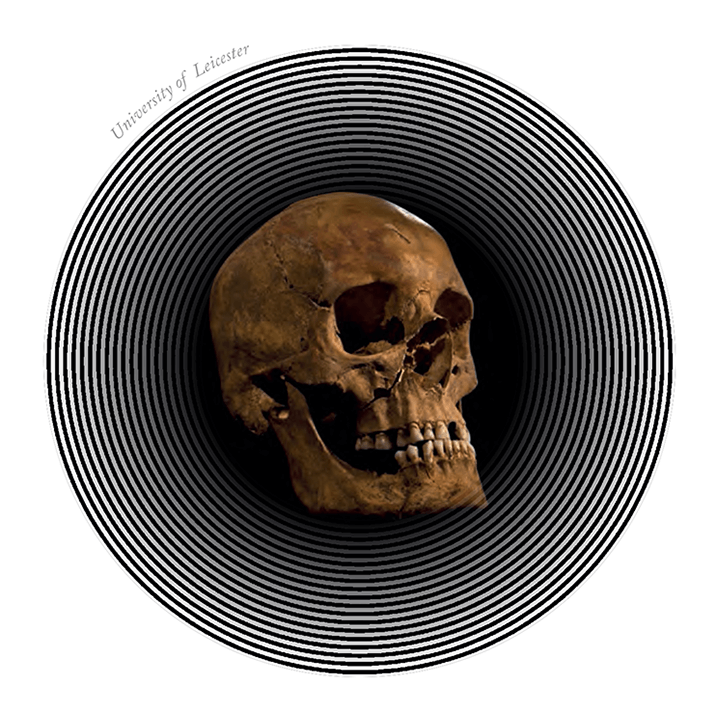

Avid readers of The Analytical Scientist will know that we’ve been following the story of King Richard III for a while. From the identification of the remains found in Greyfriars Friary Church in Leicester using DNA analysis to the use of radiocarbon dating to shed light on his eating habits. The researchers – based at the British Geological Survey and the University of Leicester – have recently published the results of the full multi-isotope analysis (1). Angela Lamb, an isotope geochemist with the British Geological Survey and lead author of the paper, tells us more.

What are the latest findings? The early isotope details came from data generated from accelerator mass spectrometry radiocarbon dating of the rib bone of Richard III, which gives an average picture of the last few years of his life. We wanted to analyze several different locations on the skeleton so that we could piece together a more detailed life history. We sequentially analyzed bioapatite and collagen from a second premolar tooth with its root intact, so that we could reconstruct Richard’s childhood and early adolescence. This is possible because oxygen and strontium isotopes are fixed in enamel biogenic phosphate at the time of tooth formation, and once fixed will not change during life. Bone, however, regenerates through life, which means that the isotopes reflect average conditions over time. As bone remodels at different rates, we chose to sample the femur (which averages conditions over the last 10-15 years of life), and the rib (which remodels faster and represents the last few years of life). By combining the data from these three locations, we were able to reconstruct Richard’s changing diet and location. Our analyses of the tooth showed that Richard had moved from Fotheringay Castle in eastern England by the time he was seven to an area with higher rainfall, older rocks and with a changed diet, which we believe is relative to his place of birth in Northamptonshire. From the femur, we could tell that Richard moved back to eastern England when he was a young adult, and had a diet that matched the highest aristocracy.

How were you able to gain such specific details? Some parts of Richard’s life are well documented, including his birthplace and whereabouts in the latter part of his life, so we were able to compare our results to these facts. There is a good match, which was very encouraging and gave us the confidence to extrapolate the data to the periods we know less about. Isotope analysis can’t tell you exactly where he was living, but by combining oxygen and strontium analysis we can suggest potential areas of the country. Similarly, diet-based isotope reconstructions can inform us about the amount of protein consumed and the types of protein, such as freshwater or marine fish. His rib oxygen isotope value is too high for someone living in eastern England, where he was known to be during the last few years of his life. Given that the carbon and nitrogen isotopes in his rib bone also suggest that he was eating more luxury foods, such as wildfowl and freshwater fish, we suggested that the high value could represent an increase in wine consumption too.

Are further analyses planned? We are not planning any further analysis on Richard III at the moment, but it has raised some questions we’d like to explore further. To our knowledge, this is the first example where the intake of wine has been suggested as having an impact on the oxygen isotope composition of an individual. Thus we’d like to follow this up with more work. We also hope this paves the way for more detailed multiisotope and multi-tissue reconstructions in the future. Read more about the analyses of King Richard III: Winter of Content (tas.txp.to/1014/Winter) A Meal Fit for a King (tas.txp.to/1014/Meal)

References

- Angela Lamb et al., “Multi-Isotope Analysis Demonstrates Significant Lifestyle Changes in King Richard III”, Journal of Archaeological Science 50, 559-565 (2014).