In the third and final installment from our roundtable on the future of sample preparation (check out parts One and Two), Marcela Segundo, Marcello Locatelli, and Stig Pedersen-Bjergaard respond to questions from the audience – exploring how to balance precision and environmental responsibility, the challenges of regulatory acceptance, and whether we’re heading toward truly “sample prep-free” analysis. They also share their thoughts on education, cost, and the next generation’s role in driving the green revolution in analytical chemistry.

Read the highlights below – or register to watch the full on-demand discussion.

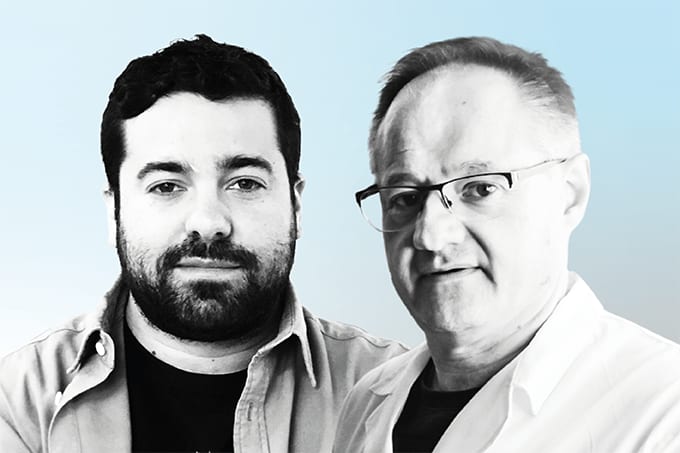

Meet the Experts

Marcela Segundo is Professor of Analytical Chemistry at the University of Porto. She led the Analytical Development Group at the Portuguese Government’s Associate Laboratory for Green Chemistry, Clean Technologies, and Processes from 2018 to 2024, and currently heads a group pioneering greener, automated approaches to sample preparation. In 2016, she received the FIA Award for Science for her contributions to sustainable analytical methods.

Marcello Locatelli is Associate Professor of Analytical Chemistry at the University of Chieti-Pescara in Italy. His work focuses on innovative extraction techniques and sustainable bioanalytical methods, with applications spanning clinical, pharmaceutical, food, and environmental analysis.

Stig Pedersen-Bjergaard is Professor of Analytical Chemistry at the University of Oslo and holds a part-time post at the University of Copenhagen. He’s internationally recognized for developing liquid-phase and electromembrane extraction techniques – green sample preparation methods now used worldwide.

Since the main challenge in sustainable analytical chemistry – or sustainable sample preparation – is balancing analytical quality with reducing environmental impact, what should we choose if forced to decide: better results or less harm?

Segundo: Well, it’s not such an obvious choice. We all want the most reliable analytical results – but we also have to think about the bigger picture. Rather than focusing only on sample preparation, I prefer to think about the entire analytical process. In my lab, for example, we’re developing screening methods that require minimal sample preparation – just enough to determine whether the target analytes are present. Then, if needed, we’ll move on to more complex methods and sample treatment.

Locatelli: From an analytical point of view, our main goal is always to obtain accurate, reliable, and reproducible results – results that can be trusted in any context, whether pharmaceutical, environmental, or even legal. However, I also believe we can often find a third way. In situations where we might have to choose, we should first ask whether it’s possible to adapt or modify the procedure so that we achieve the required data quality while still adhering to the principles of green analytical chemistry and sustainable sample preparation. But, of course, that’s not always possible.

Pedersen-Bjergaard: For any analytical measurement, we need to define the minimum required data quality – the level of precision and accuracy necessary for the purpose. If we can achieve that using a green method, we should absolutely go for it. But if a sustainable method can’t yet meet that required standard, then we still need to rely on traditional methods.

If you had to pick a single biggest obstacle to the wider adoption of greener, more sustainable sample preparation methods, what would it be?

Segundo: I would say the biggest obstacle is regulatory demands, as we discussed in Part Two. I really believe it’s the main hurdle we have to overcome before new methods can be more widely adopted.

Pedersen-Bjergaard: I see it as a combination of obstacles that come together. First, the official methods themselves are not green. Second, changing methods is expensive – both in time and resources. And third, laboratory managers tend to be conservative; they’re understandably cautious about altering validated procedures that already meet compliance standards. That said, this will gradually change as the next generation takes on leadership roles. When younger scientists – who care deeply about sustainability – become the lab managers and method developers, they’ll drive adoption forward. But even then, cost will remain a barrier, so the transition will take time.

Locatelli: I’d add that sustainable sample preparation methods often require more development time initially, and in many cases, it’s not easy to establish new standardized procedures that can be easily implemented in laboratories. Many of these new methods also demand specialized training, or at least more time for operators to become comfortable with them. In contrast, the existing standard methods are well known, quick to perform, and already validated – so even if greener methods are better in principle, it can be difficult to convince laboratories to switch.

Are the current greenness assessment tools fit for purpose? Do they go far enough?

