A.I.M. Keulemans

Keulemans was a key mentor for me. Through him, I met a lot of people. He would invite anybody involved in chromatography to Eindhoven to work with us. He himself was such a strong scientist – I’d studied his first textbook at Purdue, as well as all of his publications.I’d been in Eindhoven about two or three months, and he said to me, “Harold, you’re doing so well – how much do I pay you?” I was paid nothing – just 300 guilders from a Fulbright scholarship.

He said, “I will double whatever I’m paying you.” I thought, “Great – two times zero.”

Then he said, “I’m going to start you on 700 guilders a month – I’m going to make you a Wetenschappelijk Ambtenaar Eerste Klasse”– which in English means “government worker scientific first class”. I think it probably translates as Assistant Professor.

He said, “You have to teach a course called Unit Operations.”

“I can teach that,” I said.

“It starts next week.”

“I can do that.”

“You’ll need to teach this course in Dutch.” And I did. I think he wanted me to stay in Holland.

He told the students not to speak English to me at all – so you can imagine, after two months I was speaking Dutch. The group consisted of myself and four boys, working together 24 to 36 hours nonstop, sharing jokes – and there was a lot of bad language among the students. Shortly thereafter I was having coffee with Keulemans and he said, “Harold, I have to compliment you. You are good, almost fluent in Dutch, but damn – you sure sound like an Amsterdam sailor!”

Steve Dal Nogare

Steve Dal Nogare was acknowledged as one of the top pioneers in chromatography – he was very enthusiastic about the subject, and introduced me to temperature-programmed GC. Had I not worked with him and realized that temperature programming would be evolving so rapidly, I would really have been somewhat discouraged. Steve also guided me into another important part of my career; before he passed away he told the American Chemical Society, “If I’m not available, please have Harold take over my short courses...” He passed away soon thereafter. I took over ACS GC courses and benefited greatly from them. “Thank you, Steve.” Steve was also a great mentor. When I was working for him back in 1958, I was still a bachelor. I’d been out partying the night before, betting on horses, and chasing girls a little. He said to me, “Harold, here you are in one of the best GC labs in the world, and you’re coming in late every day – you’re wasting my time and yours.” Man, I was destroyed – I felt so bad all morning. About two hours later, he came up to me and said: “Hey Hal, where are we going for lunch?” He basically kicked my butt and then two hours later came and gave me a hug. He had enough respect for his students and colleagues to say, “Here’s where you’re screwing up, but let’s maintain a friendly relationship as well.” I appreciated that – and learned from it.

Denis Desty

Denis Desty was a pioneer, and famous for several reasons. First of all, he chaired the first international GC symposium in London, 1956. He was already recognized by his colleagues in the UK as an expert. He introduced and published a glass-drawing machine, enabling us to move away from the stainless-steel columns, which were far too polar. He had a BS degree in chemistry, starting college in 1940 and then spent several years in the RAF – returning to college after the war and graduating in 1948. He joined British Petroleum, where he spent the rest of his scientific career. When he retired, the Queen of England knighted him for his contribution to the economy of the United Kingdom, for his efforts with BP and petroleum exploration. Once, Denis Desty came to visit us and I took him to the basic research labs of Dutch Shell in Amsterdam. We were sitting in a little hotel, having a nice cup of tea, when he suddenly said, “You know what I remember most about the second world war? All those buzz bombs.” We carried on drinking our tea. He said, “I used to walk round London at night and they were so noisy. One night I was walking around and all of sudden the noise stopped. I thought, ‘Oh no, if the engines have stopped that means they’re coming down’, and sure enough they landed close by us. That was one of my most memorable days – I’m glad I made it through.” I’m thinking, we’re sitting here about to work on capillary columns and he’s talking about buzz bombs. But that was Denis Desty.

Carl Cramers

June 1960 was a great time. Carl Cramers was a third-year student when I was the first postdoctoral fellow. Cramers had a good grounding; prior to coming to university, he already had a four-year diploma from a technical high school, and he knew chemistry, physics and mathematics unbelievably well. We worked as a team, fabricating and testing a flame ionization detector. We also worked on an electron capture detector with Jim Lovelock. One time, Marcel Golay and I made a prep scale column with a four-inch diameter, based on a publication from Germany, but Cramers said it wouldn’t work. I asked why not and he said, “Well have you calculated the lateral diffusion of these samples in the gas phase?” I said, “No, how do you do that?”He said, “Well, it’s a double differential equation, but I’ll show you.”

