The Analytical Scientist, in collaboration with LECO Corporation, Restek, Axel Semrau and GL Sciences, invited those working in the GC-MS space to submit their most impressive application notes for the chance to win some exciting prizes – all expenses paid facility or conference trips, consumables worth $3,000, and instrument discounts, to name but a few.

Our expert panel of judges – including Robert K. Nelson, James Harynuk, Susan Richardson, Hans-Gerd Janssen, Giorgia Purcaro, Erich Leitner, Jaap de Zeeuw, and Robert Trengove – have considered the entries and the results are in! Our winners across the following categories are:

- Dmitry Koluntaev for Best Novel Application

- Anika Lokker for Excellence in Chromatography

- Flavio A. Franchina for Creative Use of Application Workflows, Sample Prep & Automation

- Katelynn Perrault – Special Recognition

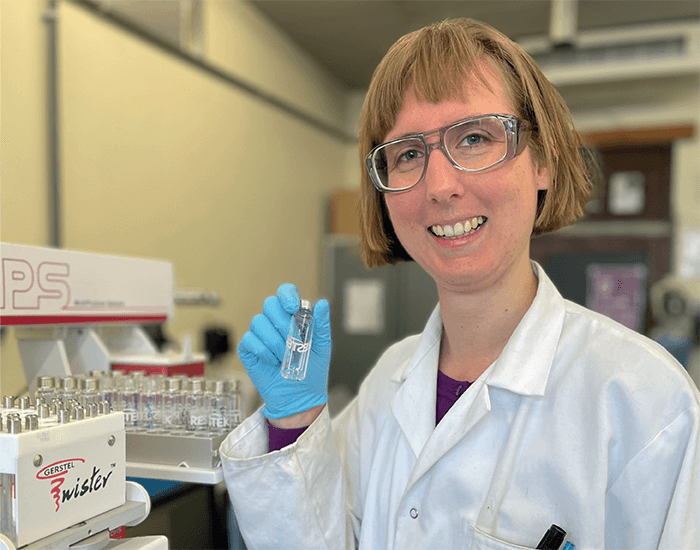

Here, we catch up with Excellence in Chromatography winner Anika Lokker.

With Anika Lokker, PhD student, University of Liège, Belgium

Please introduce yourself…

I am an analytical chemistry PhD student with a heart for archaeological research. From a young age, I was interested in history (archaeology, in particular) and science. Combining both of these areas for my PhD project has been very stimulating.

My PhD project focuses on non-destructive identification of prehistoric adhesives, which could have been used to attach a handle to the tool or as a protective wrapping. Resins, waxes, gums, animal glues, tars, and dry distillation of birch bark might have been used as adhesives in these times. Since the adhesives tend to remain present on stone tools, whereas the organic handle is often gone, the analysis of adhesives is important; it can tell a lot about how the tool was used.

We are currently developing a non-destructive analysis method, using the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) released by the adhesives. VOCs are trapped with dynamic headspace (DHS) before being separated and detected with comprehensive two-dimensional GC-TOFMS (GC×GC-TOFMS). The technique is fully automated with a multipurpose sampler (MPS). The main focus of the project is on artifacts from several excavation sites in South Africa from the Middle to the Late Stone Age (150,000–20,000 years ago).

This project is interdisciplinary, with two groups from different faculties working closely together – the analytical chemistry group of Jef Focant (OBiAChem, Faculty of Sciences, ULiège) and the prehistoric research group of Veerle Rots (Traceolab, Faculty of Human Sciences, ULiège).

Another PhD researcher and a postdoc researcher are working alongside me with a focus on functional analysis of stone tools, which entails technological use-wear and residue analysis. This process involves several non-destructive microscopic and spectroscopic techniques. Together, we are trying to understand the life cycle of stone tools.

How did you become involved with this project?

A few years ago, a proof-of-concept study was conducted in my lab using HS-SPME-GC×GC-TOFMS to identify prehistoric adhesives. I started my PhD project with this technique, too.

However, it soon became clear that HS-SPME is not sensitive enough to detect the VOCs of very old archaeological artifacts. Therefore, I started to look further into different HS techniques options, finding articles in which they compared HS-SPME with DHS. I discovered that DHS has a higher response and sensitivity. With this knowledge, we changed our system to use the potential of DHS and optimized the extraction. This change showcased the measurement of a real archeological artifact and highlighted the working benefits of DHS.

What were the main challenges?

The results were not very promising at the beginning of the study. I was struggling to optimize the method of DHS – it didn’t look much better than HS-SPME in terms of sensitivity. It also took some time to familiarize myself with this method as it wasn’t used much within our lab. It was only after the discovery of the design of experiments concept that I managed to break through this barrier.

What were your main findings?

Using DHS allowed us to detect VOCs from a very old artifact with more success than HS-SPME. We’re only at the beginning of the project, but the results with DHS look very promising in being able to identify the adhesives used on ancient artifacts.

Any lessons learned?

In this line of research, I am constantly learning new things, especially because I just started working with this kind of instrumentation. One thing that I can take forward from this project is to have patience – things will work out eventually if you are determined; troubleshooting (a lot) is part of the job!

Do you have any tips for scientists hoping to bring a touch of creative flair to their application workflows or method development?

It might be obvious, but keep expanding your search for interesting applications – go broader than the intentional field of interest. If you face a problem with the current applications in your research field, try to look for other methods applied to another research field with similar molecules of interest; I took a lot of inspiration from DHS applied to food and beverages research and applied it to archaeology.

What comes next?

I’m currently planning to continue work on my PhD project and dive deeper into what DHS can mean for prehistoric adhesives – we’re just getting started! One thing we are planning to do is look into artificial aging of the adhesives. We expect that fresh adhesives will have a different VOCs profile to aged adhesives, but only time and research will tell.

You can download the application note here.