Casting A Wider Net

When fighting food fraud, there are problems that analytical science alone cannot solve. We must work together to take a more inclusive and multidisciplinary approach that ensures true food integrity.

Petter Olsen |

The psychologist, Maslow, visualized a hierarchy of needs as a pyramid, using it to describe a method of problem solving – starting at the bottom and gradually working your way to the top, using known methods. However, this doesn’t include the “real” analysis of the problem. In 1966, he also said, “When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail,” indicating that not all problems can be fixed with one tool.

Ditching the golden hammer

As an analytical scientist, you may sometimes be tempted to use this “one tool” approach – especially when you’ve worked hard to try and establish a method; unfortunately, using it makes you biased, whether intentionally or not. You will look at a problem and choose your favorite method to try and solve it – perhaps because you’ve used it before, or because it’s undervalued or unused and you really need to prove its relevance to those who put the problem to you in the first place – after all, you’ve invested a lot of time, effort and money in its development.

Clearly, such thinking isn’t limited to analytical scientists. I come from information technology and computer science, with information logistics being my specialty. I am well aware that computer scientists have their favorite programming languages and typically want to use them, even if there are approaches that are more suitable for the job.

What if we place this narrow thinking into the context of food fraud? We’re reading more and more reports these days about how organized crime is playing a greater role. Of course, there is an important role for analytical science in tackling the problem, but simply selecting an analytical approach because that’s the way it’s always been done before is not a solution.

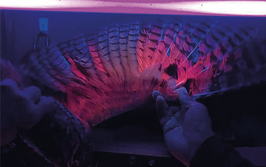

Why is seafood a special case?

- Seafood is traded internationally more than any other foodstuff: often seafood is processed and then traded

- More than 1700 species of fish are traded internationally

- For many species of fish, there is no internationally agreed upon commercial name; the same name is used in different countries to refer to completely different species

- Seafood is a valuable commodity with great potential for economic differentiation between species and products

- Between 14 percent and 33 percent of captured fish (FAO estimate) is from illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fisheries, and fraudulent claims related to origin routinely occur to enable this fish to enter the normal and legal supply chain and be sold there

- There is great concern relating to sustainability of many fish stocks; sustainability claims are valuable

- Seafood is in the Top Three wrongly described foodstuffs

Source: Petter Olsen 04/11/15 ©NofimaMarket

Food safety and food security in some contexts are identical, whereas with food fraud you are looking for something that indicates that there is a biochemical property of the food that can be detected analytically. Therefore, there is a need to enhance analytical methods to enable more testing – investing in techniques that are cheaper and faster.

Food fraud is an issue that crosses country borders; therefore, we need to be able to replicate methods readily, so that we are able to identify instances where the country of origin has been changed intentionally or where there is over-production in areas that have strict quotas. There is also the issue of economic fraud, where producers claim that food comes from one country or area, but – to avoid tax or sustainability problems – it’s being produced elsewhere. All of these are huge problems that analytical science by itself cannot solve. For example, I am not aware of any analytical methods that can detect whether slave or child labor has been involved, or whether workers are paid on time – both of which are classic indicators for social sustainability.

Essentially – if we focus on the food safety issue only, then we are missing a big part of the problem. We need to look at it as a whole and analyze it before deciding the next steps; we all need to be reminded to revisit what we’re being asked to do so that we can find a complete solution. For example, it may be that we are being told that there is a major problem with meat fraud within the retail market. We need to start at the top of that pyramid, looking at it in great detail, and then work our way down gradually to decide on the different methods that will help with the analysis. Analytical scientists can only be expected to analyze the samples they have in front of them. They can’t be everywhere at once. On the other hand, if you track “paper trails” you may discover that in reality there should only be 100 tons of a certain food product in the supply chain, but there appears to be 200 tons. That would clearly indicate fraud…which should help with obtaining samples for biochemical analysis, for example. By taking this approach we will identify what we can do – and crucially, those areas where we need to involve others with different competencies. Again, we need to go back and address the problem, not begin with the methods.

Fish in a bigger pond

There is most certainly a need to involve economics in the solution. Chris Elliott (Queen’s University, Belfast), speaking at the Recent Advances in Food Analysis (RAFA) conference in Prague, reported that food safety has been forgotten and is underfunded – something which is hitting those laboratories that have invested heavily in methods and technology and are not as active as they once were.

Each year, the EU defines a number of societal challenges for food, and each challenge will receive between one and ten million Euros. For 2016, the catalog contains about 90 challenges. But these project awards are not simply to fund science itself; the EU is looking for answers to the whole problem of food fraud and that means involving all kinds of people, including analytical scientists, information logisticians like myself, economists, socio-economists, and so on. Working as a multidisciplinary team, we can find the underlying cause of why the fraud happens, how it happens, and how it impacts the economy.

