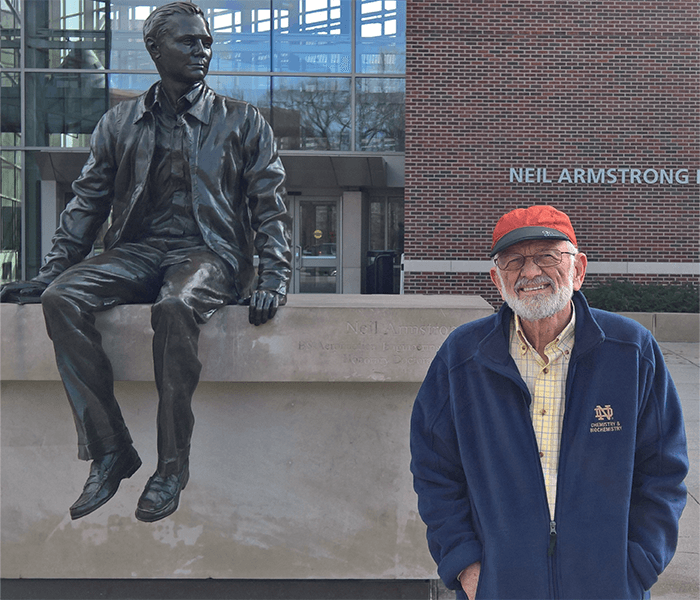

In January, The Analytical Scientist will celebrate its 10th anniversary, and we’re using the occasion as an opportunity to bring the community together and reflect on the field of analytical science as a whole. To do that, we’re speaking with leading figures and friends of The Analytical Scientist to understand how far the field has come over the past 10 years, what lessons have been learned, which memories stand out, and where we go from here. In the series’ first installment, Graham Cooks, Henry Bohn Hass Distinguished Professor of Chemistry, Aston Laboratories for Mass Spectrometry, Purdue University, USA, discusses the recent evolution of mass spectrometry, accelerated reactions in microdroplets, and translation issues in healthcare.

What are some of the most significant developments in analytical science over the past 10 years?

The evolution of mass spectrometry (MS), and its continuous growth has been the most significant development. I would also add that the emergence of lipid analytics – especially lipid isomer analysis has also changed the face of analytical science. Spectroscopy, especially imaging, optical methods, and the various 2D, second-order methods have come a long way, and microscopy – carried out with various types of laser spectroscopy – has continually gotten stronger for disease diagnosis applications. I also think that the continuing strength of protein MS and ion mobility spectrometry cannot be ignored. Finally, measuring mass, rather than mass over charge, has advanced hugely in the last 10 years, and expanded our access to high mass complexes.

What are your personal highlights over the last 10 years?

Our most exciting discovery has been the accelerated reactions in microdroplets. This is perhaps as much physical chemistry as it is analytical chemistry, but there are strong implications in analysis and drug discovery. In 2011, it was first reported that organic reactions in microdroplets occur with accelerated rates – up to 106 times quicker than in bulk. This topic has been widely studied since, and more research has been performed on the fundamentals. We use desorption electrospray ionization (DESI), a fully automated system that completes the three main processes of drug discovery – reaction screening, small scale synthesis, and bioassays. This wasn’t on the horizon 10 years ago, and I have been surprised at the speed with which DESI MS is proving useful. Though it is equally surprising how slowly these applications are being translated to point of care medicine!

Why do you think DESI hasn’t been translated into point-of-care medicine more quickly?

In part this is because major advances in genomics have driven interest in genomic and proteomic analysis while there has been much less attention paid to small molecule diagnostics. Moreover, medicine is necessarily slow in adopting new techniques. Translation is also slow in the sector that I am most involved in – brain diagnostics - were we take measurements on microsamples, and provide important information on mutations of the brain tumor that should be of immediate value to surgeons. Currently, this information is available from genomics testing but the information is only available after surgery, when it is not of operational value. Although the relationship between the mass spectrometry and medical communities is really close, one would hope to see many more joint publications between surgeons, pathologists, and experts in MS that address actual medical conditions and patient data.

What lessons has the field learned over the last 10 years?

There has been a slow increase in the realization that, when we handle complex materials, we do not need to separate out all of the individual components. The universal thought used to be that if you have a complex sample, you can’t make a mass spec measurement unless it’s chromatographically cleaned up. That’s just nonsense – but this lesson has taken a long time to learn. It’s not always necessary to separate and purify complex materials to answer questions, including quantitative questions!

How does your most recent paper on the implications of microdroplet chemistry on abiogenesis rank in terms of importance compared with your many other papers?

I do think it’s quite important. Chiral selective research and transfer of chirality (based on serine) was something that I became interested in a number of years ago. We worked on the project for 10 years, and found that the serine octamer can enhance chirality and transfer it to various biological compounds, including other amino acids and sugars.

It could be that all of prebiotic biochemistry, including making peptides, proteins, and nucleotide RNA, is microdroplet chemistry.

I think that accelerated reactions in microdroplets will become a very significant field of science. In terms of what I’ve been able to contribute? Well, my group really did make some amazing first observations. We’ve stuck with the research, and passed some of our enthusiasm to other people by exporting students. Although I’m not entirely satisfied with the progress that we’ve made on the fundamental mechanisms, the contributions that other researchers are making is very pleasing.

Is there anything that worries you as an analytical scientist?

Within chemistry, analytical science is less appreciated than are the other branches. There are historical reasons; consider that, in the 1950s, the field hit a plateau in development of gravimetric and optical methods, which led to some misconceptions about the long-term prospects of the field. Leading institutions responded to this downturn and, as a result, high quality analytical chemistry in the US at least, became quite restricted geographically. To this day, analytical chemistry is rarely viewed on as a major part of chemistry. For example, many university departments combine physical analytical research.

What do you think the next 10 years will look like?

The emergence of mass spectrometry as a synthetic/preparative method will stand out as a further extension of one of the largest and fastest growing areas of analytical science. Examples are collecting products of accelerated reactions in droplets (organics and nanomaterials) and ion soft landing to make new materials.

Any closing comments?

My closing point is to express real appreciation of the analytical community – the people who are in industry, the people who are in academia, and the students who are preparing to go in either of these directions. It’s a great community in terms of the people and the cohesiveness – and I very much look forward to joining my colleagues in welcoming next year’s new graduate students.