Lloyd Snyder has received national and international recognition for his wide-ranging contributions to chromatography, especially HPLC. He has twice been recognized by the American Chemical Society and received The Lifetime Achievement in Chromatography Award from LCGC magazine in 2012. “I first encountered gas chromatography in 1955, then switched to liquid chromatography in 1957, and HPLC, the premier technique for chemical analysis, in 1966,” he recalls. Snyder, who recently retired after a research career that spanned 60 years, spent his entire career in industry; the first half at four different companies, and the second at LC Resources, which he co-founded in 1984. During that time he authored or co-authored over 300 publications and nine books.

I have been involved with industrial research for almost 60 years, and I still recall the first time I set out to submit a paper for publication. The response from management was: “If this stuff is really important, why are we giving it away to our competitors? And if it isn’t really important, why would you want to publish it?” That nicely summarizes the quandary I want to address here.

As an industrial researcher, there are various reasons or incentives to proceed with publishing a paper, reflecting the interests of both the author and the company. The considerations are comparable to whether to visit the bathroom or not: it starts with an urge, after which timing and location are critical. In the case of publishing, the timing of submitting a paper will often be determined by the importance of confidentiality, and the place (that is, the company where the research was carried out) may be a dominant consideration. Let’s look at these three parts of the question.

Publication might be driven by a desire to:

- Share information with the scientific community

- Enhance professional status

- Promote a particular idea, product or procedure.

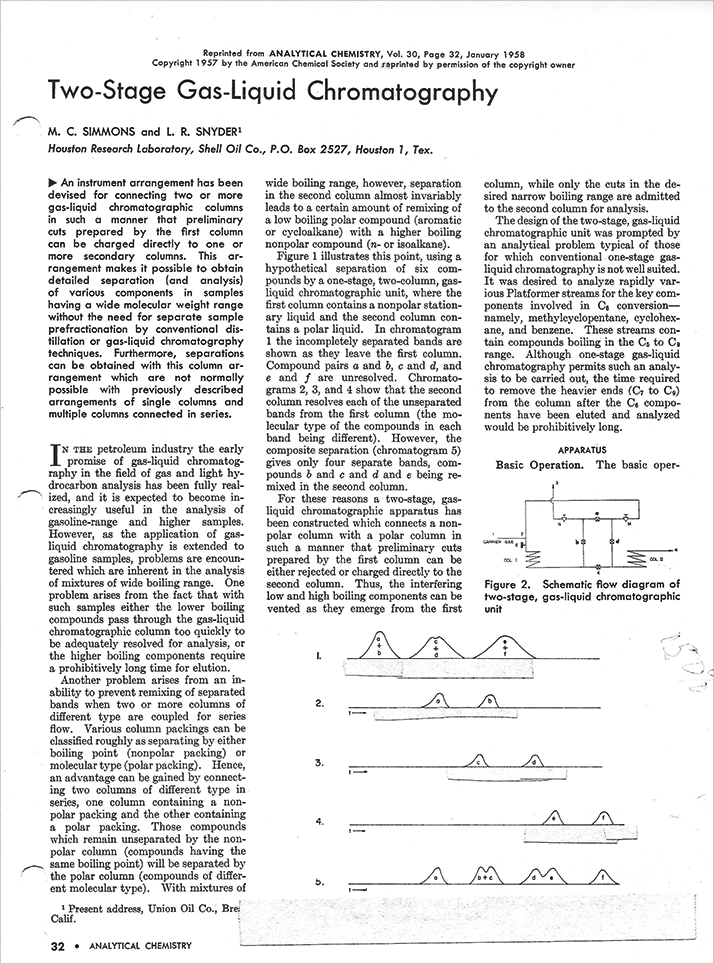

The first consideration is: wait until the fruit is ripe. I mentioned that my first paper in industry was initially turned down by management. When permission was finally granted a few years later, a much better paper could be – and was – written (presented opposite). Publication in an industry setting must also consider the competitive value of research results, and the need to exploit this information before competitors get hold of it. When patenting is appropriate, the work can be published within a year of a patent application. In other cases, it may be necessary to delay publication for a longer period. However, both the author and company should keep in mind that potentially publishable work cannot be kept hidden indefinitely. Publication might also be delayed while the author ponders the next step in a research program. This is akin to picking all the fruit before the birds and squirrels arrive. Academics also want a leg up on their peers when opening up a new line of research, which argues against overly rapid publication by them. Where was the work carried out? Publication policies vary widely among different companies, usually for valid reasons. My company sold software to customers who needed to:

- Understand how it worked

- Have confidence in its accuracy

- Perceive its potential value

I worked in industry for almost six decades. The first half was spent with four different companies, and the second half with my own company. Over the entire period I usually enjoyed both the time and resources to pursue ideas relevant to the raison d’etre of each company. Often the time spent was after hours, and frequently the idea was only distantly related to company business; but if I wanted to do something, usually I could. And by being persistent and patient, eventually a way was found to get my research (or most of it) published. Do companies today offer a different response to publication than the one mentioned at the beginning of this article? More to the point, should they view research publications without the skepticism that I encountered all those years ago? I believe that the answer to this question is “yes”, for the following reasons.

Few would now argue against allowing workers as much freedom of action as possible, with an emphasis on the result and time of completion, rather than the means employed. The act of preparing a paper for publication can both enhance the interpretation of the research and lead to improved works skills. Encouraging publication should also have a positive impact on employee morale, at least for certain workers. It certainly did for me.

The prospect of publication should encourage workers to be especially open to new possibilities and/or new questions as they work. In some cases, this will suggest promising new lines of research as well as publishable results.

A company environment that is open to publication is also open to the exchange of ‘generic’ information with companies that may be competitors. ‘Generic’ information refers to ‘tricks of the trade’ that can be helpful, without seriously compromising products that are currently under development. When companies are willing to exchange this kind of information, everyone benefits. But you can’t take without giving. Publication carries this philosophy to a logical conclusion.

This is a traditional argument for allowing publication. It assumes that a certain kind of employee will be both essential to the company and motivated by the hope of publishing. When there is an excess of these people entering the job market, as at present, this argument becomes less forceful, but it would be a mistake to use the circumstances of today as a basis for tomorrow’s policy. To wrap up, work in industry followed by further research in my own company has enhanced my awareness of the role of publishing in a technically-oriented business. The benefit of writing papers was, at first, mainly that it was stimulating and personally rewarding. Later it also became a major factor in the success of our business. So, do I believe some companies should encourage publication? At a minimum the question deserves consideration, with attention to the above observations.

Lloyd Snyder is now retired and living in Orinda, California, USA.