CSI: Dust DNA

Will the future see crime scene investigators collecting nasal swabs or rinses from deceased victims to identify the assailant? In a word: yes.

I remember reading an article called “CSI: Breathprint” by Terence Riley and Joachim Pleil earlier this year. They asked the question, “Will the future see crime scene investigators collecting breath samples from potential perpetrators to identify them?” Their answer was “no”, and I would have to agree. However, Riley and Pleil were focused on the lung. What if instead we focus on the nasal passages? And instead of focusing on the “breathprint” (total lung contents at some snapshot in time), we focus on just one type of particle?

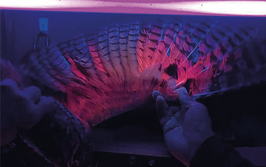

In her book, “The Secret Life of Dust: From the Cosmos to the Kitchen Counter,” Hannah Holmes states, “At least a billion and a half pieces of dust enter your nose and mouth every day, if you breathe exceptionally clean air. Most people inhale many times that number.” Like Pig-Pen (the character in the Peanuts comic strip), we all live within our own personal cloud. Each person sheds around 50 million skin flakes per day, and inhale back into their own body around 700,000 of them. In 1998, Miguel Lorente and colleagues looked at dandruff as a potential source of forensic DNA. They showed that dandruff contained some nucleated cells, and that the DNA could be extracted, multiplied by the PCR reaction, and typed. Although interesting, nothing has been done with this information – after all, at a typical crime scene how could you collect either only dandruff particles from the assailant, or collect everything and then somehow separate out only the dandruff particles from a suspect? It appeared to be a dead end.

People close to each other have overlapping personal clouds. If during the course of a struggle that results in the death of an individual and involves more than just momentary contact between the victim and the assailant, it’s logical to assume that the last few breaths taken by the victim will contain a comparatively high percentage of skin particles originating from the assailant, especially as the dynamic process of air exchange stops at death. Could the nasal passages of the deceased be a relatively rich source of DNA information, the assailant’s ‘dust’ having been trapped by cilia and mucous? And if these skin particles could be recovered via nasal swabs or lavage for example, could enough DNA be recovered, amplified, and typed?

Certainly, the collected sample would still be highly complex, but we could expect that the most abundant source of DNA would be from the victim, followed by skin particles from the assailant. As Na Hu and colleagues note in their review of developments in forensic interpretation of mixed DNA samples, “Over the last decade, the accuracy and repeatability of mixed DNA analyses available to conventional forensic laboratories has greatly advanced in terms of laboratory technology, mathematical models and biostatistical software, generating more accurate, rapid and readily available data for legal proceedings and criminal cases,” but they also recognize many challenges, including stutter, contamination and artifacts of allelic drop-out (4). We’re not quite there just yet.

A more manual alternative method could see individual skin flakes being filtered out of a nasal swab solution and selected for separate DNA typing. You may think that such an approach seems completely impractical, and yet it’s already been tested with adhesive tapings from skin and clothing (5).

How long will it take for the necessary technology to advance to the point where complex DNA analysis becomes cheap, easy and infallible? I can’t say, but I guarantee it will happen far sooner than some ‘experts’ would predict. Do you recall how long experts said it would take to sequence the entire human genome?

- T. Riley and J. Pleil, “CSI: Breathprint”, The Analytical Scientist, tas.txp.to/1214/breathprint

- H. Holmes, “The Secret Life of Dust: From the Cosmos to the Kitchen Counter” (John Wiley & Sons, 2001).

- Miguel Lorente et al., “Dandruff as a Potential Source of DNA in Forensic Casework”, J. Foren sic Sci. 43(4), 901-902 (1998).

- N. Hu et al., “Current Developments in Forensic Interpretation of Mixed DNA Samples”, Biomed. Rep. 2 (3), 309-316 (2014).

- H. Schneider et al., “Hot Flakes in Cold Cases”, Int. J. Legal Med. 125, 543–548 (2011),

Over thirty years in forensic science have taken Bob Blackledge all over the world to testify as an expert witness or to attend international conferences. “I feel extremely fortunate to have worked in an area where, every day, I looked forward to going to work and facing new challenges.” Bob says that the term “Forensic Scientist” is very broad (and detractors might even say it’s an oxymoron), so he describes himself as “an analytical chemist who specializes in forensic science.” Although his interests are actually very broad, Bob’s special love is trace evidence. He is the editor of “Forensic Analysis on the Cutting Edge: New Methods of Trace Evidence Analysis” (Wiley Interscience, 2007.)