Science is a uniquely human endeavor. But what makes humans become scientists?

About 50 years ago, high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and related techniques in separation science burst over the horizon, attracting interest from many gifted scientists. Over the next decade or so, a small cohort of scientists devoted their careers to understanding and advancing separation science – predominately liquid chromatography. The literature since then provides a history of the technical evolution of separation science, but one that is impersonal and largely ignores the many personal trials and tribulations that shaped the work. Each of these innovative individuals invested decades of their lives into advancing separation science. But what motivated them to make this choice? What hurdles did they face and overcome? These are the human challenges that we all face in our lives. And it was this largely unpublished story that the three of us began to ponder in early 2015, eventually leading us to solicit personal biographies from some of the talented scientists who were influential in advancing our understanding of HPLC.

Separation stories

As members of CASSS (formerly the California Separation Science Society, Emeryville, CA), we naturally first approached living recipients of the CASSS Award for Outstanding Achievements in Separation Science. The complete list of awardees reads like a “Who’s Who” of separation science (1). Of course, many died before the project started, including academics Calvin Giddings, Josef Huber, Csaba Horvath, Georges Guiochon, Phyllis Brown and Goren Shill, as well as industrial chemists such as Jim Little, Yoshio Kato, Walter Jennings, and Uwe Neue. But the personal stories we were able to collect provide fascinating insights. Under the authors’ impetus, CASSS has now curated and posted a collection of stories from several leading specialists in separation science at http://www.casss.org/?BIOINTRO and we expect more to come. We hope that reading these stories will prove useful to chemists looking for guidance in developing and managing their own careers. The biographies we’ve received so far certainly illustrate some key lessons for all scientists.Find your passion

Pier Righetti’s anthology begins with a recollection of his childhood in post-war Italy, including a stint as a stable hand for military mules. Later, he writes “As soon as I graduated, I got married and we left right away for the USA, the mythical land of opportunity.” His magical career moment occurred at MIT when an unnamed Japanese scientist presented a lecture on isoelectric focusing, which had been commercialized by LKB Produkter, AB. Rigetti comments: “I knew that I would embrace this methodology and grow up with it in my scientific career...” And he did, as spelled out in the rest of his biography.