Locatelli: There are now many greenness assessment tools available, and they all work well within their intended scope. However, I don’t think it’s possible to have a single “gold standard” tool – one that can address every question or evaluate every aspect of the analytical process and sample preparation equally well.

In practice, combining different tools provides the most complete and reliable evaluation of a method’s sustainability. I’d say that the current tools are well developed, ready to use, and accessible even to young researchers who are just beginning to work in this field.

Pedersen-Bjergaard: Yes, I agree with Marcello. The current greenness assessment tools are good – they’re functional and useful – but they each take slightly different approaches. In the future, I think it would be valuable to combine the strengths of different tools into a more unified or flexible platform. Such a platform should also allow researchers to refine or update assessment criteria over time while still being able to compare with older evaluations. It would be ideal if we could eventually agree on one standardized framework that everyone could use.

Segundo: I agree – standardization is urgently needed. New greenness metrics seem to appear almost every week, and many are focused on specific parts of sample preparation. We need to think about how we can apply these tools. In my experience, different people can reach very different conclusions simply because they interpret the same criteria in different ways. Standardization – both in the tools themselves and in how they’re taught and applied – would help ensure consistency and reliability across studies.

Locatelli: The current tools are well suited to today’s technologies, materials, and procedures. But as new materials, methods, and instruments emerge, these tools will need to evolve. They’ll either require updates or, in some cases, entirely new frameworks to stay relevant and effective.

We’ve heard a lot about greener and more efficient sample prep – but what about sample prep-free methods? Are we realistically moving toward analyses that can skip preparation altogether?

Pedersen-Bjergaard: Typically, an analytical method involves three main steps: sample preparation, chromatography, and mass spectrometry. From my perspective, sample preparation has evolved over several decades into a very green and efficient stage of the process – we can now perform it using very small amounts of chemicals, consumables, and organic solvents. I’d say that chromatography and mass spectrometry are behind sample preparation when it comes to greenness and sustainability.

We need to maintain the specificity of our assays – and we can achieve that in two ways: through highly optimized chromatography and mass spectrometry, or by building that specificity directly into the sample preparation step. Since sample preparation has now evolved into a set of very green, efficient techniques, I believe we should take the opposite approach to what the question suggests. Instead of eliminating sample prep, we should capitalize on its strengths – leveraging green sample preparation to deliver the necessary specificity, and then simplifying the final measurement using smaller sensors or far less instrumentation than we typically rely on today with chromatography and mass spectrometry.

Locatelli: It’s a great question, and I think the answer really depends on the analytical requirements – sensitivity, selectivity, and the type of analysis being performed. For example, with advanced LC-MS platforms, we can often use dilute-and-shoot procedures, where little or no sample preparation is needed. But that approach isn’t always viable. Sometimes we need to preconcentrate the analytes or remove interferences to achieve robust quantitative data. So yes, we are moving in this direction, but it depends on the target of our method.

Segundo: I’m thinking more about sensors. There’s been a lot of exciting research in this area in recent years – it’s a hot topic. When you build a sensor, you can, in some cases, integrate sample preparation directly into their design.

If you’re using state-of-the-art chromatographic or mass spectrometric systems, it’s still difficult to imagine skipping sample prep entirely. The cost of the instruments and the risk of contamination make that unrealistic. No one wants to damage expensive equipment by running untreated samples.

So I’m going in the same direction as Stig mentioned – thinking about sensors – and it also connects back to the first question. I believe the best approach might be to combine the two ideas: using sensors that aren’t necessarily comprehensive or capable of distinguishing every class of analytes, but that can serve as an initial screening tool. If the sensor result is positive, then you can invest the time and resources in a more comprehensive, state-of-the-art analysis.

Any final thoughts – are you optimistic about the future of sample preparation, both in terms of general innovation and the move toward more sustainable approaches?

Locatelli: From my side, I’m completely optimistic. As Stig and Marcela highlighted, we already have the knowledge, the instrumentation, the materials, and an active, growing research community in this field. At the same time, we have a kind of mission, as Stig mentioned in Part One – to teach the concepts of sustainability and green analytical chemistry at universities.

If we equip the next generation with these principles early on, they’ll be ready to build on what we’ve started, developing new materials, new methods, and new ideas. Education is absolutely key – it must begin at the university level, and ideally even earlier. By introducing these ideas at different stages of education, we can shape the scientists of tomorrow.

Segundo: Yes – but with one important caveat: cost. It’s something we haven’t talked much about today, but it plays a huge role. In real life, people often make choices based not just on conscience but also on budget. So if we want sustainable methods to be widely adopted, we must ensure they’re also affordable and competitive.

I’m optimistic if we can keep that balance in mind – offering green alternatives that are also practical and cost-effective. One example I’d like to mention, which we didn’t discuss earlier, is supercritical fluids. They once held great promise for green sample preparation, but we don’t see them as widely used today as I’d hoped. I think revisiting and re-evaluating such technologies could help us move closer to true sustainability.