Bioengineered Humanity

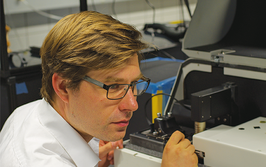

Sitting Down With... Waseem Asghar, winner of the 2016 Humanity in Science Awards and Assistant Professor, Department of Computer & Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, and Biological Sciences, Florida Atlantic University, USA.

Congratulations on winning the 2016 Humanity in Science Award!

Thank you so much. It’s wonderful news – but it will take some time to absorb... I’m certainly very happy and honored to be chosen for such a prestigious award, and it will no doubt push me to work even harder. Such encouragement at any point in one’s career is extremely welcome, and it will provide me with a boost of positive energy for quite some time!

Tell us about the winning project...

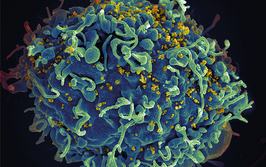

The main focus of my work is developing point-of-care (POC) devices with applications in several diagnostic areas. Our nomination for the Humanity in Science Award fits within that research and describes the development of a transparent, cellulose paper-based microfluidic biosensing platform. The motivating thrust for the project was to develop low cost diagnostics, specifically for HIV viral load and CD4 quantification – but we expanded into detecting other viruses, bacteria and specific cells in blood – all integrated with mobile technology.

Right now, there are about 36 million people infected with HIV, but common diagnostic tools are based on PCR or flow cytometry – expensive instrumentation and expensive tests with a requirement for a state-of-the-art lab. In the developed world, such tests may be perfectly acceptable, but they are not feasible in developing nations – which account for around 75 percent of all those infected.

What inspired the direction you took?

We looked at glucometers – handheld devices facilitating self-management of diabetes – and wanted to replicate the functionality for a broader spectrum of diseases for millions of potential patients. Next, we needed to find the most appropriate materials, all the while focusing on cost and the potential to be locally produced.

Where does your passion for meeting unmet diagnostic needs stem from?

I see people suffering around me and it compels me to act. Going back to diabetes, I have a 19 year-old cousin with the disease who is now managing it well because she can monitor her own glucose levels. My mother also had diabetes for many years, and I remember as a child knowing that she was unsure about administering the correct dose of insulin. An inexpensive portable device has transformed the disease for patients. My work location has a high number of new HIV cases, so I can see a need around me; POC devices in community centers could make a real difference.

Consider Ebola and Zika; one big problem is that the diagnostics are not cheap and simple, which makes disease management almost impossible. And what about the next disease burden around the corner? Simpler detection methods can rapidly be modified for upcoming infections.

What stage is your work at?

We have tested our devices with real clinical samples (blood and serum), and we are now in the process of evaluating the devices with patient samples. The next step will be to move forward with FDA approval. And although our device gives very rapid results (25-30 mins) for viral load in a clinically relevant range, we are also continuing to optimize sensitivity.

How did you come to combine engineering and biology?

When I was a kid, my parents always used to say, “Our Waseem will be an engineer or a scientist,” and, in a way, I think I followed a path partly to fulfill that prophecy! It certainly matched my interests – I loved tinkering with car engines and ‘reverse engineering’...

At first, I wasn’t particularly interested in biomedical engineering until I took one course during my PhD that sent me on a new journey into bioengineering. I worked hard outside of my PhD – I took a lot of extra courses, studied online, and read many books – all to build my knowledge in biology and biochemistry, so that I could succeed in what I felt was my new career direction. A post-doc at Harvard Medical School exposed me to clinical work and challenges – as did another at Stanford Medical School. Now, I am very satisfied; I’m doing what I want to do. I’m helping humanity in some way, and there’s no greater goal.

Which scientists do you respect?

Harvard’s George Whitesides springs to mind first; I really like the work he’s done so far. Langer is another inspirational character. But there are many other people doing great work, such as Samir Iqbal (University of Texas), Utkan Demicri (Stanford University), Mehmet Toner (Harvard Medical School), and Rashid Bashir (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign). Reading their papers keeps me motivated – it’s where I want to see myself.

Winner of the 2016 Humanity in Science Awards and Assistant Professor, Department of Computer & Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, and Biological Sciences, Florida Atlantic University, USA.