I never understood that equation. Plus the column didn’t work at all – he was right. When Carl talked to people, he always said, “Harold McNair got married to Marijke but I was the best man at the wedding.” And that’s a true story – he actually was my best man.

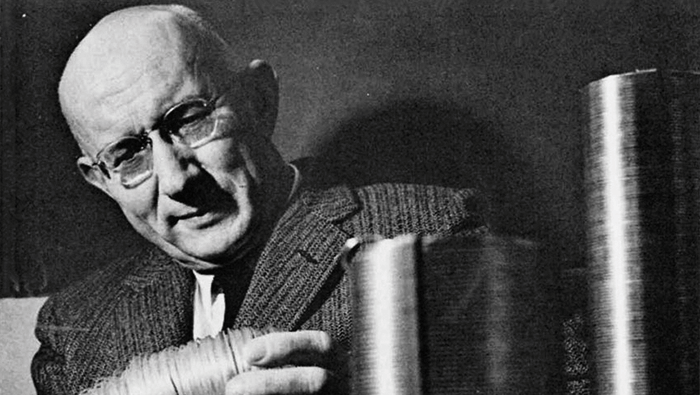

Marcel Golay

In my opinion, Marcel Golay was a real genius. He invented the Golay infrared detector – this was his own, patented design for seeking out and measuring small amounts of heat. It became part of heat-seeking missiles for the US Army. He is known for inventing capillary columns, first introduced in 1957 at PerkinElmer – and a major contribution to GC – but he also developed an algorithm, together with one of his colleagues, Savitzky, used for curve smoothing both GC and LC detector signals. He also had a PhD in Physics from the University of Chicago. Ultimately, he worked as a part-time consultant for PerkinElmer in Connecticut. He said, “I want to demonstrate capillary columns, and I want to find a European wife.” Finding a wife was quite easy... but teaching myself and Carl Cramers how to make capillary columns was a little bit more complicated. The best part about Marcel was how funny and humorous he was. Once we had the columns assembled, Marcel Golay would show us his methods for making capillary columns – and we made many. He filled his capillary with a solution, and then told us we had to seal off one end and evaporate all the solvent out the other end. “How do you do that?” I asked, and he laughed at me and said, “I just put chewing gum on the end!” It turns out, that wasn’t true – he actually used a small torch to melt the glass end to seal it permanently. But he also made the capillary longer than needed, and cut off the first and last two meters. I remember going for supper one night in Eindhoven at a nice bar close to the university. Marcel was fluent in French and English, but didn’t know Dutch. He ordered a Martini, but the bartender gave him a Martini Rossi, which is a very sweet European wine. Marcel took a first sip. “Ooh, that’s terrible,” he said. “Tell the bartender I’m going to make a good Martini!” And he went behind the bar. Of course, the bartender objected. “Sir, please don’t touch him,” I said. “He’s a distinguished professor at the university. I’ll take care of him.” The bartender replied, “Sorry, but I’m going to call the police.” The police arrived and I told them the same story. The policeman said to me, “I tell you what: if the bartender agrees that this gentleman’s Martini is better than the one he gave him, we might let you go.” So Marcel made this Martini, just gin, a drop or two or Vermouth, and an olive. Thank God the Dutch like gin. The bartender said, “Man, that’s a good Martini.” The policeman said, “Young man, tonight you won’t spend the night in jail – but next time, explain to him that he needs to get permission from the bartender first.” Marcel didn’t even know what we were saying.On another night, I took Golay and A.J.P. Martin out to supper. We went to a nice restaurant, but the two of them were arguing like you wouldn’t believe – for about two hours. Finally, at about 9 o’clock, I tried to politely excuse myself to Marcel: “I became engaged to Marijke yesterday and I’m meeting her at the train station for a cup of coffee.” Typical Marcel: “Good idea, bring her here!” I learned early on that you never argue with distinguished professors or Nobel Prize winners – you always lose. So I didn’t say anything, and Marijke and I joined them. Marcel said, “Young lady, I can understand that you might want to get married, raise a family, have children, but... with a damn American?” Marijke said, “Well you obviously don’t know him as well as I do.” Marcel said, “Well I hope not!” After a few minutes of repartee, Marcel says, “Young lady, when you move to New Jersey, and Harold’s working for Esso there in a big refinery, please come by my home in New Jersey, and I will make fondue fromage.” About nine months later we were in New Jersey, having fondue with Marcel Golay.