Fluorescent Owl Feathers Reveal Age and Sex Markers

Using high-performance liquid chromatography and UV detection, researchers trace how porphyrin pigments vary with age, sex, and body size in owls

| 2 min read | News

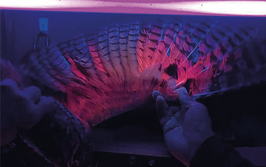

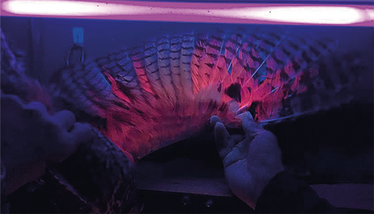

Long-eared Owl wing under ultraviolet light, illuminating the fluorescent pigments visible on the underside of the wing.

Credit: Chris Neri

A new study has provided the most detailed look yet at UV-fluorescent pigments in bird feathers – which can only be seen by humans with the help of ultraviolet light – reporting a strong correlation between fluorescence intensity and physical traits in long-eared owls (Asio otus).

Researchers from Drexel University and Northern Michigan University applied fluorometric and chromatographic techniques to quantify pigment concentrations and assess their variation within a migrating population of owls based in Michigan. Using fluorescence detection via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with a fluorometer, the team measured the presence of porphyrin pigments – primarily coproporphyrin III – in feathers collected from 99 long-eared owls during Spring 2020. These pigments fluoresce pink under ultraviolet light and degrade with sun exposure, a property that field researchers have used for aging owls, but which had not previously been quantified across a large sample.

The team found that adult and female owls displayed the highest concentrations of fluorescent pigments, while juvenile birds and males exhibited significantly lower levels. “Our study shows that female long-eared owls have a much higher concentration of these pigments in their feathers, challenging a common misconception that colorful plumage is a ‘male’ trait,” said Emily Griffith, lead author of the study, in the team’s press release.

Additionally, weight was positively correlated with fluorescence among juvenile and smaller female owls, suggesting a potential size-related saturation point in larger individuals. “This trait doesn't follow a strict binary – the amount of fluorescent pigments in these owls exists on a spectrum where the amount of pigment is related to size, age and sex all together,” Griffith added.

The study relied on a standardized pigment extraction method involving acetonitrile and hydrochloric acid, followed by fluorescence detection at excitation and emission wavelengths of 403 nm and 603 nm, respectively. Quantification was calibrated against a coproporphyrin III standard. Although the function of these pigments remains uncertain, the researchers emphasize the value of analytical tools like fluorometry and chromatography for uncovering hidden traits in avian physiology.

Future work, the authors noted, will be needed to explore pigment degradation over time and to determine whether such fluorescence plays a visual role for the owls themselves. “So little is known about fluorescent pigments in bird feathers and owls aren’t the only ones with fluorescent pigments,” said Griffith. “So, it’s a really exciting time to be interested in studying bird plumage.”