I understand the EU project funding system well. During RAFA, I presented our food integrity project, which I believe is the biggest of its type and has the clear multidisciplinary approach the EU looks for when awarding projects and funding. Over the last 20 years, I’ve been working within international projects and I think that what the EU expects makes sense. Of course, the EU does fund science through the European Research Council, for example, but those projects are not on the same scale. In the larger “societal challenge” projects, the EU recognizes that science is necessary… but also that it is only part of the solution.

Seafood fraud in Brussels

- 380 seafood samples taken in restaurants in Brussels

- 15 percent of these from EC and EP restaurants

- 32 percent total mislabeling (wrong species)

- Not Bluefin tuna – 95 percent

- Not cod – 13 percent

- Not sole – 11 percent

- Pangasius common

Source: Oceana Report, 3/11/15

With my own institution – NOFIMA – we have two economics departments, both of which contain socio-economists. They have identified that virtually all EU projects now have an economic and a socio-economic component. It didn’t used to be the case. Current projects are all moving away from the narrow, targeted analytical science approach to work that paints a bigger picture and provides answers to food fraud problems on a broader scale – which may involve social sustainability, eco-labeling, and so on. Clearly we need to involve specialists from many more areas, with analytical (and other) scientists creating technological solutions as part of the overall package.

During my experiences of working on EU food fraud projects, I have found that if I get involved early on in the discussions, the consortia members are almost exclusively analytical scientists. I then have to stand up to say we can’t just do science, and that we need to bring in people who understand stakeholder engagement. We need to co-create the solution with the industries we expect to put it to use. We need to engage them, discover what their motivations are. Only then can we get their precise requirements and feedback – and involve them in implementing the solution to the societal challenge.

If we develop a new method or instrument, we need the industry to understand how it will benefit from using it – as opposed to continuing with old equipment or approaches. It can be difficult (even after going through cost–benefit calculations) to convince people that they need to change; again this calls upon other specialists within the project team. The same strategy can be mirrored in many other areas.

Imagine we have a problem with species mislabeling. We could take the ten best DNA analysis labs in Europe and ask them to do some profiling. Then we could add a couple of economists to figure out the economic impact. But once again, it would be the wrong way around. We’d be beginning with the method again and not really addressing the bigger problem being raised by the EU, which brings us back to my main message: start by analyzing the problem and not narrowly focusing on the method(s) you want to use because you feel they’ll give you a result.

Bigger fish to fry

Working for NOFIMA entails working with food projects in a more general sense. Norway may be a small country but when it comes to fish, we are a world leader. That includes fish caught by our fishing fleets and those produced in aquaculture. We are important exporters of seafood to the world’s markets, and we import everything else we need other than fish. In fact, seafood is one of the most internationally traded foodstuffs. And that means we need a lot of knowledge about food supply chains and food fraud, safety and security. You may not be surprised to learn that Japan is one of the biggest consumers of Norwegian-sourced fish – and that makes the supply chain long and complicated. We need to know precisely what is going on along the way (and it also means I need to do a lot of traveling).

We’ve even incorporated “citizen science” into a food integrity project. Miguel Angel Pardo at AZTI (a marine and food research center) in Spain oversees this. Anyone can join in by contacting Miguel ([email protected]) and he will send you ten sample tubes for collecting small pieces of fish claimed to be a particular species. Each time you decide to claim something is cod, tuna or some other species of fish, you just need to place a small piece of the fish into the tube and send it to his group for analysis. He then translates the findings into a map showing whether the fish was genuine – a green dot – or fraudulent – a red dot – onto a map of Europe, giving a view of the distribution of the problem and adding to the bigger picture. Again, we come back to this analysis being part of the overall solution we are working towards and not the whole answer.

Similar studies have been conducted by the research organization, Oceana (see Seafood Fraud in Brussels). In November 2015, following DNA testing by KU Leuven, Oceana discovered that about 30 percent of seafood served in restaurants in Brussels did not correspond to the species ordered by the consumer.

Based on Petter Olsen’s presentation at RAFA 2015 and a subsequent interview.

Petter Olsen is senior scientist at Nofima, Tromsoe, Norway, where he has worked since 1993. He works with applications of ICT in the food industry, especially related to information logistics, product documentation, environmental accounting and traceability. He has also been an advisor to many organizations on traceability-related subjects, including the European Commission, WWF and the Nordic Industrial Fund.