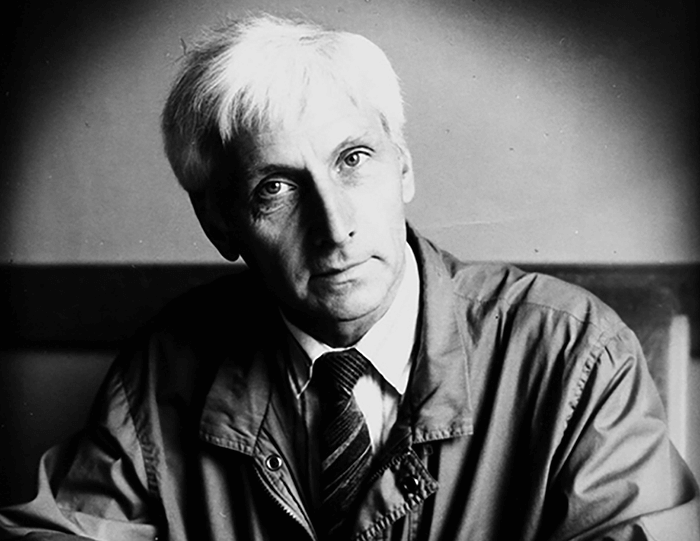

Reflecting on the years behind the Iron Curtain, I can state that I would not radically change anything in my scientific or personal life. As a scientist, I would not have been able to influence, much less change, the political situation from behind the walls of INEOS, where I have now worked for 55 years. During the first half of that period, the Institute belonged to the Academy of Sciences of the USSR; thereafter, it belonged to the Russian Academy of Sciences. It is impossible not to notice the difference between the attention paid to basic science in former times, and the “permission to earn money by ourselves” that we have gained since we’ve become “open to the world.” There is and never was sufficient research money. But we used to have a stable budget; nowadays, our state has reduced basic financial support dramatically. A large portion of the funding available is now being distributed via various foundations, but the evaluation of proposals is far from fair. As a result, the funding success of research groups often has little to do with their scientific productivity. More regrettable still, we are overloaded with writing endless plans, evaluations and reports, so that I no longer find it enjoyable to be Department Head. And there are no younger scientists to replace me; of the many PhD students whose work I had the pleasure of initiating and supervising, not one can afford to continue a scientific career at INEOS.I joined the Communist party of the USSR rather late, when Brezhnev announced “collective leadership” in the party. My party membership has not damaged my reputation at INEOS, demonstrated by the fact that, when permitted to elect a new director, our staff nominated me three times for the position (though it was never approved by ‘democratic’ academy chiefs). Before the fall of the Iron Curtain, I was twice elected to the position of first bureau secretary of INEOS, something that allowed me to participate in all the important decisions in the life of the institute, in close cooperation with the director of the institute (Nesmeyanov) and the chairman of the local trade union. After 1989, this ‘totalitarian’ tradition was abolished, and our staff appear to be helpless to oppose the dictates of appointed bureaucrats. Looking back over my life, I realize it has been full of activity and interesting events – irrespective of the Iron Curtain. Though traveling much less in later years (mostly because of the lack of financial support from the Russian Academy of Sciences, but also difficulties in obtaining a Schengen visa), I have enjoyed an active and often successful career at INEOS – as well as the respect of my colleagues and the love of my nearest and dearest who, thank God, stayed in the homeland with me. Vadim Davankov is Professor and Head of the Laboratory for Stereochemistry of Sorption Processes, Nesmeyanov-Institute of Organoelement Compounds, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow. He was born on November 20, 1937 in Moscow, and followed in the footsteps of his parents by studying at the Mendeleev Higher School for Chemical Technology. He later graduated from the Technische Hochschule Dresden, and there, despite the recommendations of USSR Embassy officials, married a Greek woman, Evtichia. He joined the Nesmeyanov-Institute in Moscow as a technician in 1962, gained a PhD and DrSc, and became a full professor in 1980. He is the proud recipient of numerous awards, including the State Award of Russia (1996), Distinguished Scientist of Russia (2005), Kargin Award in Polymer Chemistry (2017), Chirality Gold Medal (1999), Martin Gold Medal (2005), Molecular Chirality International Award (2010), M. Tswett & W. Nernst Separation Science EU Award (2010). He has two sons, six grandchildren and one great-grandchild.