A group of windows from Canterbury Cathedral may be the oldest stained glass windows in England, according to a team of scientists from University College London and conservators from Canterbury Cathedral (1). The researchers used X-ray fluorescence spectrometry – specifically, a portable version of the technique, customized with a 3D-printed attachment – to date the windows. We spoke with the lead author of the study, Laura Ware Adlington, to find out more.

I am a specialist within the field of archaeological materials science, which uses techniques from materials science and chemistry to study archaeological and cultural heritage materials. We use these approaches to study when and where things were made, but also the wider systems of technology and production, innovation and knowledge transfer, trade and exchange, and how things were used, reused and discarded. All of this is deeply entrenched in the study of the human past – based upon the idea that humans both shape and are shaped by the material world, and so, by studying material culture, we can study people. My specialism is in glass, with a particular focus on medieval stained glass, but I've also worked on various metals and ceramics.

The panels I ultimately worked on were removed from the cathedral walls as part of emergency conservation on the stonework, which provided an opportunity for the public to see them up close in exhibitions and for specialists to study them more easily. I was working on glass from York Minster as part of my PhD and wanted to test the noninvasive technique I’d developed there on a separate case study. Fortunately, Leonie Seliger – director of the stained glass conservation studio at Canterbury Cathedral – was interested!

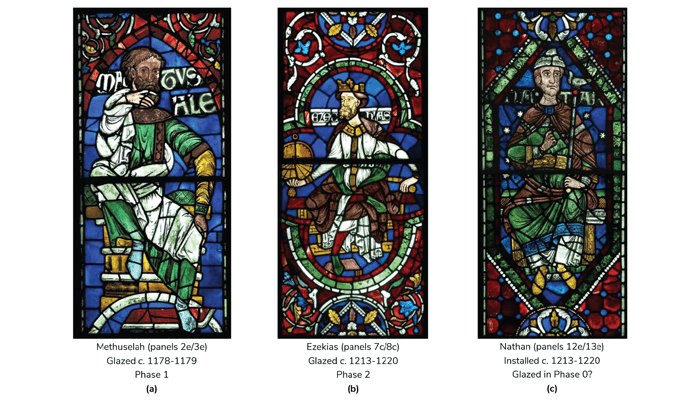

The early stages of the data analysis were particularly labor-intensive for this project. The panels have had a complicated history, so every piece of glass had to be scrutinized to ensure that the chemical data, the style of the paintwork, and its position in the panel all agreed with the hypothesis.

The windows were dated using two lines of evidence that ultimately agreed. First, in the 1980s, Madeline Caviness wrote an article arguing that the stylistic characteristics of some of the panels indicated an earlier origin. We then used an analytical technique called X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, which measures elemental composition. We used a portable version of this technique (pXRF), which required a customized approach that included the design of a 3D-printed attachment to enable precise, accurate in situ analysis of medieval stained glass windows. The stylistic and chemical information agreed with each other and supported the early date.

To take invasive samples of windows, the panels need to be removed from the wall and the individual pieces of glass removed from the lead strips (called cames) that hold them together. This is an expensive and laborious undertaking, so invasive sampling usually has to piggyback on planned conservation works. That’s why it was so important to develop this in situ approach. At Canterbury Cathedral, even though the panels were removed from the walls, the glass pieces were not removed from the cames, so the in situ approach was still necessary.

Honestly, yes! We could easily have had inconclusive results. The results hinged on the identification of a change in the glass source in the late 12th or early 13th century and showing that the potentially early panel predated this change in source. If there had been no change in the glass source, we would not have been able to comment one way or another. Our work at York Minster has indicated that they used some of the same glass suppliers over quite long periods of time, so it was a real possibility.

Yes, our team has more planned work at Canterbury and we are seeking funding to study panels at Pennsylvania’s Glencairn Museum.

Absolutely – but working with medieval stained glass is never dull!

References

- LW Adlington, IC Freestone and L Seliger, “Dating Nathan: The Oldest Stained Glass Window in England?” Heritage, 4, 937 (2021). DOI: 10.3390/heritage4020051.