Two heads are better than one

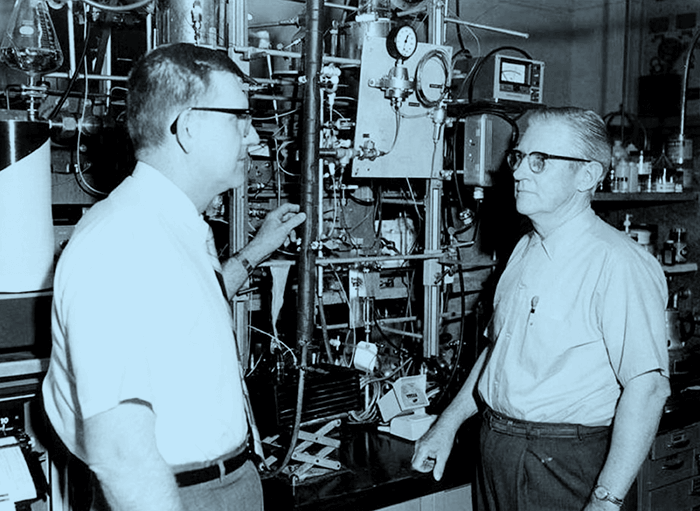

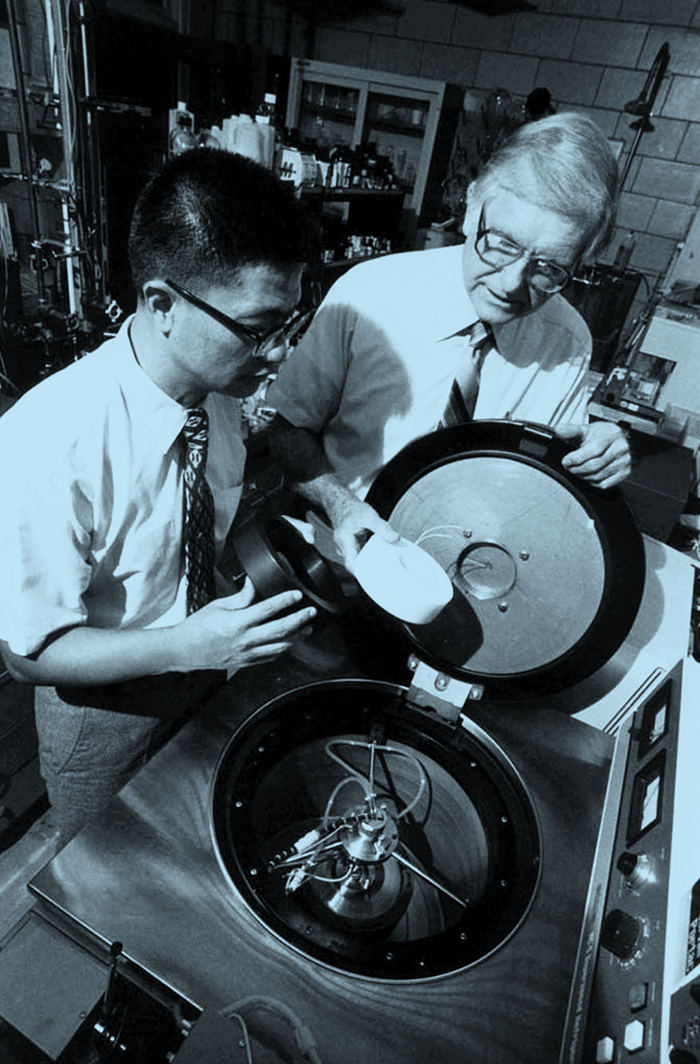

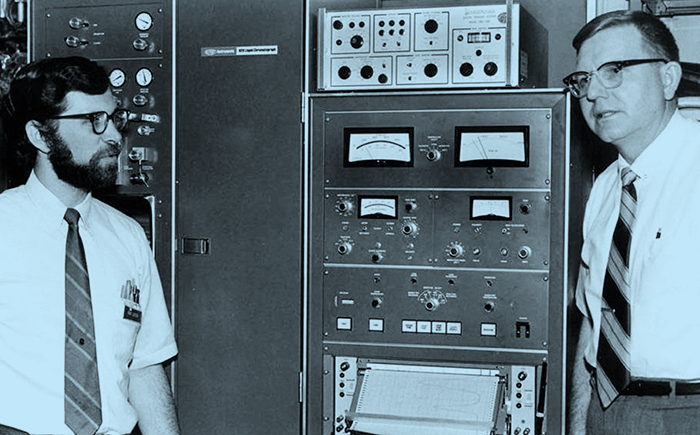

Joseph J. (Jack) Kirkland titled his contribution “Biography of an Analytical Chemist.” After a stint in the Navy, he attended Emory University and then earned his PhD at the University of Virginia. Then he joined DuPont de Nemours. In 1954, Stephen Dal Nogare introduced Jack to gas chromatography. Jack then designed and built an all-glass GC that helped him get to the bottom of several previously unsolved problems. He also extended the range of GC analytes via derivatization. Fortuitously, Jack’s lab was next to that of fellow chemist Ralph Iler, who was developing new methods to layer particles on glass plates. Jack adopted this technology to layer particles on glass beads for both GC and HPLC column packings. The resulting Zipax technology, introduced in the mid-1960s, eventually evolved into the exceptional core-shell technology that is widely used today for HPLC packings.The importance of chance

Our reading of Klaus K. Unger’s contribution is that he was not satisfied with the career prospects open to him in the German Democratic Republic, so he joined the refugee movement to the West. He navigated a complex set of circumstances to earn the equivalent of a BS degree. He entered graduate school and was assigned a project to develop novel synthetic routes to make porous silica with controlled pore structure for use in steric exclusion chromatography of proteins and synthetic polymers. It appears that the project was chosen by his advisor, with little input from Unger – a lucky gain for separation science. Unger then collaborated with Istvan Halasz to pool his knowledge of porous silica based bonded stationary phases and Halasz’s experience in instrumentation. Unger’s participation at the first HPLC symposium in Interlaken, Switzerland, was key to his acceptance as a researcher in HPLC. In return, he provided column technology that helped fuel decades of exponential growth in HPLC, starting in the mid-1970s. Today, Unger is recognized as one of the leading developers of HPLC column technology of the past several decades.Separation science continues to advance, with new problems to solve, and yet future scientists will face many similar personal and professional challenges as described in the collected biographies. Research and development can be tough – networking and dedication are essential, but so much is still governed by serendipity. Since the three of us have been fortunate enough to have interesting lives in science, we are eager to help younger scientists develop similarly successful and satisfying careers. Hopefully, the biographies we received can serve as models, highlighting both the possibilities and challenges in a career in chromatography. In the sciences, each day can present a new challenge. Rising and facing those challenges is key to making a difference in the few short years allotted to us, and eventually being able to look back with satisfaction on a life’s work. Lloyd Snyder is a Principal at LC Resources in Walnut Creek, California; Frantisek Svec lives in California and is Professor in Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Soft Matter Science and Engineering, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, China and in Department of Analytical Chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Charles University, Hradec Králové, Czech Republic; and Robert Stevenson is Editor Emeritus, American Laboratory/Labcompare, USA.

References

- CASSS Award for Outstanding Achievements in Separation Science. Available at: http://www.casss.org/?561. Accessed 27 July 2017.